God gone corporate

How the rapid growth of Pentecostal megachurches exploits corporate tactics to fill a void of global disconnect

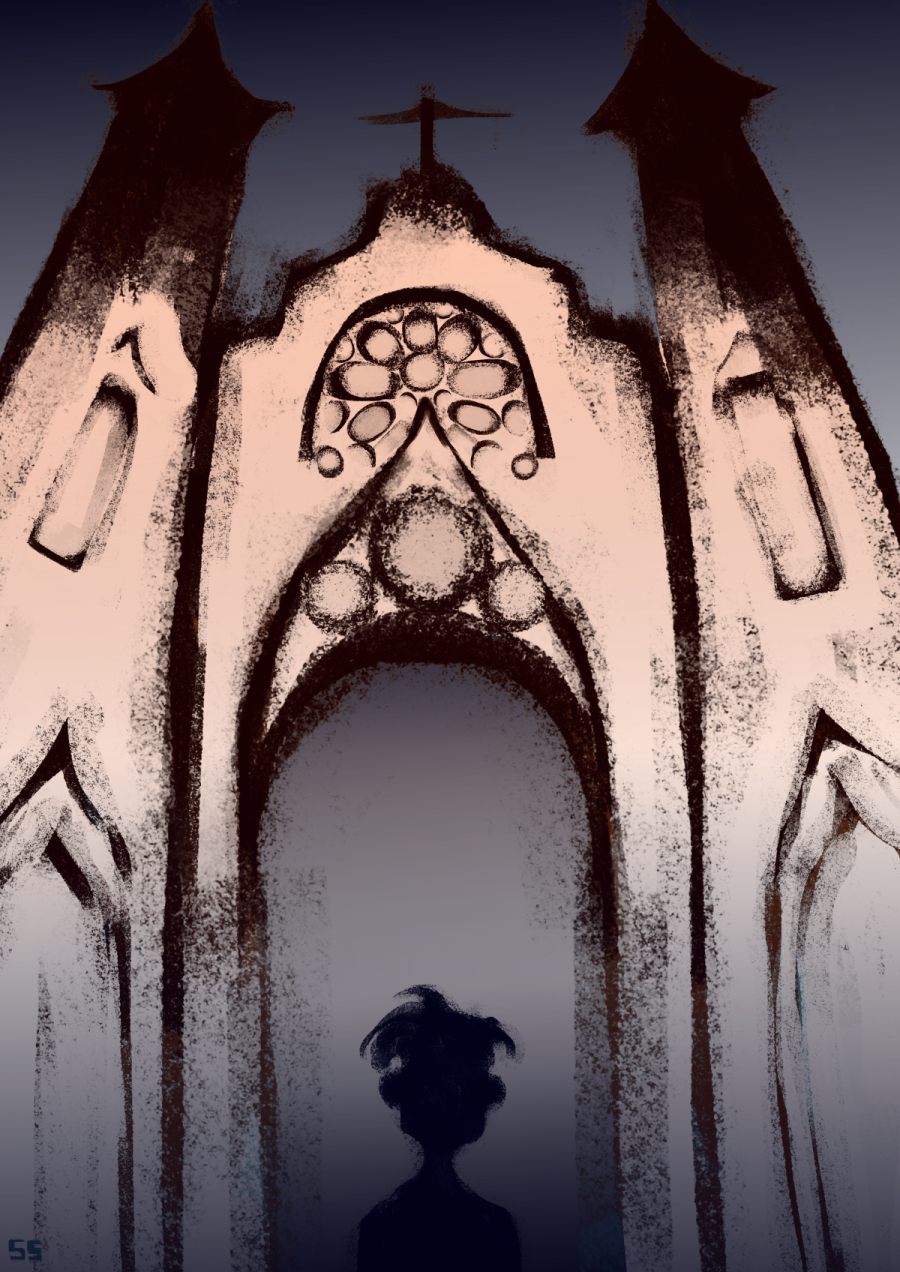

On any given Sunday in Longueuil, pastor Selvin Cortez greets a congregation of 4,000 with an infectious smile as the concert band behind him strikes its first chord.

Cortez claps his hands over his head in sync with the band, gesturing to the congregation to join him in song and worship. At the same time, an audience of tens of thousands watches online.

