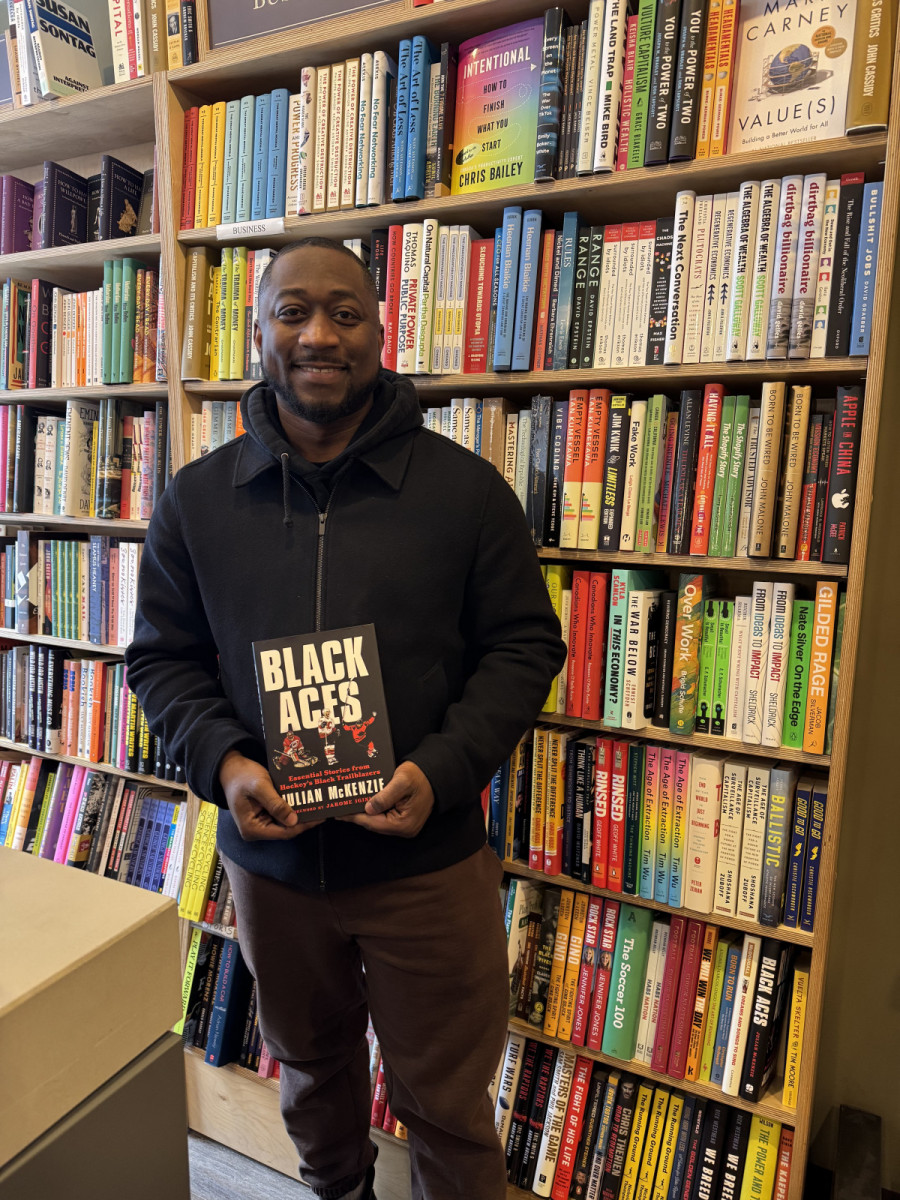

Concordia graduate and former Link sports editor releases new book

The Athletic’s Julian McKenzie sits down with The Link

Julian McKenzie graduated from Concordia University in 2016. Since then, he’s embarked on a tear across Canadian media, with experience at CTV News, the Montreal Gazette and most recently The Athletic.

On Feb. 3, McKenzie released his latest book, Black Aces: Essential Stories from Hockey's Black Trailblazers. The book profiles black players across generations, from Willie O’Ree to Grant Fuhr to P.K. Subban, and unpacks the culture surrounding historic black competition in the NHL and beyond.

