A Room With Some Views

“I Hate Going to Readings”

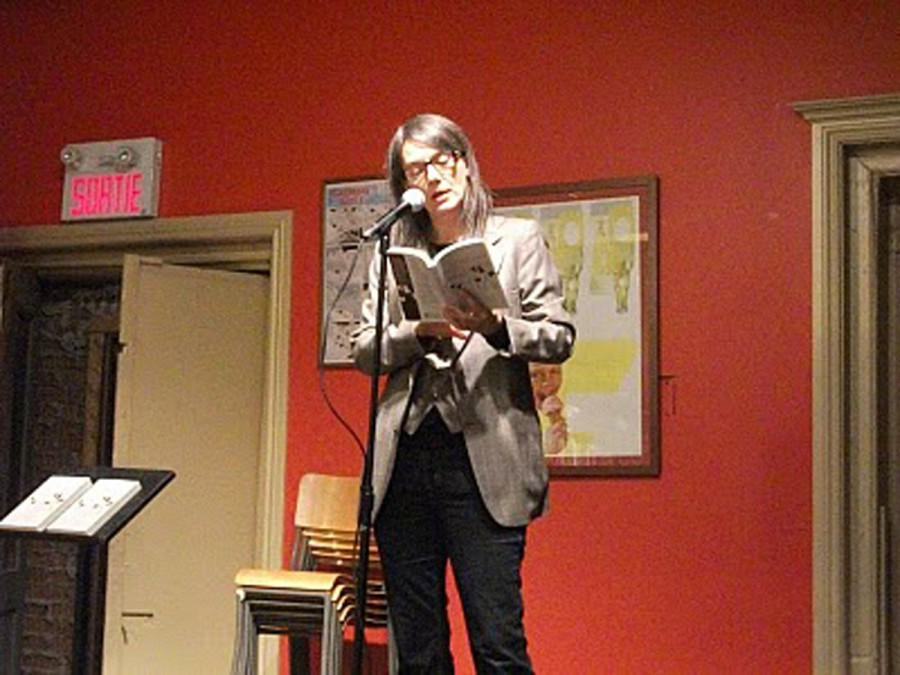

“I hate going to readings,” said my friend’s roommate. This right before my friend and I walked to hear Sina Queyras read from her first novel, Autobiography of Childhood, at Drawn & Quarterly. He said he didn’t need to know how the writer intended the characters to sound. Fair enough. But most of the time, the audience and the questions that arise after a reading can be worth it.

I was curious too, because, from what I had read, her novel was an attempt to narrate trauma: a family that has never quite recovered from a death must face yet another. And after any traumatic event, one cannot help but reflect on the past—sometimes, in the hopes of discovering where it went wrong.

This kind of reflection can be cathartic—freeing, even—or, it can lead to solipsism. And then there’s the fine line between solipsism and loneliness (or is there?), so why not have someone’s mental states read out loud? Also, Queyras usually writes and reads poetry, so I was curious as to what her fiction would be like.

Autobiography of Childhood is divided into six sections: one for each of a family’s six members over the course of the same day. Each section is an opportunity to experience the mind of its subject. Queyras chose to read Bjarne’s section. Bjarne’s mind is slowly collapsing onto itself—or at least every single one of his memories is. The rhythms and imagery haunted the passage, which reflected his mental decline: the sounds of trees bother him, even though he lives in a windowless apartment; he “hears trees without looking.” He has too many feelings.

Most of the time, I shifted between listening attentively and drifting off—lulled by his torturous thoughts, his fixations on sounds that weren’t there, or even his slow and steady retreat from the physical world. Perhaps I was just distancing myself from the fear that “this could happen to me,” or perhaps my desire to humanize him was also an attempt to understand him. Whether I was swallowed up in the language or by Queyras herself, I’m not sure. Just a few days later, I can’t remember the reading itself, but rather the feelings I left it with.

Even so, I remember the attentive silence—from what I could tell, people were paying attention (even those who were left standing; Drawn & Quarterly was obviously too small a venue). And I’m even more certain that my observation of the audience is correct because the Q&A afterward led to a great conversation on writing, which every reading should have, but somehow never seems to.

It also seemed as though everybody was thinking the same thing. For instance, right next to me sat a recent graduate with an MA in English. Throughout the reading, he feverishly jotted down some notes. The first thing he wrote quickly was “stream of consciousness.” I had written down the same before, but then we both thought about Virginia Woolf, and then came the question “Were you inspired by Virginia Woolf’s Waves?”

“Yes,” replied Queyras.

Then came a question from one of her students—something to the effect of whether certain parts were cut out or rewritten.

“Ninety per cent of the book was cut. I was trying to make Bjarne pretty and that’s why he was annoying. I was also holding out when I was writing him. But he’s just a guy who had a bad turn tonight. I realized that when lives become anecdotes, they’re less interesting.

This book is actually the fifth version of the book. The voices of all the children were not distinct enough—the italicized part at the beginning of the book, that remaining 10 per cent—was the entire voice for the novel. Each character now has a distinct voice. There are distinct differences in coping and this had to be reflected in the book.”

But the parts that have been cut out are still around. “There’s a loving file on my desk. Writing doesn’t go away,” she said.

Queyras wrote Autobiography of Childhood at the same time as Lemon Hound, a poetry collection she published in 2006.

“This is the first book I’ve written that I could explain what distinguished poetry and prose.”

After the reading there was much discussion, too. Many of the attendees had never read Woolf’s Waves before, and some students, already crammed with so many course readings, were trying to decide whether they should in fact read it.

“You like reading about all things grim, so why not read Woolf? Waves is just so beautifully written.”

People don’t always go to readings to listen, but sometimes to do other things. People still show up late to readings. People still avoid readings. People still hate readings. But at least they ask questions.