Tuition Hike Questions Remain

PQ Solution Still Unclear to Students

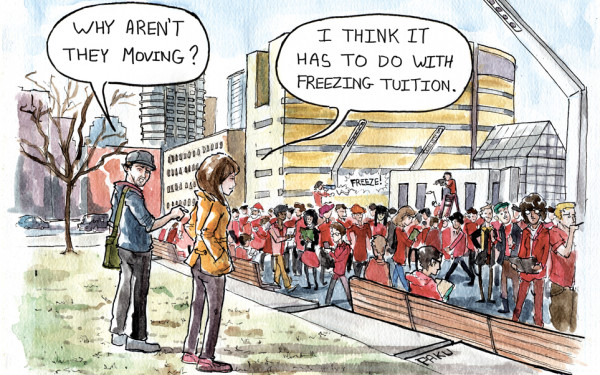

There’s been a lot of talk about victory since Premier-Elect Pauline Marois announced her plan to freeze tuition in Quebec. And while student leaders call this a win, they’re not calling it the end.

“I don’t think [the tuition debate] is over, but it’s dramatically going to change,” said former Concordia Student Union president Lex Gill. During her term, Concordia voted to go on a weeklong strike, and several member association strikes continued in the weeks and months afterward.

“Let’s face it, this is a victory,” Gill said. “It’s just not the way we thought it would happen; it’s not the way we thought we would win.”

Marois’ announcement was brief and without much substance. Both the hikes and Law 12 will be repealed, said the new premier, but little is known about how or when that will happen.

Marois will most likely strike down both with a ministerial decree sometime between taking power on Sept. 17 and appointing a cabinet two days later. What’s unclear, however, is how her new education minister will handle the budget shortfalls.

Universities, Concordia among them, will continue to bill students at the increased rate—$254 more than last year’s tuition. Until they receive an official directive from the Ministère de l’éducation, du loisir et du sport, they don’t really have a choice. As far as their budgets are concerned, the amount owed to MELS hasn’t changed.

If Marois follows through with her plan, Concordia will face the logistical nightmare of then returning money to its student population. It’s not likely there is a solution that will not be costly, timely or both.

There are also 26 students at Concordia facing charges for actions during the strike, and a lot of fresh scars from seven months of action that won’t heal easily.

Gill feels that while the community can learn from the movement, there’s no easy fix to what she refers to as a “simultaneously violent and bureaucratic crackdown on student

organizers.”

“It’s the result of a system that is unable to handle a true democratic process,” she said. “I don’t know if that’s something you can legislate out because it’s part of the legislative process.”

One way the new government plans to address some of these lingering issues is during a proposed academic summit, a process that Marois promises to start in her first 100 days in office.

“[The Fédération étudiante universitaire du Québec] will be at this summit. We’ve been asking for a summit on universities for a long time,” FEUQ President Martine Desjardins said. “It’s a golden occasion to evaluate the system. We will not miss an opportunity like that.”

Moving forward, Desjardins is optimistic but cautious. “We can say ‘mission accomplished,’” she said, adding that FEUQ feels “there aren’t any more reasons to continue the strike.”

Like Gill, however, she recognizes there are no easy fixes, and this summit will require lengthy dialogue between all parties.

“We’re going to work with the rest of the academic community to ensure their support. That’s how we will manage to bring important points to this summit,” she said. “We cannot rely on governments or parties to do it, but on our allies within the academic community.”

The problem with that, of course, is that within the academic community there is little to no consensus on what should be asked for.

“The student movement has always been splintered, not in two but in a thousand little pieces,” Gill said. “And that’s normal and healthy for a big movement.”

Ultimately, however, Gill is “not really worried.”

“There are so many fantastic student organizers,” she said. “I’m happy being part of the old guard, but I don’t think the responsibility is totally on our shoulders now. There’s a new generation of students who need to pick up the fight.”

—with files from Pierre Chauvin and Justin Giovannetti

_900_598_90.jpg)

2_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

05_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)