Are immigrant workers being left behind?

Closures of accelerated residency pathways have complicated access to work for many immigrants in Montreal

In the bustling neighbourhood of Cotes-des-Neiges—Montreal’s largest borough, known for its vibrant community of immigrants from different backgrounds—lies an essential service.

The Immigrant Workers Centre (IWC) provides legal information to some of the most vulnerable workers in Quebec.

According to Fatima Beydoun, a case worker who conducts intake evaluations for the IWC, some people take long commutes from outside the Greater Montreal Area just to access the services. These include workers' rights education and help mobilizing around issues that can arise in the workplaces such as accidents, harassment and unpaid wages.

“Most people come from places where they sold everything before coming,” Beydoun said.

Accessing immigration brokers or lawyers to help complete permits or residency applications can cost hundreds of dollars. For example, Toronto law firm Matkowsky Immigration Law charges $250 for a 30-minute consultation and $8,000 for refugee claims as well as hearings.

“When applying to any permit, it feels like you’re putting all of your documents in a bottle and throwing it into the ocean, because there’s no feedback until you get a yes or a no.” — Azul Gonzalez, public health researcher

For Azul Gonzalez, a public health researcher who immigrated from Mexico to Montreal in 2021, dealing with permits and immigration bureaucracy has been a difficult part of their integration.

Last November, after paying $300 for a consultation with a lawyer, they began their application for the Programme Experience Quebec (PEQ). The PEQ is an accelerated immigration program meant to target foreign workers and students who graduated from a Quebec institution.

It was scrapped last November, and its sudden closure has left Gonzales searching for other avenues.

“When applying to any permit, it feels like you're putting all of your documents in a bottle and throwing it into the ocean, because there's no feedback until you get a yes or a no,” Gonzalez said.