Église Nouvelle Vie in Longueuil is one of 35 megachurches in Canada. The technical definition of a megachurch is the size of its membership, a “sustained weekly attendance of 2,000 persons or more,” according to the Hartford Institute for Religion Research. Other characteristics of megachurches include multiple locations, online influence, a charismatic pastor, and services that rely on repetition and invoking the mystique.

Just as fast-food chains grew to replace the local diner, megachurches emerged to fill a market demand for convenience and accessibility that smaller churches couldn’t compete with. Yet the frequent criticisms of megachurches’ corporate expansion are dampened by testimonies of the strong sense of community they cultivate.

Nouvelle Vie has eight sites across the province, yet its online presence in other Francophone countries is arguably more influential. A quick search of its YouTube channel brings up 256,000 followers and 1,700 videos organized into hundreds of playlists ranging from “Morning Coffee with Pastor Claude,” “The Path towards Resurrection,” “Christian Songs for Children” and “Advice for Romantic Relationships.”

Emmanuel Hyppolite has attended Nouvelle Vie on and off for 20 years. After several years of trying different churches, Hyppolite always returned to Nouvelle Vie.

Hyppolite described the community at Nouvelle Vie as a “place where I was always welcomed, loved and accepted despite my mistakes, including my problems with addiction.”

“Its message is that no matter your past, no matter what you have done, we will welcome everyone,” Hyppolite said.

He claims that the connection to Jesus cultivated at Nouvelle Vie has helped him become a “better citizen, a better father and a better son.”

Most megachurches, including Nouvelle Vie, have their roots in smaller Pentecostal churches. Pentecostalism, the fastest-growing religious denomination in the world, is based on spirit-driven worship, with an emphasis on music, chants and a personal connection to Jesus.

While megachurches are commonly associated with the US, their true epicentre is the Global South—countries in Africa, South America, the Caribbean and Asia.

As the West has become more secular, historically colonized and missionized countries have experienced a momentous growth in church membership, according to Andrew Gagne, head of the theology department at Concordia University. In fact, Gagne explained that religious leaders and missionaries are now expanding their reach back to the West to “re-Evangelize those who missionized them.”

The US’s biggest megachurch, the Lakewood Church in Texas, maintains 45,000 attendees per week across its multiple locations. Yet this pales in comparison to the 120,000 who attend the Deeper Life Bible Church in Lagos, Nigeria, or the 200,000 who attend Yoido Full Gospel Church in Seoul, South Korea.

Critics, including evangelism and methodist studies scholar Laceye Warner, claim that megachurches have lost touch with any true biblical message, becoming hyper-focused on profit and expansion.

In Gagne’s words, megachurches are designed to deliver the “Walmart church experience.” They offer churchgoers neatly packaged Sunday entertainment that even covers childcare. Worshippers may simply sit back in the pews and watch the sermon flash on the teleprompter while taking in the opulent display of chanting and concert-quality music.

“These kinds of churches are essentially a franchise, and their leaders are like religious entrepreneurs,” Gagne said.

If megachurches have become a franchise, then Gen Z is one of their key target audiences. With its emphasis on music, experiential worship and acceptance of differences, the Pentecostal model found in megachurches has a clear appeal.

Kaylee Booth is a devoted member and youth leader at the Hope City Church in Edmonton, a Pentecostal church with 2,000 to 3,000 weekly attendants across locations. Booth says the church has witnessed a huge increase in Gen Z membership. Hope City’s youth group, The Project, grew from approximately 200 members to over 900 in just the past year. It is now the biggest Christian youth group in Canada.

Up until a year ago, Booth identified as an atheist. A string of fate—tied up with her love of worship music and a charismatic pastor’s son she met on Snapchat—led Booth to join The Project. Two months later, Booth was baptized. Now, a year later, she has applied to a bible college to pursue her own calling as a pastor.

Because of their large social media presence and accessibility, megachurches and their online preachers are often Gen Z’s entryway into Christianity. Booth believes that churches moving online is a necessary adaptation to modern needs.

“I don’t think it takes the sacredness out,” Booth said. “I mean, the Church is just a building. Going online helps us reach more people.”

For many Gen Z Christians like Booth, joining a church was a remedy to their sense of isolation and struggles with mental health.

“I just feel like our generation is quite lost,” Booth said. “We’re looking for answers and we can’t find them and [we’re] lacking a sense of belonging.”

_600_832_s.png)