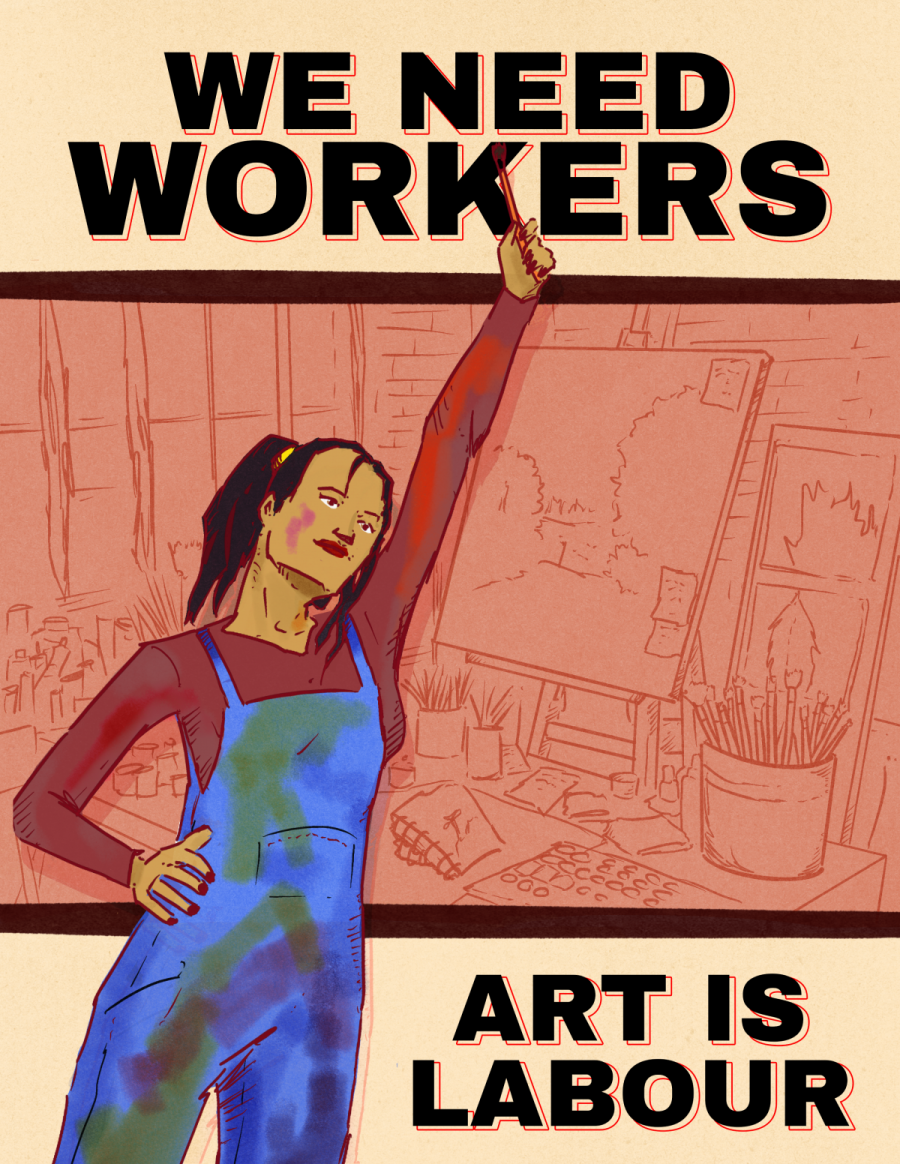

Art is labour

Three Montreal artists speak on routine, instability and the work behind the work

Long before performance or product, there are hours spent warming up bodies, answering emails, planning schedules and holding together work that doesn’t end when the creative part does.

The demand for artistic labour is shaped as much by circumstance and time as by talent. And it doesn’t look the same across disciplines.

For multidisciplinary visual artist Poline Harbali, labour takes a quieter, more continuous form, structured around routine, solitude and sustained focus.

Harbali’s days often begin outside. She describes physical activity and time spent walking as essential to her process, a way of grounding herself before settling into work.

“The experience of nature, of being in relation to nature, of being able to go outside,” Harbali said, explaining that time outdoors is not separate from her practice, but part of it.

Unlike artists whose schedules shift daily, Harbali approaches her work with a structured approach. She views her artistic practice explicitly as labour.

“I really see my artistic work as work,” Harbali said, “I have a schedule, I have a fairly rigid work routine.”

The work, she explained, takes up most of her time, leaving little room for other commitments, especially with her recent decision to return to school.

Making a living as an artist, however, remains difficult. Harbali draws much of her work directly from her own life, a reality she described as both generative and stressful.

“A large part of my work is very closely tied to my life. It creates a certain stress to see how much life experience is tied to earning a living,” Harbali said.