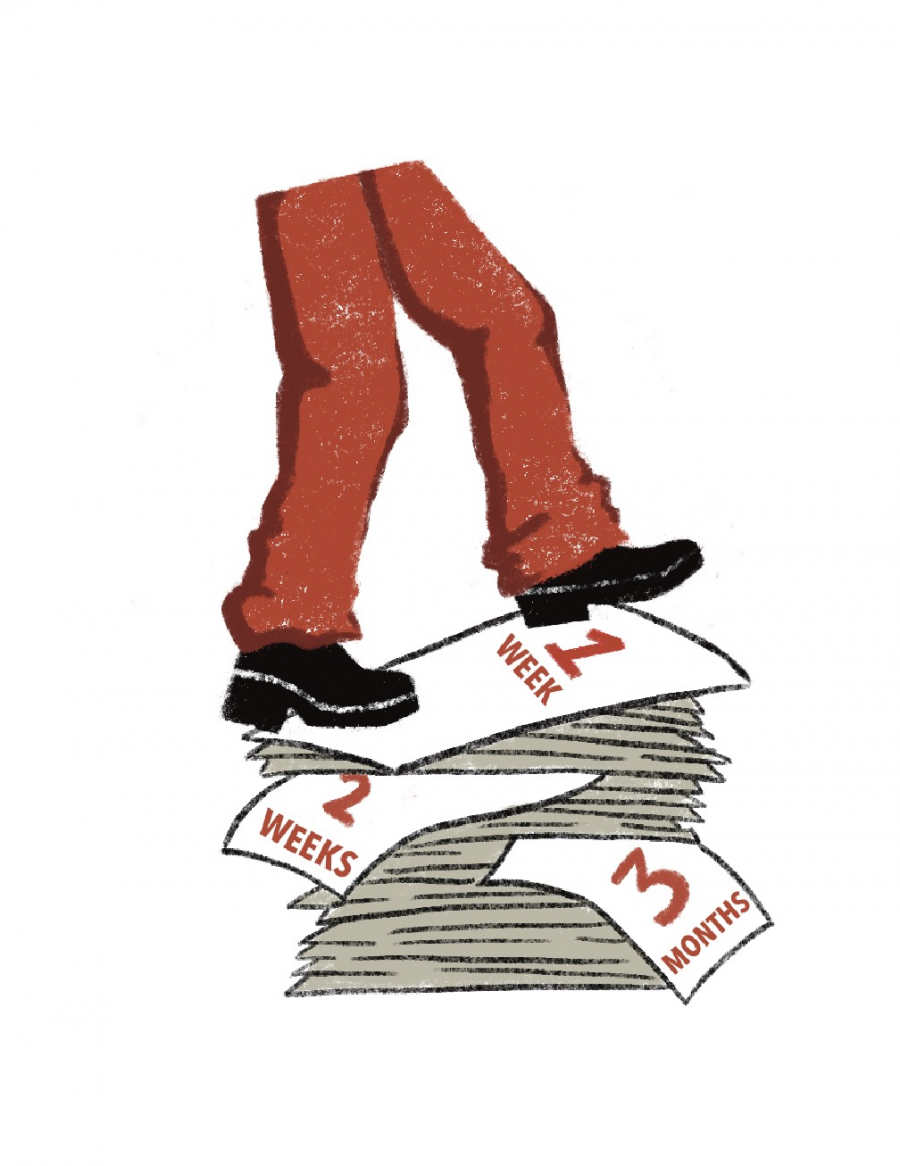

Newcomers to Canada can be stuck in “bureaucratic limbos” according to Émile Baril, a postdoctoral fellow at Concordia University’s Institute for Research on Migration and Society.

“If your application is delayed,” Baril said, “some people can wait up for like 14 months, and they still need an income.”

Gig work organized through digital platforms is flexible, and while it can give autonomy to workers, it is not always transparent with its pay structure. A majority of the time, Uber drivers, for example, are offered different wages for the same trip as determined by an algorithm. It is unclear what factors are at fault for the discrepancies, as reported by The Globe and Mail.

“Unsafe environments for work are not just physically unsafe. Usually, there’s harassment that’s also paired with it, or you can have a very apathetic employer who dangles your work permit like a carrot.” — Fatima Beydoun, IWC case worker

“Platform labour in Toronto and Montreal is built on a large pool of largely racialized young immigrant workers needing to make ends meet,” Baril outlined in his September 2025 research on food couriers in Canada’s major metropolitan cities, including Montreal.

Recruitment agencies also charge thousands of dollars to place migrants in domestic or warehouse work, which are both environments prone to workplace abuses, according to Beydoun. Domestic workers, the majority of whom are women, are more likely to face sexualized violence and to be pressured into working longer hours that aren’t properly compensated, she said.

The IWC Women’s Committee published a study last December revealing that 42 per cent of women without status in Quebec have faced sexual harassment in their workplace.

Warehouse workers, on the other hand, tend to be subject to unsafe environments and a lack of safety training in an environment where injuries are quite common. Over 80 per cent of Dollarama warehouse employees surveyed by IWC in 2019 reported excruciating back pain.

These conditions put workers at a disadvantage, especially when they possess a closed work permit, which ties their status in Canada to a specific employer.

“Unsafe environments for work are not just physically unsafe,” Beydoun said. “Usually, there's harassment that's also paired with it, or you can have a very apathetic employer who dangles your work permit like a carrot.”

Assia Malinova, a community organizer at IWC, primarily works with warehouse or factory employees.

Malinova says it can be intimidating for workers to report abuse or malpractices at work when they’re not familiar with what resources they can access. These include services offered by the Commission des normes, de l'équité, de la santé et de la sécurité du travail (CNESST), Quebec's government body that manages employment standards, pay equity and workplace health and safety.

“We have a lot of workers that come here, people who have recently arrived in Canada, who don't know what the CNESST is,” Malinova said. “They don't speak the language, they cannot understand what rights are broken, so we help them identify, and we have to also help them make the claim.”

Budget cuts imposed by the provincial government at the CNESST in 2025 further aggravated delays for workers seeking justice. Scapegoating by politicians and challenges of securing a permanent status in Canada contribute to the precarity of immigrant workers, according to Beydoun.

“We need to invest in communities and in housing," Beydoun said, "instead of scapegoating immigrants for the incompetencies of the government."

This article originally appeared in Volume 46, Issue 8, published January 27, 2026.