The Link sat down with McKenzie to discuss the book.

Disclaimer: Answers have been edited for clarity.

Can you talk to me about how this book started to come together? When did you start to think about putting together a compilation of all these stories?

I want to say mid to late 2023. Around that time, I was approached with an opportunity to write a book by a literary agent that I'm working with now, Brian Wood, and I tried to think of different ideas that would make sense. And then one day, I was in the shower trying to think of different ideas and then the idea came to write a compilation of Black hockey stories and profiles.

And just from then on I approached a couple people about it and my agent and I were shipping the idea, and Triumph Books—it was so gracious of them to accept our pitch—they eventually accepted. And then the next February after I was first approached, we kind of put pen to paper on that and then it was official that it was going to happen, and then we went from there.

I've heard you talk a little bit about how there had been assorted stories of Black players in hockey throughout history, but the rising numbers in both men's and women's leagues facilitated a real place to collect them all together. What is that feeling like knowing that there's a real collection of stories now that makes this a regular occurrence and not just a one-off situation?

It's a cool situation. It shows that, as much as we can look at hockey and say it's a pretty white sport, throughout the years, there's been a rise in more people of colour who have played the sport and have played extremely well to contribute to some big moments in the sport’s history. So to be able to tell those stories in a project like this is really special. I know there are other colleagues of mine, whether at The Athletic or around the NHL, who could easily have done this. So it's not lost on me that I had the privilege of being able to do that.

But yeah, I'm also just happy at the fact that, like someone like a P.K. Subban, or Kevin Weekes or Sarah Nurse, who’s at the Olympics now with Team Canada, to be in a position where we can look at those players and we don't have to look too far in history to see what they were able to do. It's a cool feeling, just like being a hockey fan, to be able to write these stories.

I wanted to talk to you about a few of the players you profiled, starting with the person who opens the book, Willie O'Ree. There's a passage where Grant Fuhr talks about how fortunate he was to have played in a place like Edmonton, where he was so accepted, and that he really got to reap the benefits of the players like O’Ree that came before him. How fitting was it for you to have that first chapter of the book be about O’Ree, the first player to break the NHL's colour barrier?

It just made sense to have him start. There was a point in the project where I thought about focusing on more recent players. But then, as I went along with the process, it just made more sense to put together a proper chapter on Willie O’Ree as opposed to just mentioning him here or there. I had gotten a lot from the event I went to in Edmonton, where Willie O'Ree was commissioned with a stamp. And people like Grant Fuhr and Anson Carter and Georges Laraque were there too, Sarah Nurse, and they spoke very eloquently of Willie O'Ree. It just made sense to start with that chapter and detail parts of his life.

And I get it—a lot of people know who Willie O'Ree is, and he has his own book that details his story. But it is still important that the current generation and generations to come continue to know who he is, who he was as a player, and the fact that he broke the Black collar barrier. And as much time has passed since it happened, 1958, when you really think about it, is still less than 100 years ago. It's not that far off. So it was really important to be able to write about that and tell that story. And I'm glad I ended up writing a chapter on him in the end.

Similarly, you make a point of talking about the players who came before O’Ree and paved the way for his success. What was it like to tell the stories of the players who could have been O’Ree, the players who maybe should have been O’Ree but never got the chance because of the time period?

It was important to get that right. It's obviously easy to just focus on Willie O’Ree, but there are other players who got signed to contracts and ultimately didn't get to play in the NHL. And then, of course, there's Herb Carnegie, for whom you could make an argument that his chapter could have gone first. He played on an all-Black line that was considered the Black Aces. But to be able to tell Herb’s story—how do I want to phrase this?—it's an important story to tell. Willie O'Ree, everyone knows that he did it, and it's a success story, essentially, and it paves the way for so many other people to play hockey.

But for Herb, who didn't get that same opportunity, who doesn't have that same level of recognition, but people eventually caught on, and then they get him into the Hockey Hall of Fame, I still thought that was a worthwhile story to tell, considering his legacy and the work that his daughter's done through the Carnegie Initiative, for example. I just thought he was an important figure to mention. It was important to mention as many people as I could who tried to play in the NHL or play in the league, or even stuff like the Colored Hockey League of the Maritimes, which had all these innovations that came before the NHL existed. It was important to highlight those things.

