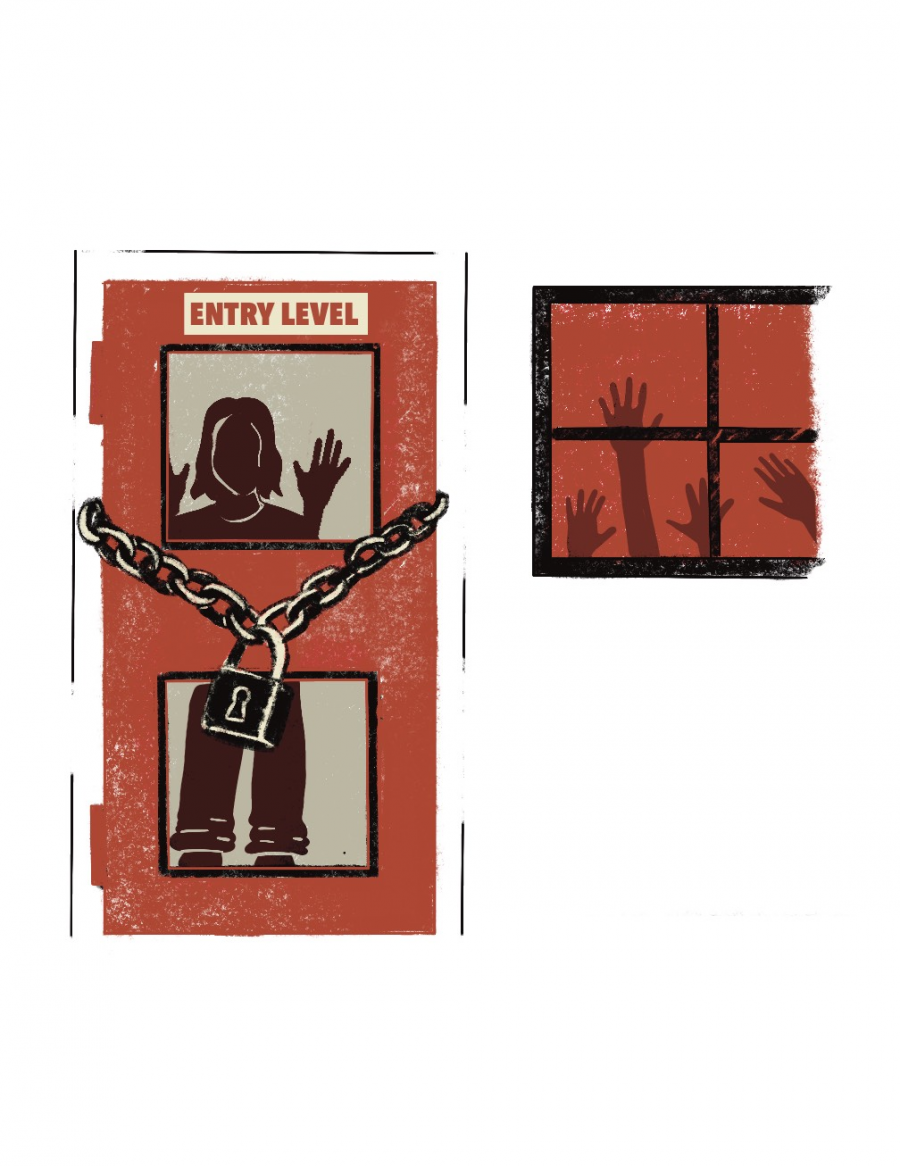

The vanishing doorway to work

Why “entry-level” jobs no longer exist

In a past that already feels foreign to most students, “entry-level” meant opportunity. It was a first step, not a final hurdle. Today, the term often means “already experienced, still underpaid.”

Scroll through any job board, and you will find junior or assistant roles asking for two to three years of experience, advanced technical skills and professional connections that most newcomers simply do not have.

For many recent graduates, the “entry” part has quietly vanished from “entry-level.”

The result is a strange contradiction in the job market: companies complain about a shortage of talent, yet new workers cannot get hired because they lack experience.

Employers increasingly want candidates who can hit the ground running, with little to no training. Tight budgets and cost-cutting have sharpened that expectation, with unpaid internships and short-term contracts replacing the kind of full-time roles where people used to learn as they went.

A recent study by Business Insider found that 69 per cent of jobs labelled “entry-level” now require three-plus years of previous experience, especially in fields like marketing, communications and technology.

Meanwhile, the cost of living continues to rise, making unpaid work a luxury not everyone can afford. For anyone without financial support, long internships are simply unrealistic, filtering out talented people from low-income or marginalized backgrounds before they even have a chance.

A career ladder that used to feel straightforward now feels gated.

More and more, employers have placed less value on mentorship and training, pushing the responsibility for skill development onto individuals and universities.

Yet, higher education cannot prepare students for everything. You can teach theory, tools and technical basics, but you can’t simulate the workplace: the pace, the expectations, the politics, the mistakes. Skills like collaboration, adaptability and professional judgment only come from doing the job.

When companies refuse to invest in new workers, they don’t just block young professionals from entering the labour market; they undermine the pipeline they’ll later claim is “empty.”

Fixing entry-level work isn’t complicated, but it does require honesty.

Employers need to stop seeing training as a burden and start viewing it as a long-term investment. Paid apprenticeships, clear development programs and honest job descriptions are realistic steps that can benefit both workers and companies.

Governments also have leverage here, through incentives for businesses that hire and train early-career employees, and through tighter standards around what “entry-level” is allowed to mean in the first place.

If employers want a future workforce, they need to build the bridge instead of demanding that newcomers arrive fully formed on the other side.

This article originally appeared in Volume 46, Issue 8, published January 27, 2026.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)