The Pill problem

Birth control users speak out about their experiences on different forms of hormonal birth control

Gabrielle Paquet was first prescribed birth control pills at 14 years old. She received the medication due to severe and painful menstrual cramps, or dysmenorrhea.

“I was missing so much school, and seriously, I was on the floor crying in pain,” she said. “That’s how bad it was.”

Paquet did an ultrasound to see if she had endometriosis, a condition where tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows on other parts of the body. Endometriosis affects at least one in 10 women, according to Endometriosis Network Canada.

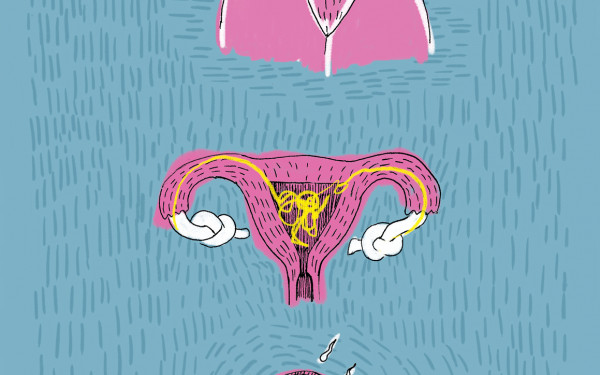

When she found out she didn’t have this condition, her family doctor instead prescribed her birth control pills—a type of oral contraception that uses hormones to prevent ovulation. The pills can either come in the form of a combination of estrogen and progestin or a progestin-only pill.

Many people with uteruses experience heavy menstrual bleeding at some point in their lives, according to the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC).

Other than pain medication or surgeries for endometriosis, oral contraceptive pills are the most common treatment available for dysmenorrhea, according to an article published in the National Library of Medicine.

On average, 15.9 per cent of non-pregnant women aged 15 to 49 use oral contraceptives, according to Statistics Canada. The results also reveal that 53.9 per cent of women in the same age group report having formerly used the pill.

“[Women] often want a contraceptive effect and also an anti-acne effect,” said Claire Cogez, a nurse at the Centre de santé des femmes de Montréal (CSFM).

This was the case for Elizabeth Anits, a Concordia University undergraduate student in cellular and molecular biology, who started taking the pill at 17 years old.

“I had very bad acne and I was told it could help, but also [I took it] because I was in a relationship that was progressing,” she said.

However, neither Anits nor Paquet claimed they received an adequate explanation of the potential side effects of being on the pill.

“I don’t remember [the doctor] talking about the side effects,” Anits said.

“I wish that doctors or people that have the ability to prescribe it actually went into more detail for repercussions that it can actually have,” Paquet said.

Side effects and risks of birth control are numerous, including but not limited to headaches, nausea, bloating, increased blood pressure and blood clots.

However, Cogez said that one common misconception among people who take the pill is that skipping periods can be unsafe.

“It is a false belief that is very widespread,” Cogez said. “It is not toxic, [and] it is not dangerous.”

No concrete and reliable research to date suggests that skipping menstruation through hormonal birth control harms the body in any way.

“We impose things on women, we say that it is normal to have so many secondary effects. It is as if, as a woman, it is the price to pay if I do not want to have a pregnancy, so we internalize it a little and accept it.” — Claire Cogez, CSFM

Helpful and safe information regarding menstrual health remains available to people who may have experienced obstetric and gynecological violence. Services like the CSFM offer abortion services accessible to all women and also serve as a sexual and reproductive health clinic for women.

Cogez says that workers at the CSFM understand the reality of medical misogyny and tailor their services around it.

“[At the CSFM], we tend to do what we would have liked to receive, because we know it, we have all had negative experiences at a gynecological level,” Cogez said.

Concordia students also have access to contraceptive services.

“Students can learn about the various contraceptive options and obtain a prescription,” said Julie Fortier, deputy spokesperson for Concordia, in an email to The Link. “They can also get an intrauterine device (IUD) or contraceptive implant inserted, or get injections, if they choose one of these options.”

For Anits, having to take daily pills was challenging, which led to her making a switch.

“I hated the fact that every single day you had to do something for it,” Anits said. “If you missed today, you could be compromising your hormonal processes.”

It’s for these reasons that Anits decided to switch to a hormonal IUD, a T-shaped form of birth control that is inserted into the uterus and can last up to 10 years.

Despite their widespread use, hormonal contraceptives can have serious side effects. They are known to perpetuate depression or mood swings, according to an article published in the National Library of Medicine.

“My IUD [exaggerates my mood swings] because I don’t recall [having such] strong emotions before having an IUD,” Anits said.

Hormonal contraceptives are predominantly made for people with uteruses, with men only having access to condoms or vasectomies, according to a 2019 United Nations data booklet on contraceptive use.

According to Cogez, this can put a lot of pressure on women to have to take a form of protection in a relationship.

“We impose things on women, we say that it is normal to have so many secondary effects,” Cogez said. “It is as if, as a woman, it is the price to pay if I do not want to have a pregnancy, so we internalize it a little and accept it.”

There are new developments in male contraceptives like the implant Adam, or the hormone-free YCT-529 pill. According to a 2023 survey published in the journal Contraception, three-quarters of male respondents said they’d be willing to use new contraceptives.

Still, people such as Paquet and Anits expressed that they largely feel as though the existing systemic inequalities perpetuated by patriarchy have women worried as to whether cisgender men would take contraceptives.

“I think that it’s deeply rooted in patriarchy that women should be the ones to protect themselves and ‘close their legs’ in a way,” Paquet said.

Anits agrees, adding that this disproportionate role when it comes to contraception should be acknowledged.

“I think it’s important for [men] to understand what sacrifice their partners are making if they choose to take birth control,” Anits said.

This article originally appeared in Volume 46, Issue 4, published October 21, 2025.