I'd be remiss if I didn't mention P.K. Subban—obviously a Montreal hero, someone we remember fondly for his passion and his energy. I think some people sadly misconstrued that passion as arrogance. You see players like that across sports, but it's often Black players who receive that label of being 'flashy.' Can you talk a little bit about what it meant to see someone play like that with no real inhibitions about changing his personality or being something he wasn't?

When I grew up in Montreal and watched him play, he was just cool. He was different from everybody else. It was also cool to see people who I wouldn't necessarily think of as everyday hockey fans turn on the TV and watch P.K. because it was cool to see someone who looked so different from the establishment and felt like themselves when they were on the ice. And it was also fascinating to see how certain people looked like they would embrace it.

And then you have other people, particularly management for the Canadiens, just the way they handled their relationship with him, it certainly looked like they didn't—I want to make sure I phrase this right—they didn't embrace him in the same way as fans did or certain teammates might have. Talking to people like Daniel Brière, for example—he comes to mind because I know for sure I spoke to him about P.K. There were guys in that room who actually liked what P.K. provided, particularly in big moments on the ice. And in a market like Montreal, you could have the skillset of a P.K. Subban or even the skillset of a Dale Weise, but if you show up in the biggest moments when they matter, you will be regarded as a legend.

And for P.K. to be himself while also having moments throughout his career as a Montreal Canadiens player that you can go back to and say, “Wow, this made the hair on my neck stand up, this is a big moment, and he delivered.” He played all those minutes in a Game 7, and even if he didn't get a point, he was still the best defenceman on the ice, or he came out of the penalty box and scored a big goal or scored a hat trick in a regular season game.

There are all these moments you can look at and be like, “Wow, he wasn't just a Black hockey player who's cool to look at. He was a guy who delivered when it mattered.” That was someone who, when I was a fan of a team and I watched P.K., was a cool player to look at. A lot of people felt that way about him, too.

Talk to me a little bit about Black women in hockey. You have a chapter on Angela James, another one on Sarah Nurse and Blake Bolden, all incredibly talented players, some of whom are still being underrated and not receiving the visibility that they should. How important was it to magnify the experiences of Black women in hockey just as much as the experiences in the NHL, and now, seeing the PWHL and its rise, how women's hockey and Black women's hockey have grown alongside that?

Just like how it would be difficult to make a project like Black Aces and not have Willie O'Ree, it would be difficult to put together that project and not highlight some of the women who've played well. And it's not even a complete list—I don't even have a chapter on Sophie Jaques or Saroya Tinker. But it was still important to have the players I had in there, whether they're Canadian or American.

Even Laila Edwards, who doesn't have a full chapter in there—she's in the Blake Bolden chapter—and she just made history playing for Team USA at the Olympics. When you look at the rise of women's hockey and see that female players are at the centre is an amazing accomplishment. It goes to show the rise in diversity in the sport. And there's still a lot of work that needs to be done, but I do think that it's really special to see women in these places of prominence when you look at women's hockey.

There's an excerpt in that chapter about Blake Bolden where she talks about a young fan coming up to her and telling her, “You are the reason I play hockey.” What does it mean, not just for the players, but also for you to hear that and know that hockey is changing and that these players are role models to so many young people who are interested in the game?

That's cool. There are so many things with hockey when you look at hockey culture, accessibility, that ultimately need to change in order to maintain its viability. But at its core, it's a great sport to watch on the ice. Particularly in the country we live in, it's a uniting factor for so many people because of how much we appreciate the sport. And even for Blake Bolden, who's in the States, even if the States don't appreciate hockey the same way that Canadians do, there are still people who appreciate it very passionately.

And for someone to go up to Blake and just tell her, “Hey, I look at you as a hero,” I know that, for that particular story, that resonated a lot with Blake. And then it leads to Blake trying to start a good mentorship program for young women and reaching out to different women around the country who want to be just like her; it means a lot. It's massive. And as long as there are role models like Blake and Sarah, you will see more people who will want to be like them, and then you'll see the number of role models continue to multiply.

