What Is No Platforming, and Why Do We Need to Do It?

No platforming is a simple yet controversial concept.

It asks that the public consider the power of speech and presence, and realistically evaluate the appeal of oppressive ideas.

The term “no platforming” extends to a range of strategies that seek to deny oppressive figures and groups access to public discourse, media, and space.

The prevailing public opinion is that toxic ideas like the ones entertained by fascists, neo-nazis, and racists will be weeded out through reasoned debate. This strategy, unfortunately, has proven again and again to be flawed at best, and actively counterproductive at worst. It is a cruel view of history to ignore the bravery and work of those who opposed repressive political forces and social movements by pretending that they simply failed to engage in debate with their opponents.

Why won’t hearing them out work?

When extreme racists like Richard Spencer are given public space, they inevitably make converts. It’s a mistake to think that figures like these are merely misguided. Certain classes profit from their agenda at the expense of the rest. The far-right isn’t riddled with a problem of ignorance, but with a lack of compassion and sense of justice.

Speakers who dog-whistle to the far-right’s agenda also inevitably benefit from it. Jordan Peterson’s appeal to far-right groups is well documented—he makes more than $60,000 a month from crowdfunding. Figures that appeal to the far-right and their agenda, as well as the groups themselves, have very little incentive to change their views and are unlikely to change their minds when confronted with the sheer absurdity and violence of their beliefs. Giving figures and groups more media attention not only fails as a strategy to combat them, but actively contributes to their power and celebrity.

I can understand not letting neo-nazis speak, but why are so-called “alt-light” figures being targeted?

Those who critique no platforming as a strategy tend to ignore the degree to which far-right groups, public figures, and populist movements enable, legitimize, and work in concert with each other, even when deep ideological rifts divide them.

Groups like La Meute and Storm Alliance present a more rhetorically acceptable façade, but it’s one that nevertheless empowers smaller and more overtly violent groups like the Soldiers of Odin and Atalante, despite significant tensions and attempts to distance themselves from each other. It is no surprise that they could be seen marching with each other in Quebec City on Nov. 25, 2017 in opposition of the upcoming Forum Validating Diversity and the Fight Against Discrimination—a one day forum organized by the provincial government to address racism and discrimination in Quebec’s workforce.

Far-right groups all strive to further marginalize, scapegoat, and punish already-oppressed members of society by denying their basic humanity. The degree of sophistication of their language changes nothing to the basic brutality of this worldview.

When either of these large groups takes the streets, members of smaller, more extreme groups tend to follow suit. The larger groups also serve as the ideal base for radicalization and recruitment. Their popular appeal also follows this basic pattern: a “lighter” version of their rhetoric is presented openly to the media, while in private their arguments border on the genocidal through their social media profiles and among each other.

Members of groups that present themselves as “concerned about immigration” like Storm Alliance and La Meute have openly stated their admiration for Hitler, and joked about putting immigrants in gas chambers. Academics and radio personalities can also play a key role in granting legitimacy to fascist discourse, and also represent an important element in this web of radicalization.

Shouldn’t we try and understand the far-right to better combat it?

One of the key aspects to these groups’ appeal is that they draw on existing systems of oppression; they reinforce and thrive on conveniently available narratives.

La Meute’s entire framing of Québécois oppression can only seem palatable or even tenable because of the systematic erasure of the province’s colonial, imperial, and racist history. Anti-fascism should only be considered the tip of the iceberg for addressing systemic injustice, but the far-right’s increased visibility is also an extension and consequence of existing social problems.

It’s especially frustrating that prominent media outlets continue to present the far-right as if it was an essentially mysterious problem. Of course, it’s abundantly clear that there is nothing particularly novel or fascinating about various far-right groups’ belief systems. They all strive to further marginalize, scapegoat, and punish already-oppressed members of society by denying their basic humanity. The degree of sophistication of their language changes nothing to the basic brutality of this worldview.

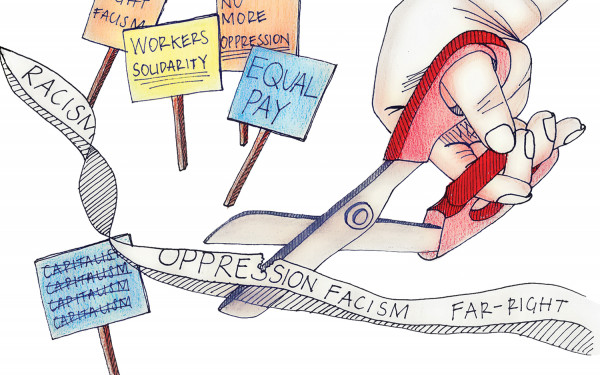

What does no platforming mean in practice?

No platforming extends to the streets, online, and in print. These ideologies need to be combatted wherever they can take root. Traditional platforms include speaking events and demonstrations. Increasingly, however, the new far-right’s recruitment strategy has expanded to online platforms. It’s therefore vital to understand that the basic principles of no platforming should extend beyond its historical applications.

Journalists must also take an active role in denying fascists platforms. While this does not mean that they should stop reporting on the rise of the far-right, it should involve an ethical commitment to never allow them to shape their own narratives.

Beyond activist circles, everyone should be concerned with the rise of the far-right and extreme racism, and actively challenge and combat it whenever it manifests itself in their daily lives. While no platforming in and of itself is vital to the anti-fascist movement, it cannot work unless we also foster alternatives to the far-right’s appeal.

We must build stronger communities of resistance and commit ourselves more deeply to addressing social injustice.