Organs and Operating Systems

The Medical Community Gets a Robotic Helping Hand

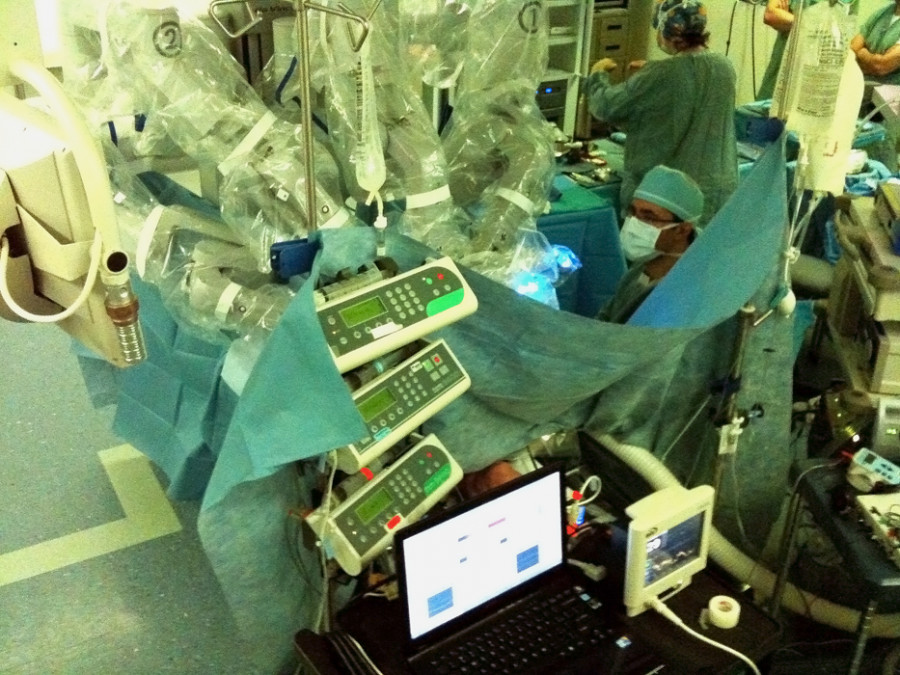

Several weeks ago in the Montreal General Hospital, 68-year-old Gilles Lefort was put to sleep and had his prostate cancer successfully removed—by robots.

No longer solely the domain of Brave New World style science-fiction, medical robots are quickly becoming widely used in surgery rooms. McSleepy, an automated anesthetic machine and Da Vinci, a set of mechanized arms, are subjects of ongoing controversy within the medical community. Cost, efficiency, malpractice and ethical considerations have some questioning the benefits of robot-assisted surgery.

Of Machines and Men

Humans are not left out of the operating room altogether—at least not yet.

“The anesthesia process is a complex one, in which many variables must be accounted for by professional experience and intuition,” said Dr. Pavel Straka, an anesthesiologist. “If doctors become replaced and the procedure goes wrong, McSleepy is incapable of fixing it.”

Dr. Thomas Hemmerling, the anesthesiologist during Lefort’s surgery, maintains that within 10 years, robots will be ever-present in most operating rooms. That is not to say that doctors will not be needed.

“Robots allow doctors to work to their fullest potential and to provide the patient with the greatest benefits possible,” said Hemmerling. “The two work in conjunction.”

In fact, Da Vinci’s arms are basically an extension of the doctor’s own body. The surgeon gazes through a computer console to direct the procedure. An enlarged, three-dimensional view of the space helps the doctor clearly see where the arm is operating.

The same procedure applies for the anesthetic, as Hemmerling oversees the operation and will manually intervene only in emergency situations.

“McSleepy is an automated box that dispenses anesthetic and self-monitors the drug levels within the patient,” said Hemmerling.

It allows the doctor to examine other vital signs, such as air tube obstruction, that are sometimes overlooked when too much attention is paid to monitoring drug levels.

A big issue is who is responsible in the instances where something does go wrong. Current malpractice laws hold the doctor accountable for any death or injuries sustained by the patient, even in cases of negligence. The litigation process is complicated because there are no clear-cut laws regarding robots yet.