I feel like it's impossible to choose—there's no really objective best chapter from the book. But if there was one player that you wanted every single hockey fan to know their story, whose chapter would you have them read?

Good question. I think Duante’ Abercrombie's story is pretty crazy. The dude is trying to make his own dream happen. He ends up at some camp in Oakville, and he's training alongside Connor McDavid. He goes to New Zealand to play professionally. He ends up coaching with Graeme Townshend and working at camps, and then working his way onto different teams. And now he's in charge of an HBCU (historically Black colleges and universities) program that hopefully will get off the ground later in the fall. That's a pretty cool story. I think people should tap into Duante’.

Blake Bolden—I enjoyed telling her story, too. She delivers newspapers with her mom and her grandmother, and then just by chance, her mom meets a security guard, and she ends up getting into hockey that way because she's going to games at the local arena. And then she eventually starts her own journey into hockey. Sarah Nurse, obviously.

Tony McKegney should get some shine, too. I don't think I've praised them enough throughout this whole experience, because we look at a guy like Jarome Iginla, who is a power forward but also scored so many goals. Tony McKegney’s not exactly the same player, but at a time when Black players were few and far between, between Val James, who comes in around the same time, and Mike Marson, they're thought of as fighters and role players. In the case of Bill Riley, I think, is the other player I'm trying to think of.

But Tony McKegney established himself as a goal scorer. And that's a really cool thing to see among Black hockey players, especially now, where it's not as much of a thing where if a Black player enters the league, it's like, “Oh, he has to be a fighter.” They can play a different number of roles. So, yeah, I think Tony's someone people should read about. I don't know if anyone's ever really asked me about that chapter, but the dude was involved in the Good Friday Massacre, even though he didn't fight anyone. But that story of him with Van Halen in the locker room after the fact is hilarious. I think it's funny. But yeah, I hope people tap into those chapters.

I was at the Corey Cup last night (Concordia vs. McGill), and I was waiting outside the locker room to get interviews with Coach Marc-André Elément. And this young Black player is waiting on the side, and he’s watching players like Chris Ennis, Xavier Laurent and Igor Mburanumwe walking off the ice. How do moments like that show how far hockey has come, not just at the professional level, but at the collegiate level, and while we have so much space to keep going forward, that there has already been so much work done and that there's so much to celebrate at the moment?

It's cool to be able to celebrate. I just hope that we continue to—I say “we” as in just people in the culture of the sport—we continue to make hockey as inclusive and accessible as we can make it, particularly for diverse groups, for people of colour, whether that's having programs or initiatives that lower the cost of entry or just showing that you can see yourself in the crowd watching games and knowing that it's not an experience that's just limited to one type of person. It's cool to go to a hockey game and see people who look like you, and they're enjoying the sport too.

I think of people like Renee Hess, who started the Black Girl Hockey Club, and they bring together a group of women to go to games. That's cool—you want more of

that there. I see people who worry so much about the culture of the game, and they're all like, “Oh, well, we don't want any of that NBA stuff here,” or whatever. There's nothing wrong with embracing diversity for the sport, because the more people who enjoy it, the better it's gonna be for everybody who enjoys hockey. It shouldn't just be the sport that's gatekept for one particular type of person. So I think anything where diversity shows itself in hockey is a really cool thing.

To close things up, there's the line from Jon Cooper after playing the first all-Black line in an NHL game about how maybe today that's a story, but in the future it's commonplace and not the outlier anymore. Maybe not written by you, but what would a sequel to Black Aces look like? Would you want it to be a similar celebration to this, or would you want it to be just another book about Black heroes and the stories that they've told? Hopefully, by that point, it's a commonplace thing to see more Black players on the ice.

Why wouldn't it be written by me? [Laughs.] I don't have a problem with it continuing to be a celebration of that. There will be more players, there will be more stories, and it will be a mix of young and old. Presumably, you'd want stories from newer players, but also you'd want stories of someone like Mike Marson, like I mentioned earlier, older players that weren't mentioned, or Donald Brashear, if you want. I would imagine Black Aces just being a good combination of what's already worked for the first one. So that's what I think would happen.

Black Aces: Essential Stories from Hockey's Black Trailblazers is available at select stores and online.