Invisible No More

A New Indigenous Women’s Bike Collective Takes to the Streets for Visibility

Plastic strings and colourful glow-in-the-dark beads are scattered across a table outside Concordia’s EV building.

Three students enjoy an arts and crafts session in the sun at the FOFA Garden as they bead strings—one goes over to her bike and ties a beaded string to its frame. Their mission for the afternoon is to bejewel their bikes and make themselves “Indi-Visible.”

“We were talking about being indigenous in the city and how biking is really a mode [of transportation] that we’ve used to mobilize,” said Camille Usher, an indigenous student who studies art history, and a member of the Indigenous Art Research Group at Concordia.

“Bikes have really helped with our personal freedom and empowerment, and they move us to a place we want to be,” she said.

The use of glow-in-the-dark beads plays on the idea of visibility as urban indigenous women.

“When we’re biking around it’s a way of making the roads indigenous and taking space,” said Isabella-Rose Weetaluktuk, an indigenous filmmaker raised in Nunavik.

Crafting a Place for Themselves

According to Dr. Karl Hele, professor and director of First Peoples Studies at Concordia, there are endless reasons why indigenous students may feel unwelcomed at the university.

Over the last decade or so of teaching, Hele said some of the comments he has been privy to about indigenous students are often examples of blatant and systematic racism, ongoing colonialism, and a large deal of ignorance.

“Being aware of the fact that we’re on unceded Mohawk land is not something you get through [being at] the university. I wouldn’t have known if I hadn’t taken certain classes. There just needs to be more awareness,” said Usher.

“The difference is we’re not recognized in our own country,” said Cedar Eve Peters, an indigenous art history student who was selling her handmade beaded jewelry outside at the FOFA Gardens. “We’re the only people in the world who have to prove our identity with a status card. If someone says they’re German, then they’re German. You don’t question it,” she said.

When receiving comments about being lucky for not having to pay taxes, Peters said she just wishes her family didn’t have to go through a great deal of suffering to get that in the first place.

“It’s not that one minority suffers more than the other, it’s that we’re not even recognized in our own country,” said Peters. “That’s what I think is really messed up.”

Moreover, indigenous students are often away from their home and culture, and that Montreal and the university are foreign to them—a factor that many might not realize.

“There are a limited number of indigenous students, making you feel alone in class or on campus,” said Hele.

“I feel like it’s really hard to be in an institution that’s not very welcoming. There’s not a lot that’s directed towards our success. I didn’t really feel welcome here and I still don’t because there’s not a lot of funding for indigenous people,” said Usher.

Hele echoes that there is indeed a lack of indigenous faculty and staff and support in departments and faculty.

“It comes down to money and space [which is] something universities seem to be loath to part with in great amounts when it comes to indigenous peoples,” said Hele.

The problem may be stemming from a national academic standpoint. When looking at Canada’s school system as a whole, Hele expressed that there is not enough in being done to educate students on native history or current affairs from kindergarten to university.

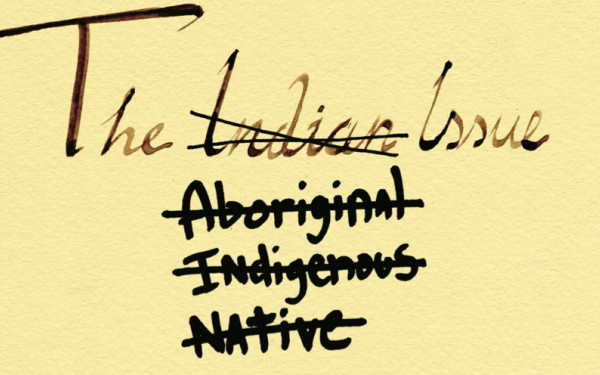

“There are few to no courses relating to indigenous peoples, a lack of readings and materials by indigenous authors, and the course content usually makes them not appear at all, briefly, or as social problems,” said Hele. “Course content on indigenous peoples that is wrong, […] or stereotypical fails to capture the idea that we are not all ‘issues’.”

“We’re the only people in the world who have to prove our identity with a status card. If someone says they’re German, then they’re German. You don’t question it.” – Cedar Eve Peters.

Biking for Visibility

The bike beading was inspired by a documentary involving a group of indigenous women called the Ovarian Psychos who established a bike collective in L.A.

“They got together and started biking around the city raising visibility for the fact that they’re indigenous and still present. We care about where we live and we still want to find ourselves and our identity in our landscapes,” said Cheli Nighttraveller, a Cree Concordia student originally from Saskatoon who also studies art history and is a member of IARG.

These three bike beaders are the founding members of the Uppity NDNs, an all-indigenous women’s biking collective. According to Usher, they are using biking as a methodology to decolonize space, spike conversations and inspire creative production.

This year will be the first time that IARG will be organized entirely by indigenous people without directors or any sort of hierarchy.

“Our idea for this year is to focus on conversations that need to happen at the moment,” said Usher.

Their events last year, according to Usher, were planned in academic settings with panels and conferences. This year, however, they wanted conversations to happen in a friendly space, without any constraints.

“We want to give everyone an opportunity to say things, and get a bit messy, and be able to make mistakes,” said Weetaluktuk. The three women are making it clear that they want to hold events that are open, which will give anyone the opportunity to join in and talk a bit.

The collective described the event as an opportunity to educate people on issues that affect indigenous communities, from an indigenous point of view.

“It would be really fun if we did lots of bike rides on the full moon where we invite everyone who would like to join in, find more people to bike with us,” said Weetaluktuk. “Make the streets feel a bit more friendly.”

1web_900_601_90.jpg)

2web_900_589_90.jpg)

_600_832_s.png)

ED1(WEB)_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)