This Is Everyone’s Problem

Choreographer Daina Ashbee’s New Dance Performance Tackles the Subjects of Abuse and Interconnection

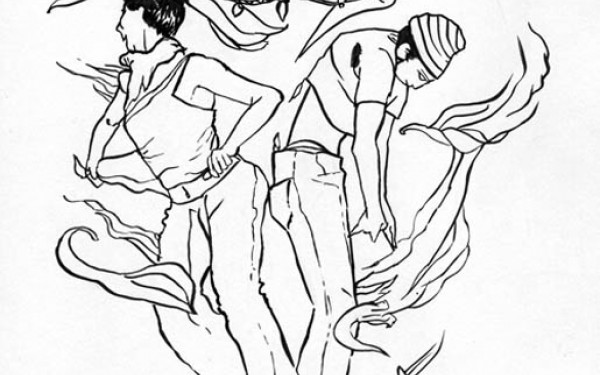

A dancer flings her body to a wall while another violently shakes a clothing rack that almost topples over her. These are some of the disturbing yet highly symbolic images the audience can expect to see at Unrelated, a major dance production choreographed by Daina Ashbee.

While the main focus of the show is to portray the suffering related to the crimes and violence against Aboriginal women in Canada, the piece also highlights the different types of abuse an individual can fall victim to. The title of the performance, Unrelated, strategically encompasses this notion.

“There isn’t just one type of violence; there exists the violence that we inflict upon animals in our food production, there is child abuse, there is animal abuse, there is the violence on the environment,” Ashbee explained.

At the root of these various types of abuse seen in all facets of present-day society are the individual and the loss of feeling like a collective entity as human beings, according to Ashbee.

“If we all interacted as though we were all related, connected, and if we felt empathy for each other, we wouldn’t have these greater issues,” she said.

The disturbing images in the routine are meant to show the result of this detachment from one another.

“The piece is going to be dark and it’s going to portray the disconnections between the dancers, their bodies and all the horrible things that we do since we no longer strive to relate ourselves to others,” Ashbee said.

Another striking feature of the performance is the apparent nudity of dancers intended to depict the vulnerability of victims who experience abuse.

“Having the female dancers naked and doing all of these violent gestures is effective to show the audience that this is what vulnerability looks like. I want the audience to empathize with the dancers and the victims they are representing,” she said.

The choreographer’s personal struggles growing up and her activism with regards to missing and murdered Aboriginal women are also major sources of inspiration for the piece.

“I am drawing from quite a few of my experiences as a young woman growing up in my family and witnessing the cycles of abuse and addiction, which became a part of me. I had a very different way of dealing with the addict in me. I had an eating disorder,” Ashbee said solemnly.

As her grandmother dealt with alcoholism, Ashbee struggled with anorexia. The dramatic way in which the dancers move is meant to portray the cycle of abuse on oneself and the interconnectedness of various types of violence.

“The movement is drawn from my body; a lot of it comes from the self-destructive behavior of an eating disorder as well as the shame that was carried on from my ancestors,” Ashbee said.

“Even though I wasn’t dealing with alcohol or drugs, it still felt like it was all related,” she added.

Having a rich ethnic background has fuelled her to participate in raising awareness about the crisis of missing and murdered Aboriginal women.

The recent disappearance and death of 15-year-old Tina Fontaine, who was of Sagkeeng First Nation descent, has sparked renewed calls on the federal government to take action on the issue and launch a national inquiry.

“It hurts me when I read all these news articles, but I think as an artist if I can get people to relate more to these women and their families, my [form of] expression being dance, then that’s what I want to do. I want to join in their grievance and activism to better understand their pain, emptiness and struggles,” Ashbee said.

Part of her research also included tackling her own consciousness to further understand the subconscious realm that moves human beings to act the way they do towards others.

“I wanted to explore how the energy that I emit from my body affects people. Understanding that I’m not just matter and I don’t really have an ending was the basis for my research,” Ashbee explained.

Seeing the individual as a never-ending entity that extends from the subconscious all the way to the energy that is emitted into the universe is a way of seeing that everyone is inadvertently connected.

“We want to turn a blind eye on [abuse] and act as though it’s not our problem but it is since we’re all related, this is everyone’s problem,” Ashbee said.

Unrelated // Oct. 3 and Oct. 4 // Montréal, arts interculturels (3680 Jeanne-Mance St.) // 8 p.m. // $18

Correction: This article originally stated there would be screams during the performance. In fact, the noises will be produced by the movement of the dancers. This article has been updated accordingly. The Link regrets the error.

2_900_598_90.jpg)

1_900_598_90.jpg)