Editorial: We Need Better Education on Aboriginal History

When a country like Canada calls itself multicultural, you expect the history classes in its elementary and secondary schools to be reflective of that diversity. And yet, the stories of Aboriginal Canadians are largely absent from the school curriculum and public discourse in most provinces, including Quebec.

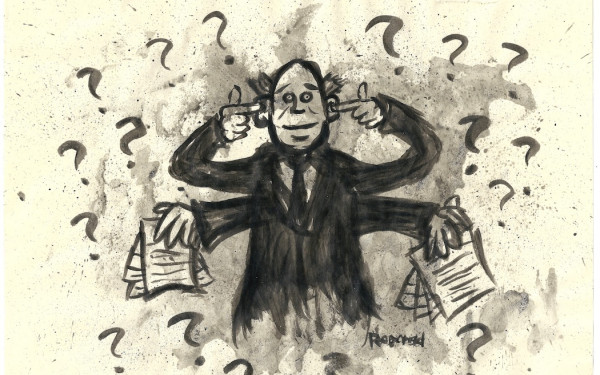

The consequence of overlooking First Peoples in history courses is that most Canadians are poorly informed about the historical context behind the present-day challenges that Aboriginal communities face. History must inform public policy if we want to better promote the social, political and economic development of indigenous communities.

To be fair, Quebec’s education reforms over the past decade have introduced some Aboriginal history into the curriculum. Grade nine students get a chronological overview of Canadian history, which begins with an exploration of the social and political organization of Aboriginal societies before European colonization in the 16th century. Meanwhile in Grade 10, students study history thematically through topics like historical power relations, including those between Aboriginal peoples and colonial authorities in the early days of colonization.

Post-colonial indigenous history, however, is severely lacking.

Once European historical figures like Samuel de Champlain, Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, James Wolfe and Sir John A. Macdonald come onto the scene, Aboriginal history falls by the wayside. This proves the Eurocentricity of the curriculum as European history supersedes the footnotes of indigenous histories.

With the exception of passing references to Manitoba’s founder and Métis political leader Louis Riel, we hear little about First Nations societies and the struggles of preserving Aboriginal culture and political autonomy in the face of a racist European colonial regime.

Little is taught about the Canadian government’s residential school system that sought to assimilate Aboriginal children and this policy’s lasting effects on Aboriginal identities, despite the fact that the last residential school closed less than twenty years ago in 1996. The work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which is studying the legacy of the residential schools, is ongoing and scheduled to end later this year.

In contrast, pages of Quebec history textbooks are dedicated to Eurocentric topics like Sir John A. Macdonald’s support for the construction of a transcontinental railway or the emergence of the social welfare state during Quebec’s Quiet Revolution.

Still there is hope that where our schools have failed, popular education is filling the gap. Aboriginal artists and student groups are generating dialogue through events and workshops such as First Voices week and panels such as “Aboriginal Territories in Digital Space” (see here).

For groups such as the Aboriginal Arts Research Group, revisiting history through video games designed by Aboriginal youth can help lead the way to telling more sincere stories.

For the First Voices week currently taking place at Concordia, the aim is raising awareness about contemporary issues. Discussions about indigenous learning systems through a living library of local elders and healers have been organized by the head of Concordia’s First Peoples Studies program, Karl Hele.

For us wary bystanders, participation means educating ourselves on a local level. While a recent Maclean’s article draws the nation’s attention to racism in Winnipeg—the urban centre with the largest Aboriginal population in the country—we shouldn’t forget our responsibility to hold our education systems accountable for ensuring a scrupulous education about how we’ve gotten to where we are today. After all, the legacy of colonialism and systemic discrimination is inescapable to this day.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)