Hemmerling believes that future laws on robotic malfunctioning will most likely be similar to today. If a surgeon messes up, he’ll be the one responsible. However, if it is not the doctor’s fault, the company that produces the malfunctioning robot will be held liable.

The Deepest Cut

Until recently, large incisions were required to gain access into the body and traditional surgery was considered a relatively invasive procedure, in that it ruptures the skin or requires entrance into a body cavity. The doctor gained access by splicing and opening the skin like a flap, in order to prod the tissues and organs involved.

Robotic-assisted surgery is considered the most minimally invasive method of operating. The instrument enters the body through a precise, keyhole-sized incision rather than a gaping wound. Following his surgery, Lefort reported to The Gazette that his recovery was quick and painless.

Precision is enhanced, as well. Da Vinci’s mechanical hands are far more dexterous because they can move in directions that are physically impossible for human arms. They can perform in much smaller areas of the body with fewer tremors than a human hand, increasing stability and accuracy.

Money and medicine

Some still believe that the benefits are simply not worth the hefty price tag. The Canadian Urological Association Journal reported the cost of a robotic prostate surgery to be $3,800, whereas a conventional operation costs $450.

“I do it effortlessly and cheaply everyday. It would be a lot easier [to demonstrate the ease of operating] if you could see any of us in action,” said Dr. Straka.

Dr. Shantanu Nundy is a resident physician who focuses on preventative healthcare. He believes that medical funds should be directed towards preventing illnesses, rather than on elaborate machines. For him, health education is an integral aspect that is often neglected in a medical system saturated with patented drugs and new technologies.

“Obviously prevention is better than treatment, better for patients and for the health system at large,” Dr. Nundy said. “With respect to prostate cancer, however, unfortunately we do not have good ways to detect it at an early stage. Perhaps costs should be directed towards finding ways to prevent the disease before it forms and degenerates.”

Despite the reservations of some members of the medical community, it is a likely possibility that taxpayer dollars may continue to be directed towards surgical robotics.

In 2009, a startling 75 per cent of prostate cancer surgeries were performed with the help of Da Vinci. For Catherine Mohr, director of surgical research at Intuitive Surgical, investing tax money in robotics is a no-brainer. She maintained that the funding is an economically efficient way of reducing total hospital costs.

For example, keeping a patient following their surgery costs the hospital approximately $1,500 per day. With minimally invasive procedures, the patient is released two-and-a-half days earlier on average. The money that is saved compensates for the initial expense of the robotics and maintenance costs, and even leaves the hospital with a $500 surplus.

The simple math helps to explain why many hospitals are quick to pump funds into developing robotics. But comments on Mohr’s health-care blog in The New York Times reveals that some are not as keen to embrace a technology they consider to be nothing but hype.

“[Robotics] spread because of doctors’ desires, skillful marketing and the herd mentality of hospital executives. The same story was true for CT, MRI PET, drug-eluting stents and loads more technologies that are already overused, have marginal if any beneficial outcomes and have helped rocket up health care costs,” one commenter wrote.

However, one patient detailed his personal experience with robotic surgery and maintained the experience was a positive one. Last March, he had a quadruple heart bypass operation using minimally invasive surgery. He regained full recovery within two weeks and returned to work in three weeks. His brother received a similar operation five years ago using traditional surgery and was barely able to walk a block even six weeks later. His anecdotal recount seemed to convince some on the site, while pushing others still further in their fight against robotics.

Dr. Robot, MD

For those unwilling to jump on the robotics bandwagon, Da Vinci and McSleepy present an eerie prospect for the operating room of tomorrow; an operating room resembling an assembly line of car parts, with human surgeons and anesthesiologists disposed of altogether. This scenario is not far from Aldous Huxley’s macabre portrayal of a mass-produced, mechanized society.

Yet others maintain that we have only just begun to reap the benefits offered by robotic surgery. To view the transition into robotics with such a critical eye is to do a disservice to a potentially life-changing technological advancement. What is clear, however, is that further empirical research is required to substantiate any claims about the overall benefits of robotics.

In the brave new world of surgery, it remains to be seen just how the symbiotic relationship between man and machine will evolve.

This article originally appeared in Volume 31, Issue 14, published November 16, 2010.