The hidden politics of learning

Cognitive inequality is the unspoken policy of higher education

Every semester begins the same way: a classroom full of students who appear to be starting on equal footing. Same syllabus. Same deadlines. Same expectations.

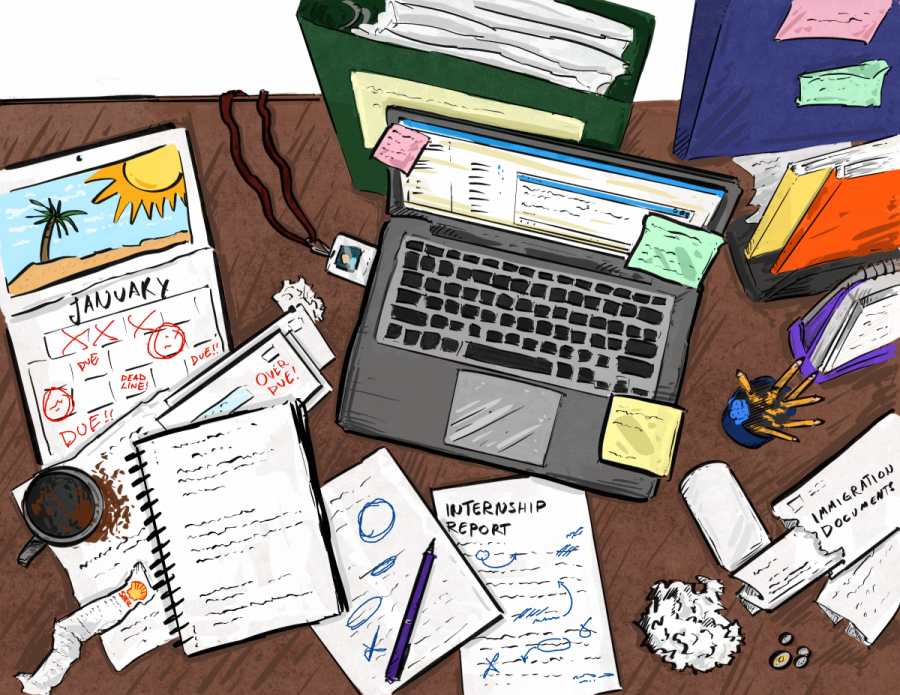

But beneath that surface is a reality universities rarely confront: students do not arrive with equal mental space. Some walk in with clarity and calm. Others arrive carrying the weight of rent hikes, immigration deadlines, identity vigilance or the exhaustion of working until midnight the night before.

We treat learning as if it begins when the lecture starts. But learning begins with bandwidth, and bandwidth is political.

Cognitive science makes this impossible to ignore.

Chronic stress reduces working memory. Financial scarcity creates a “tunnelling effect” that narrows long-term planning and deep focus. Identity threat, whether from racism, sexism, homophobia or linguistic policing, forces the brain into constant vigilance, burning the same mental resources needed for learning. Meanwhile, psychological safety is strongly linked to creativity, risk-taking and retention.

A mind under threat doesn’t fail because it lacks discipline. It fails because the system demands excellence under conditions it helped create.

Montreal’s political landscape shows how uneven this bandwidth can become.

Housing insecurity alone reshapes learning conditions. With rent prices accelerating far faster than student incomes, many now compete for overpriced, overcrowded or unsafe housing. An unstable living situation does not just affect comfort; it drains the cognitive capacity needed for reading, writing and concentration.

When students don’t know if they can afford next month’s rent, studying for a midterm becomes secondary, not because they don’t care, but because biology demands survival first.

Federal budget decisions tighten the bandwidth gap even further. The federal government's Budget 2025 quietly signals cuts to the Canada Student Grant, a change buried deep in the budget tables. For low and middle-income students, reduced grants don’t just mean higher debt. They mean more work hours, more scarcity, more stress and less mental space left for learning.

But money isn’t the only thing draining students’ mental bandwidth in our city.

Identity pressures also reshape the mind’s capacity to learn. Bill 96 has intensified linguistic self-monitoring for Indigenous, immigrant and multilingual students. What should be an ordinary conversation becomes an exercise in vigilance, not fluency, a quiet but constant drain on cognitive resources.

Women, trans and non-binary students navigate another dimension of vigilance, facing higher rates of harassment and dismissal, especially in STEM programs. Safety concerns shape where they study, how late they stay and whether they speak up at all.

Cognitive inequality is not just a Montreal problem; it is a worldwide political ecosystem.

UNESCO data consistently links socioeconomic instability, trauma and gender inequality to reduced learning outcomes internationally.

But cities still make choices. Our own city has the capacity to narrow this gap—or to widen it.

Montreal is not just a case study of cognitive inequality. It is a test of whether universities and governments are willing to design learning environments that protect mental bandwidth rather than quietly consume it.

Universities love to position education as the great equalizer. But equalizers only work when the starting conditions are equal. A student can be brilliant, disciplined and ambitious, but without mental space, none of that is visible.

Cognitive inequality is the silent curriculum of modern education.

Learning is political because thinking requires safety, stability and room to breathe. Until we build systems that protect the mind as much as the classroom, education won’t reveal who is capable. It will reveal who had enough bandwidth to survive the conditions around them.

This article originally appeared in Volume 46, Issue 7, published January 13, 2026.