Idle No More Protest Retraces History in Montreal Streets

Protest Route Maps Shared Native and Non-Native Landmarks

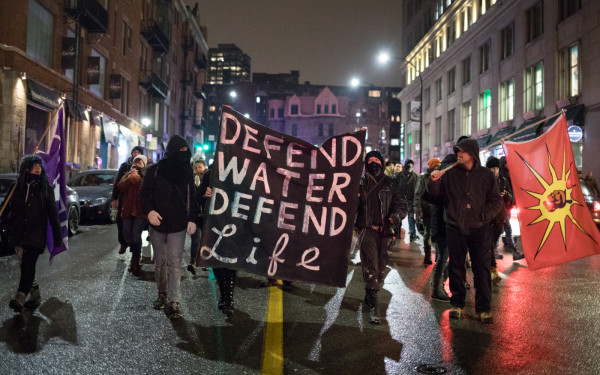

An all-ages group of demonstrators supporting the Idle No More movement weaved through downtown Montreal by the dozens Sunday afternoon.

Sporting familiar red feathers, hand drums and rattles, the protest—which included families of small children and both native and non-native supporters—was largely peaceful and devoid of the police confrontation that erupted at other demonstrations in the city this weekend.

“The important thing is to make people notice we’re not finished with our actions,” said Idle No More Quebec founder Melissa Molin Dupuis.

The protest marked the 250th anniversary of the signing of Treaty of Paris, which recognized native treaty rights to land when it outlined France’s forfeiting of its North American territories to England.

Calling it more of a “walk” than a demonstration, Dupuis said retracing history was the major focus of the event.

“During our walk we’re going to stop at different attraction points for economical exchange between First Nations and non-natives,” she explained.

The march began at Philip Square, across from the Bay on Ste. Catherine St. W. in downtown Montreal. The Hudson’s Bay Company was chosen as a starting point since it began as a Crown corporation, trading fur with the native population.

Other landmarks on the route included the Palais de Congrès, which was home to the Salon des ressources naturelles this weekend, a forum on employment to support the Plan Nord natural resource development project in northern Quebec.

Though falling just after demonstrations against the multi-billion dollar project, which saw 36 arrests on Saturday alone, the coincidence was unintentional, according to Dupuis.

Since it began last Fall, Idle No More has evolved from a teaching platform of four Saskatchewan women on native rights into a heterogeneous movement encompassing flash mobs, teach-ins, road protests and rail blockades.

The grassroots initiative made national headlines after Theresa Spence, chief of the Attawapiskat nation, began a fast in support of the movement.

Spence’s 44-day hunger strike demanded a meeting between Aboriginal leaders, political leaders and Crown representatives, which was realized on Jan. 11 when delegates from the Assembly of First Nations sat down with Prime Minister Stephen Harper and other officials.

But Idle No More needs to continue the discussion, according to Dupuis.

“It’s going to be a lot of talking to each other,” said Dupuis. “Native and non-native are not even talking—400 years here [together] and we didn’t even get to start talking.

“One of the scariest things for the government is that we start talking and understanding each other.”

1_900_587_90.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)