The first-past-the-post voting system is failing Canadians

Adopting mixed-member proportional representation is the reform Canada needs to protect democracy from radicalism

Enacting a mixed-member proportional representation (MMP) system in Canada has become crucial for accurately reflecting diverse political opinions and safeguarding society against extremism.

In the 2025 Canadian federal election, the Green Party and the New Democratic Party (NDP) suffered a disastrous decline. The Green Party gained only one seat, despite their widespread recognition of climate change. The NDP secured only seven seats. It had won 25 seats in the 2021 election, and lost its official party status for the first time since 1993.

However, the Conservatives gained 144 seats, 25 more than in the previous mandate. Meanwhile, the Liberals won 169 seats and maintained their position as the governing party.

As such, this outcome must reflect strategic voting driven by Canada’s current first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system.

Under the FPTP system, voters can only back one candidate in their riding, and the candidate with the most votes takes the seat in Parliament. As a result, this discourages Canadian voters from supporting candidates from smaller parties seen as less likely to win.

This system has not only accelerated political polarization, but also served as a tool for entrenching a mutually antagonistic relationship between the two major parties—the Liberals and the Conservatives.

The Canadian Parliament must take this issue seriously, especially now that Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre has returned to the Parliament after winning the August byelection. Under his leadership, the Conservatives have absorbed extreme-right votes by promoting anti-immigrant sentiment and reviving trickle-down rhetoric.

In a system like Canada’s, where two major parties are consistently overrepresented in Parliament, the radicalization of even one of them poses a serious threat to democracy itself.

Former NDP leader Tom Mulcair, speaking just a month before the 2025 election, warned that the threat posed by U.S. President Donald Trump and Poilievre might push New Democrats and Greens to vote Liberal. His prediction became reality: many progressive voters set aside their core values simply to block what they saw as the greater evil.

The most significant issue with the FPTP system lies in the fact that every ballot cast for a losing candidate is wasted, undermining the very principle of vote equality.

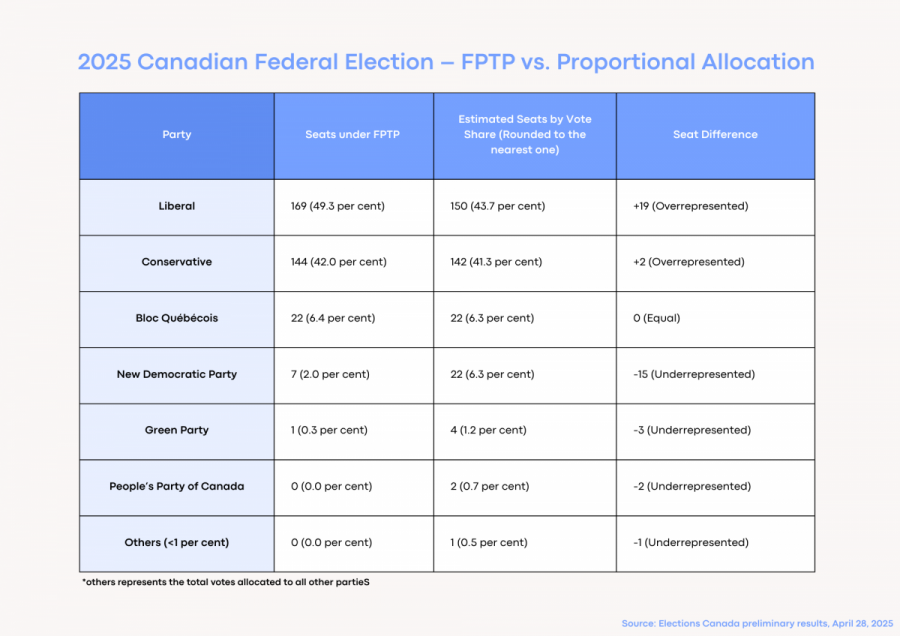

The 2025 election made this clear. The Liberals won 5.5 per cent more seats than their popular vote, yet the Conservatives gained 0.7 per cent more seats, while the NDP took 4.3 per cent fewer seats than their actual share of the popular vote.

In the last four federal elections, from 2011 to 2021, the winning parties—the Liberals and the Conservatives—secured between 13.4 per cent and 14.9 per cent more seats, while the NDP received approximately 6 per cent fewer seats than its share of the popular vote.

Adopting a mixed-member proportional (MMP) system with an additional ballot for party votes ensures that every vote carries equal weight.

Unlike the FPTP system, the MMP system guarantees that parliamentary seats are allocated based on vote shares. Even if your local candidate loses, your party’s vote still counts toward your party’s total seats. As a result, this system reduces wasted votes in constituency races and reflects the full spectrum of political opinion more accurately in parliamentary seats.

Imagine if proportional representation had secured even one-third of the Canadian parliamentary seats: the NDP and Green Party could exert real influence, amplifying social democratic and environmentally sustainable policies that directly benefit voters.

In proportional systems, outright majorities are rare. Coalition governments become the norm, forcing parties to negotiate and compromise. Countries like Germany and Belgium show how these dynamics can work to democracy’s advantage, building alliances across parties while using a ‘cordon sanitaire’ or “firewall” to isolate extremist movements and prevent them from dictating policy.

Conversations about adopting MMP can’t wait until the next election cycle. Electoral reform won’t just fix a broken system; it can protect Canadian democracy from polarization, advance better governance and contain extremist forces before they can reshape society.