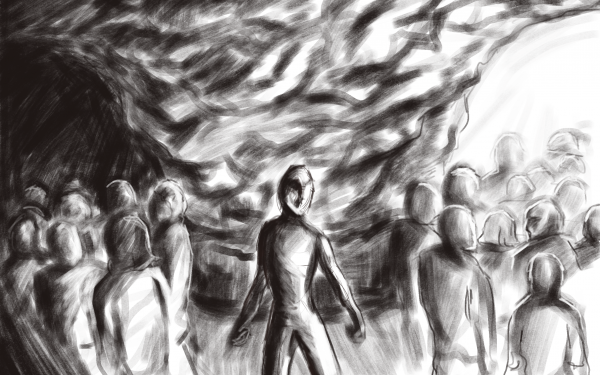

The critical condition of crowded Canadian emergency rooms

Long wait-times, understaffing and death wait behind the doors of an overcrowded ER

On a July night in 2021, Zoe Katz, then 20, went to the Montreal General Hospital after fainting and hitting the back of her head. She waited eight hours to be treated with stitches.

“I touched the back of my head and my fingers were wet [with blood],” Katz said.

After a few hours of waiting in the emergency room, Katz asked to be given a temporary solution. She was given a “flimsy bandage” by a nurse with “no other words about what would happen.”

“I felt like she didn't really care whether I lived or died,” said Katz. “I cried a couple of times because I had read news about people being very neglected by the medical system and just undergoing really scary medical mishaps in ERs (Emergency Rooms).”

“It's really jarring seeing blood come out of the back of your head and not really having a measure of where or how deep the wound is.”

According to Katz, she was in the third priority (urgent condition) range out of the five levels at the ER. Katz entered the ER at midnight and left around 8 a.m. that morning.

“The one takeaway I got [from my experience] is that I want to live my life in a way that minimizes my exposure to the ER,” said Katz. “I don't want to be there and I don't want to be in hospitals, so I just live my life as healthily and away from harm as possible.”

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the strain on Canada's healthcare system has increased, with emergency departments growing more overcrowded and workers more overworked. According to the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians, an estimated 8,000-15,000 Canadian patients die unnecessarily each year as a direct result of hospital crowding.

Dr. James Worrall, an emergency department physician at the Ottawa Hospital, said ER crowding and wait times are “just as bad or worse” following the pandemic.

“The situation almost every [public] hospital in North America faces is that there is not a bed available,” said Worrall. “So, the patient waits in the emergency department for a bed. That wait may be hours, it may be days. This reduces the ability of the emergency department itself to accept and care for new patients.”

A crowded emergency department does not mean huge crowds in the waiting room. It means all of the hospital’s care spaces and stretchers are occupied by patients who have been admitted and are waiting to move upstairs to a hospital bed. “Sometimes all our stretchers are full, and we’re packing people away in corridors,” Worrall said.

Before moving to Ottawa, Worrall worked at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal from 2005 to 2007. “We would have patients waiting for a week in the emergency department,” he said. “I mean, things are bad where I work now, but not that bad.”

In Quebec, there is a centralization of control and decision making around healthcare at the provincial ministry level. Municipalities lack the ability to hire as many doctors as needed, or to create innovative solutions that work for their hospital or their region, according to Worrall. Because decision-making power is decentralized in Ontario’s healthcare system, there is more municipal autonomy with governance, decision-making and regulatory matters.

The Plans régionaux d’effectifs médicaux (PREMs) were established two decades ago with the aim of promoting a fair distribution of family doctors throughout Quebec. The PREMs are assigned by region. All doctors employed in the public system must have a PREM and dedicate at least 55 per cent of their practice to the region where it was granted—otherwise they are docked 30 per cent of their pay and prevented from reapplying for three years.

The permits are distributed assuming that a doctor will manage a full patient load alongside their additional duties. However, if a physician takes parental leave, gets sick, or scales back their hours for any reason, there is no measure for other doctors to pick up the slack.

PREMs are also non-transferrable. If a physician like Worrall leaves the province, moves to the private system, or retires, the permit is lost forever. This means that hospitals can be left understaffed, and further, overcrowded.

“[PREMs are] just so centralized and bureaucratic, it is far less efficient,” said Worrall. “Another difference in Quebec is within hospitals, there is far greater acceptance of the idea that patients don't need to come to the emergency department; they're using the system irresponsibly. And when people get admitted, they can just stay in the emergency department hallway for days and days.”

Patients are often blamed for visiting the ER inappropriately, when in reality, Canadian health care systems are designed to funnel patients towards the ER, said Worrall.

Dr. Bianchi, a 45-year-old emergency department physician at the Hôpital de Verdun—granted a pseudonym for privacy reasons—said the majority of people waiting in ERs are there inappropriately.

“As a doctor, you're tired and you just intubated a baby. You had a person that died in front of you because he had a car accident,” said Bianchi. “And then you see this person who has a runny nose and he doesn't want to go to work tomorrow. This is the reality.”

In 2021, Bianchi was working in Verdun when a patient suddenly suffered a cardiac arrest. “There was no space [in the department] and there were no monitor pads [available], so it was complete chaos. Of course, we took the monitor pads off one of the patients, because this one was literally dead,” he said. “At some point it's too much.”

In Montreal hospitals, emergency department occupancy rates hover well over 100 per cent in most cases, sometimes topping 200 per cent. According to the Index Santé website, only four of the 21 hospitals in Montreal were reporting occupancy rates under 100 per cent on Nov. 27. The highest traffic was reported at the Royal Victoria Hospital, with an average waiting room time of over 10 hours and an average time spent waiting on a stretcher surpassing 32 hours.

“We need a model of care where the inpatient parts of the hospital have to be able to accept whatever comes their way,” said Worrall. “They need to be able to flex up and bring in more people when needs are higher and then flex down when demands are lower.”

In 2004, the Department of Health in England set the target of a maximum four-hour wait in Accident and Emergency (A&E) from arrival to admission, transfer or discharge. The aim was to reduce waiting times and control crowding. This target was initially set at 98 per cent compliance, and adjusted to 95 per cent in 2010.

Studies have shown that this standard has yielded positive outcomes for patient care. The standard has been linked to better hospital bed management and reducing patient waiting times and mortality rates. Within a year of visiting A&E, patient mortality reduced by 0.3 percentage points, representing 15,000 fewer deaths in 2012-2013.

Data from England’s National Health Service also shows that in 2002, 79 per cent of patients spent less than four hours in A&E, while in 2005 (after the target was introduced), that level was 98 per cent.

“It starts with the government saying, ‘We're not accepting the current status quo,’” said Worrall. “The emergency department is effectively the waiting room for the rest of the hospital, and that's not okay.”