Montreal’s Irish Community Clings to What’s Left of Its Heritage

In Light of Griffintown’s REM Station, the Irish Want Commemoration

Last November, during work on Pointe-Saint-Charles’ light rail station, the remains of about 15 Irish immigrants fleeing the Great Famine were dug up by archeologists surveying the site.

In 1847, about 6,000 Irish people seeking refuge died of typhus and other ailments and were buried in mass graves. The approximate site of these graves is marked by a three-metre tall stone named the Black Rock—spitting distance from where the remains were dug up. Workers building the Victoria Bridge erected the inscribed boulder, the world’s oldest Irish famine memorial, in 1859.

Considering its importance, the memorial is relatively unknown. Irish-Montreal historian, teacher, and tour guide Donovan King described it as “largely inaccessible […] on a tiny traffic island, straddling two highways in an unsightly industrial zone. Gaudy advertisements on giant billboards glare down on the boulder, which is encircled by a wrought iron fence.”

But, in January, Mayor Valerie Plante was reported to have expressed openness to the idea of rerouting part of Bridge St. for a proposed memorial park to honour Montreal’s Irish famine victims.

Kevin Tracey of the United Irish Society said Montreal’s Irish are the only community who fled the Great Famine lacking an appropriate place of remembrance.

“Our goal as the city is to make sure that the Black Rock is in a place that will be easily accessible, because right now it is absolutely not accessible,” Plante was quoted as saying in the Montreal Gazette.

Still, many feel Montreal’s Irish community doesn’t have proper commemoration as most of its heritage sites in the city are ruins. For example, the St. Anne Church in the historically Irish neighbourhood of Griffintown was torn down, and only its foundation remains in Griffintown Park.

“We’re looking at mostly ruins, and even the ruins are being destroyed,” said King. St. Bridget’s Refuge, which has been turned into a park where a pavilion will be built, is another example, he said.

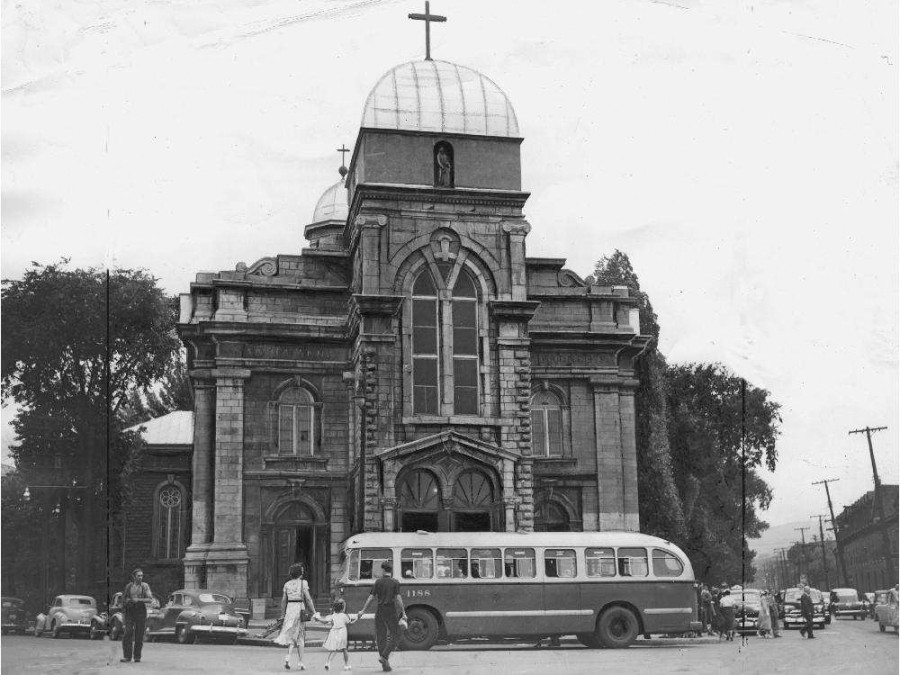

The Saint Patrick’s Basilica is the only one that’s intact, he said. “It’s really sad. We have a family cemetery by the Lachine Canal that’s not marked at all. That one’s already been dug up in the 1870s to make a basin, but we believe there’s still parts left. So there’s really no proper commemoration.”

The Réseau express métropolitain, which is extending its light rail trackage, is building a station in Griffintown—and its proposed name has caused much controversy. Back in November, Plante tweeted a proposal to name the station in honor of former premier Bernard Landry. “The Griffintown-Bernard-Landry station would recognize Mr. Landry’s important contribution to the development of our city, in the middle of the Cité du Multimédia, which has become the symbol of the bold economic vision of our former premier,” she tweeted.

There was an immediate outcry from the Irish community, who feel the Griffintown station should have a name that pays homage to its history, especially since the former premier had a history of berating immigrants and Indigenous people.

After the failed 1995 referendum, Landry was reported by the Montreal Gazette, in a story picked up by the New York Times, to have yelled at two employees of the InterContinental hotel that it was “because of you immigrants that the ‘no’ won,” adding, “Why is it that we open the doors to this country so you can vote ‘no’ [to Quebec sovereignty]?”

In an open letter to the mayor, King said, “Given that Montreal’s Irish immigrants built Griffintown from the ground up, including the Lachine Canal and Victoria Bridge, many feel that it is wrong to name the REM station after a controversial and divisive politician.”

King stresses that the city should honour this history and name the station out of respect for the Irish who “built the Griff from the ground up” and lie buried by the thousands in its proximity.

While giving his tours, King has noticed people want to hear the stories and feel connected to their ancestors. Pointing to the gentrification of Griffintown, he said so much of Montreal’s Irish heritage has been destroyed. “We just want to preserve the little bit that’s left and actually enhance it,” he said.

Tracey said there are many names the Irish community would be happy with. Some have proposed the station be called St. Patrick’s or Des Irlandais. Others would like to name it after the 1847 mayor of Montreal, John Easton Mills, who died of typhus while tending to the sick. Most, however, would simply be content with the name Griffintown.

“This happened right around the time they were digging up the remains of our ancestors and quite a few of those were skeletons of children,” said King. “This is a period of mourning we are in, until they’re reinterred at least. It adds insult to injury.”

A previous version of this article stated that the Black Rock monument is three feet tall. It is in fact three metres tall. The Link regrets this error.