“Tour sounds glamorous,” Solomon said, “but I don’t have roadies. I don’t have an assistant planning it for me. It’s just me sending emails.”

Despite the intensity of her schedule, Harbali does not frame her practice as a source of burnout. While long production periods often lead to fatigue, she described that exhaustion as cyclical rather than harmful.

“It isn’t related to artistic work,” Harbali said. “On the contrary, it’s a place of joy, security and pleasure.”

Whereas Harbali organizes her labour around routine and sustained focus, poet Misha Solomon describes a practice shaped by fragmentation. He doesn’t follow a daily writing schedule, and his work rarely unfolds in a predictable rhythm.

Instead, writing happens between freelance contracts, academic responsibilities and the administrative labour that comes with publishing. Solomon explained that he does most of his writing “for a specific purpose,” whether for a course, a writing group, or a prompt he has set for himself, rather than as part of a fixed daily practice.

That lack of routine doesn’t mean the work is casual. Much of Solomon’s labour takes place away from the page entirely. Preparing for his upcoming book tour meant weeks of organizing logistics on his own, from coordinating with bookstores to reaching out to poets in other cities.

“Tour sounds glamorous,” Solomon said, “but I don’t have roadies. I don’t have an assistant planning it for me. It’s just me sending emails.”

That behind-the-scenes work, he noted, is rarely visible to audiences and rarely compensated. Payment for poetry itself remains inconsistent.

“Most journals do pay something, but that can be as little as $20 for a poem,” Solomon said.

As a result, Solomon supplements his practice through freelancing, teaching workshops, and academic work.

Even when people take his work seriously, Solomon is cautious about its framing. He acknowledges how lucky he is to be in a community with poets and scholars who take it seriously as a pursuit. However, he resists calling poetry a job outright.

“A job has a lot of connotations,” Solomon said, explaining that he feels less comfortable applying that language to his work.

What matters more to Solomon is the recognition of the practice as deliberate and sustained, rather than dismissed as something fleeting or ornamental. Recognition may validate the work, but it does little to ease the instability that often surrounds it.

Where Solomon hesitates to call poetry a job, trumpeter Rafael Salazar is explicit about what music requires. He laments that people rarely see or value the labour that makes that entertainment possible.

Salazar, a recent graduate of McGill University’s jazz performance program, described his days as physically and administratively demanding long before a gig ever begins. His mornings start with breathwork, not the instrument itself.

“Without breath, we don’t have vibration," Salazar said. "We can’t create without the breath."

Before touching the trumpet, he spends time preparing his body, emptying his mind and going through what he calls a maintenance routine, where the exercises are not creative but necessary. That routine alone can take over an hour.

“That’s just maintenance,” Salazar said. “It’s not practicing music or anything at all.”

Only after that does he move into actual musical work: learning repertoire, composing or preparing for upcoming gigs. On days with performances, he avoids additional practice altogether to preserve his body.

What looks like a three-hour set onstage often amounts to six or more hours of labour. Salazar counts warm-up time, the gig itself and commuting as part of the workday.

“That’s without counting listening to music,” he added, noting that music remains a constant presence even outside active practice.

Much of that labour happens offstage and unpaid. Booking gigs, coordinating musicians, sending emails, tracking payments and following up on late transfers make up a part of the job.

Salazar described waiting weeks to receive payment for multiple performances, money that affects not only him but the other musicians relying on that income.

Late-night performances create additional costs.

Many gigs end after public transit has stopped running, forcing musicians to pay for expensive rides home. After factoring in preparation, travel and administrative work, Salazar recalled a time when all that was left after additional costs was around $90 for an entire night.

For Salazar, the issue is not simply low pay, but the perception of musicians.

“People don’t see the business behind the art form,” Salazar said.

If they did, he believes they would recognize musicians as workers providing a service.

Because of this, Salazar is deliberate about how he presents himself to venues. He insists on contracts, clear rates and professional boundaries.

Respect, he explained, often comes before the music itself, through how a musician negotiates, communicates and asserts their value.

At the same time, Salazar is critical of how low pay has become normalized within the industry. When musicians accept poorly paid gigs or undercut standard rates, he argued, it drags wages down for everyone.

“People will play for peanuts,” Salazar said.

Across disciplines, the labour looks different, but the impulse to continue is shared. For Harbali, Solomon and Salazar, the work persists not because of its stability or reward, but because stepping away is rarely an option.

Despite the physical toll, long hours and financial instability that shape their days, none of the artists describe their work as something they could simply give up.

As Salazar put it, “I have no choice. I feel it in my blood and my veins.”

With files from Sarah Housley and Ryan Pyke.

This article originally appeared in Volume 46, Issue 8, published January 27, 2026.

_1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)