Minimal and Surreal

A Look at Alan Reed’s Stark Isobel and Emile

Isobel and Emile is a story that begins at the end of a love affair.

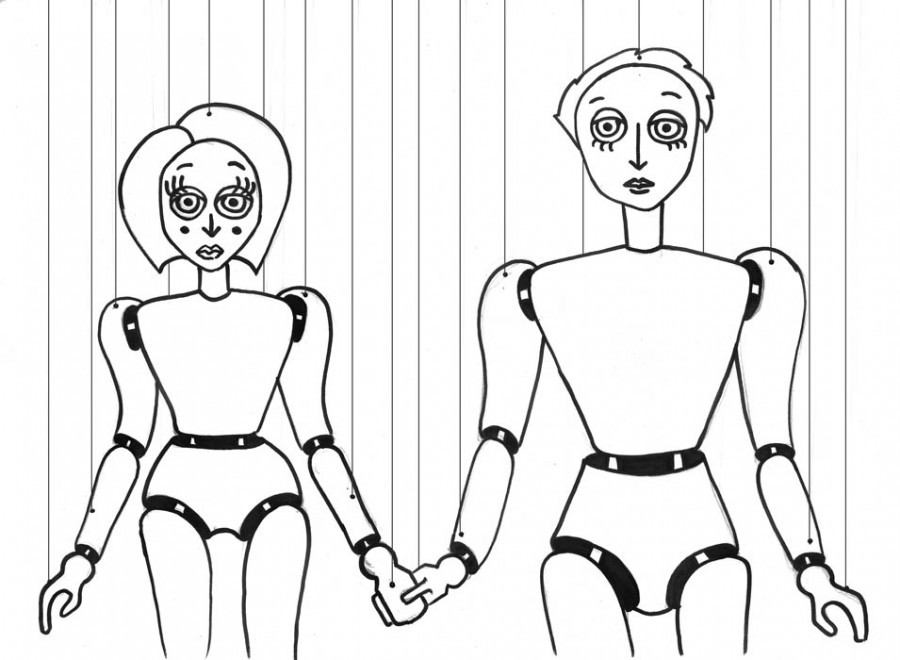

Emile leaves for the city. Isobel stays behind. Emile is a puppeteer. In the city, he’ll brood on the love that he left and try to make some sense of it in his work. Isobel will deal with the silence left by the absence of Emile.

She’ll live in the room that he left, a room above the town’s grocery store. She’ll beg for a job in the store, and work until her body hurts.

This is the first novel from Alan Reed, previously the author of For Love of the City, a collection of poems, who currently resides in Montreal. Reed’s prose is comprised almost entirely of simple and declarative sentences. So the novel begins: “They are sitting. There are two of them. They are sitting beside each other. They are in a room. There is a bed in the room. There is a sink. There is a window. There is a door…” It goes on and on (and on) like that.

There is really no getting around this prose style. The flat delivery, repetition and staccato rhythm are relentless. You’ll be able decide early on if it works for you or not.

If it does, it’s probably in part because Reed knows what he’s doing. A student of semiotics with an interest in the failure of language, as he puts it, and in silence as an ideal, Reed has said that he writes to point out a quiet place existing beyond what can be written.

The prose style could be seen as indicating what cannot be expressed when a love comes to a conclusion; or as reflecting how deeply each of the protagonists is set into themselves and their circumstance. As every sentence is so curt and minimal, so are the characters’ selves starkly defined in the absence of each other.

On the other hand, if it doesn’t work, it’s probably because these explanations aren’t pressing enough to justify the style. To be convinced by Isobel and Emile requires close attention on the reader’s part.

For many, the book will seem not worth such attention, because until the moment you are convinced of Reed’s deeper intentions, the prose can seem gimmicky or pretentious. It’s fitting that a book about a couple divided would be so divisive.

This article originally appeared in Volume 31, Issue 12, published November 2, 2010.

__600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)