Finding your true voice

Gender-affirming voice therapy is deeply empowering for trans individuals on their journey towards self-affirmation

I have forged myself a voice I cannot call mine. One I feel has lodged itself too far forward in my mouth, shaped by years of sex-specific vocal expectations forced on those assigned female at birth to sound quiet, unthreatening, unassertive and pleasant.

Ingrained from early childhood, it is our apology for existing and taking up space. Even as adults, before we can utter a full sentence, those sex-specific speech patterns have already betrayed us and stripped us of the authority and credibility routinely afforded to cisgender heterosexual men.

When I realized I did not share verbal and nonverbal cues commonly and instinctively used by cis men, an insidious grief settled in. It felt like I had not been handed the same script, and to avoid the spotlight, I was left to improvise this performance alone.

So, I altered my voice to blend in. After all, I had no idea who could help ease my voice dysphoria.

When I discovered gender-affirming voice therapy in an academic setting, I immediately knew I had found my professional calling. But I was also confronted with a harsh reality: public unawareness, combined with still-emerging literature, resulted in a cruel shortage of specialists, and made it nearly impossible for the public to access those specialized services.

Institutions, such as the Quebec government and academic bodies, must support, adequately fund and formally promote gender-affirming voice therapy, as it is a vital component of the inclusive healthcare system for which we strive.

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) are healthcare professionals who identify, diagnose and treat a wide range of communication disorders in people of all ages. Most people associate them with helping children’s and elderly people’s speech and language disorders.

However, in recent years, a new branch has emerged in the field of speech-language pathology: gender-affirming voice and communication therapy.

SLPs in this field help trans people feminize, masculinize or androgenize their voices, depending on their clients’ goals. For example, we may focus on articulation, pitch, resonance and loudness for people seeking a more feminine voice. This healthcare service is deeply personal, affirming and empowering for trans individuals on their journey towards self-affirmation and authentic expression.

However, due to insufficient promotion of the full scope of SLP work, marginalized populations often remain unaware of such available services until significant harm has occurred, resulting in missed opportunities for early prevention and intervention by SLPs.

Indeed, trans people regularly speaking in a voice either too high-pitched or too low-pitched for them are at risk of developing muscle tension dysphonia, a possibly chronic and painful vocal condition characterized by vocal strain. This disorder can cause one’s voice, among other things, to change in pitch, give out and become rough, hoarse and raspy. If left untreated, it may lead to permanent damage to the larynx or the vocal cords.

When combined with persistent psychological distress of voice dysphoria, the impact of one’s gender dysphoria can be severe. Considering the current right-leaning political environment as well, it is easy to see how those who need it the most remain unaware of this service.

Notwithstanding the current concerning rise in transphobia, as an SLP, I advocate for greater promotion of our profession, as early intervention and accessible healthcare are essential components of comprehensive care.

While trying to access this service, trans people face another hurdle: there are not enough specialists just yet.

In the United States, a 2020 study showed that only 8 per cent of SLPs surveyed reported having experience working with transgender individuals, while 20 per cent reported receiving training for working with those individuals.

In Quebec, such statistics remain unavailable. However, according to the Ordre des orthophonistes et audiologistes du Québec (OOAQ), around 50 SLPs attended an optional professional development course they offered in January 2024 on gender-affirming voice and communication therapy.

These low numbers reflect broader, underlying systemic issues: there is a significant gap in accessible, clinical and peer-reviewed material for both clients and SLPs; budding literature on trans individuals in speech-language pathology; and additional training required for SLPs to provide this service competently. The combination of these factors discourages many SLPs from specializing in this field.

As a result, trans people fall through the cracks of the system by never receiving the appropriate and specialized healthcare they seek.

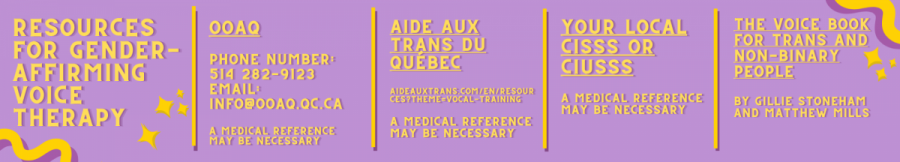

Gender-affirming voice and communication therapy rightfully belongs in the continuum of public healthcare services. Yet, due to a dearth of human, financial and intellectual resources, and with so few aware of the existence of this service, our work remains inaccessible for far too many trans people.

Communication is a human right; it is our gateway to socialization and self-expression. Amid a modern-day witch-hunt against trans individuals, our institutions must continue to recognize and invest in gender-affirming voice and communication therapy, through increased visibility, research funding and training.

There is a long way to go before this branch of speech-language pathology can truly flourish, and if we are to truly pride ourselves on having an inclusive healthcare system, we must stand behind both professionals providing this care and trans individuals seeking to discover their authentic voice.

Maxime Bourdon (he/him) is a master's student in speech-language pathology at the Université de Montréal.

This article originally appeared in Volume 46, Issue 4, published October 21, 2025.

_600_832_s.png)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)