Don’t waste your tears at home

Turning private grief into public display

Social media has transformed grief into a performance.

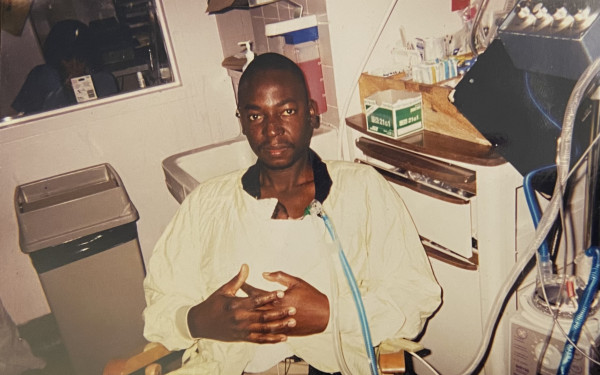

I know this because I’ve lived it. As someone who lost a parent as a teenager, the feeling of grief was unlike anything I had ever experienced before. I could view similar stories from people around the world that brought me comfort; they validated my emotions and helped me make sense of my pain.

But it also kept me trapped in it, feeding my tears and pulling me deeper into my pain.

The act of sharing incredibly intimate moments of your life for all to witness has become a norm that we can’t ignore. In the middle of a good crying session, we can set up a camera, hit record and post. We monetize our tears, removing the authenticity from what should be a sacred, chaotic moment of vulnerability.

Humans crave validation, and social media exploits this instinct. Sad music and dimmed lights are no longer private comforts—they’re staged for the camera in a performance of grief. When sadness is fetishized, it risks becoming a consumable aesthetic rather than a lived experience.

It seems like we aren’t just mourning, we are creating a brand through sorrow.

This commodification of pain is minimizing what should be a deeply human, often chaotic experience. Neither grief nor sadness is linear. Yet, individuals are expected to perform grief in ways that fit social media’s expectations: articulate, aesthetic and palatable enough to be consumed.

Still, performance and connection are not the same. Social media has completely reshaped the way we grieve. It gives us space to memorialize loved ones and feel less isolated in moments of sorrow. But this connection comes with the cost of exposure, making sadness public property.

The line between performance and sincerity is blurry. Is every moment of sadness performative, or do we just yearn for connection? How can we measure authenticity?

My own experience with grief and sadness exposes this paradox. My search for validation made me fall into the trap of measuring and comparing my pain to others.

This duality captures the truth of grieving online. It can heal and harm, connect and isolate. Social media can validate our deepest emotions, yet also turn them into a need for attention we endlessly crave from an audience. In the end, grief does not fit neatly into a feed. It resists curation—it is too chaotic to be filtered, branded or made palatable.

Loss demands to be felt in all its pain, and no number of likes can make it any easier to bear.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)