Concordia, Canada, and the Climate

“Where’s the problem for energy in Canada?” asked 2014 Nobel prizewinner in physics, professor Hiroshi Amano from Nagoya University. This was a complex question. “For me, there seems to be no problem,” he continued.

Sitting in a conference on the other side of the world, I looked around and none of the students, Canadian or Japanese, raised their hand to answer. Yet, what surprised me most was that, for outsiders, there seemed to be no “energy problem” in Canada.

I was at the Japan-Canada Academic Consortium on Energy and Society hosted by Nagoya University, which was held for a week in February.

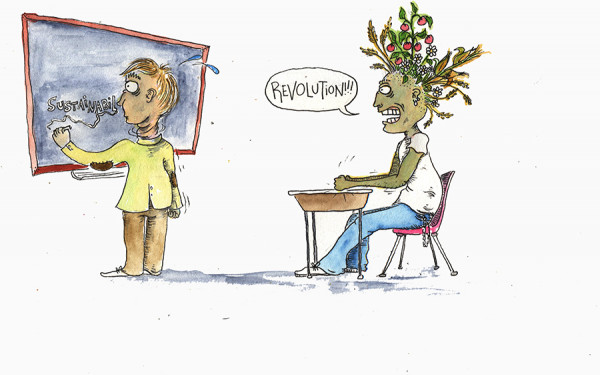

Sustainable development has become more and more fashionable since the 1990’s, when the Brundtland Commission coined the concept. Energy is an important part of sustainable development—and many groups around Montreal recognize the urgency in changing our energy sources from fossil fuels to renewable ones.

Just last week Divest McGill organized a sit-in after that university’s administration announced it would not withdraw its investments from the fossil fuel industry. In wake of the protest, Principal Suzanne Fortier met with the group, but refused to concede the legitimacy of their demands.

At Concordia, circumstances are slightly different. Concordia was the first Canadian university to begin the divestment process in 2014, when it announced it was pulling out $5 million from the fossil fuel industry. However, it has only partially divested, and it is unclear how much university money continues to fund fossil fuels.

Concordia is home to a wealth of organizations that contribute to sustainability. Sustainable Concordia monitors and promotes sustainability around campus. The Sustainability Action Fund makes funds available for student initiatives related to the environment.

We even have the Loyola Sustainability Research Centre whose director professor Peter Stoett will be a visiting scholar on climate justice at the University of Reading this summer. Not to mention numerous other groups like Le Frigo Vert, the Concordia Greenhouse, the Concordia City Farm, the Hive Cafe, the Concordia Food Coalition, and others that work to make the local economy sustainable. Through the actions of its students, Concordia has become a leader in sustainability.

The same can’t be said of decision-makers in the provincial or national governments—especially on the subject of energy, where the dialogue is particularly rancorous.

Just this January, in response to Montreal Mayor Denis Coderre’s official opposition to the Energy East pipeline, Rona Ambrose, the interim leader for the Conservative Party, told Prime Minister Trudeau to “stop using his cell phone for selfies […] and pick it up and call Denis Coderre and fight for natural resources”.

Similarly, Brad Wall, Premier of Saskatchewan, tweeted that Coderre and the rest of Quebec should “politely return their share of $10B equalization supported by west #EnergyEast.” Keep in mind these aren’t irrelevant trollers on the CBC’s comment section—these are leaders of western provinces.

Prime Minister Trudeau has shown interest in continuing to exploit Canada’s fossil fuel industry, saying he wants to get our natural resources to market in a responsible and safe way, and that pipelines will pay for the green economy.

The Canadian government has also committed to climate change action at COP21 last November, and has been considering carbon pricing as the centerpiece of their climate policy. What seems to be a moderate, agreeable position is questionable, if not outright objectionable, upon closer scrutiny.

Robert Pollin, professor of political economy at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, outlines the steps for a transition from a fossil fuel-dependent global economy in his 2015 book Greening the Global Economy.

His argument is based on the figures provided by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the UN’s research arm for climate science and policy. For meaningful climate action, Pollin calculates that fossil fuel consumption would need to decrease by roughly a third in the next twenty years.

Alternative energy is a critical variable in the equation, and simply switching to low-carbon fossil fuels, namely natural gas, won’t cut it. Even if we managed to switch the world’s coal consumption—the dirtiest of fossil fuels—to natural gas, we wouldn’t even be halfway towards the Pollin’s target.

The problem isn’t in the science or policy options. It’s clear what needs to be done if your main objective is climate change action. Except, there’s a difference between science and public policy, and politics mediates the two. The energy question boils down to the objectives we set for ourselves, as a country and global society.

So when I heard professor Amano’s question about Canada’s energy while in that conference in Japan, I nervously raised my hand. I described the risks that we’re taking by continuing down the road we’re on. I described how Canada has a horrible track record in respecting the rights of indigenous people, and how pipeline projects amplify to this shameful colonial tradition.

I said that building North America’s largest pipeline—Energy East—at a time when we should be cutting back fossil fuels and expanding clean energy technologies contradicts our efforts for climate change action. Energy East promises to fragment Canada’s natural landscape and cause significant ecological harm.

Not everything is doom and gloom, though. We need to recall the politics of it all. We shouldn’t assume that proponents of fossil fuel development are malicious or greedy— just as environmentalists shouldn’t be stereotyped as ungrateful welfare recipients. This kind of language corrodes our politics.

If we think of our future in terms of “us versus them,” we’re missing the point altogether. Those whose livelihoods depend on the fossil fuel industry ought to be worried about the economy and their jobs, because those things are essential parts of their lives.

But Canadians should know that something is lost when we refer to them as taxpayers, as if the bonds of citizenship could be reduced to the money we contribute to government coffers. The common good requires more than jobs. Where those jobs come from is also important.

The way that Canada responds to the question of energy will prove to be a defining moment for its history. It’s about more than just resources, federalism, or questions of east Canada versus west Canada. Above all, it offers a chance to reinvigorate the ties of citizenship across the country.

Most importantly though, is we cannot entrench ourselves into uncompromising positions because it prevents us from seeing things from another point of view. As the old proverb goes, “If we continue where we’re headed, we’re liable to end up where we’re going.”

(WEB)_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)