A trip to Palestine through art

Reviving Maroun Tomb’s artworks, long lost to displacement

For decades, Palestinians have grappled with memories of their homeland—or at least, what it could have been.

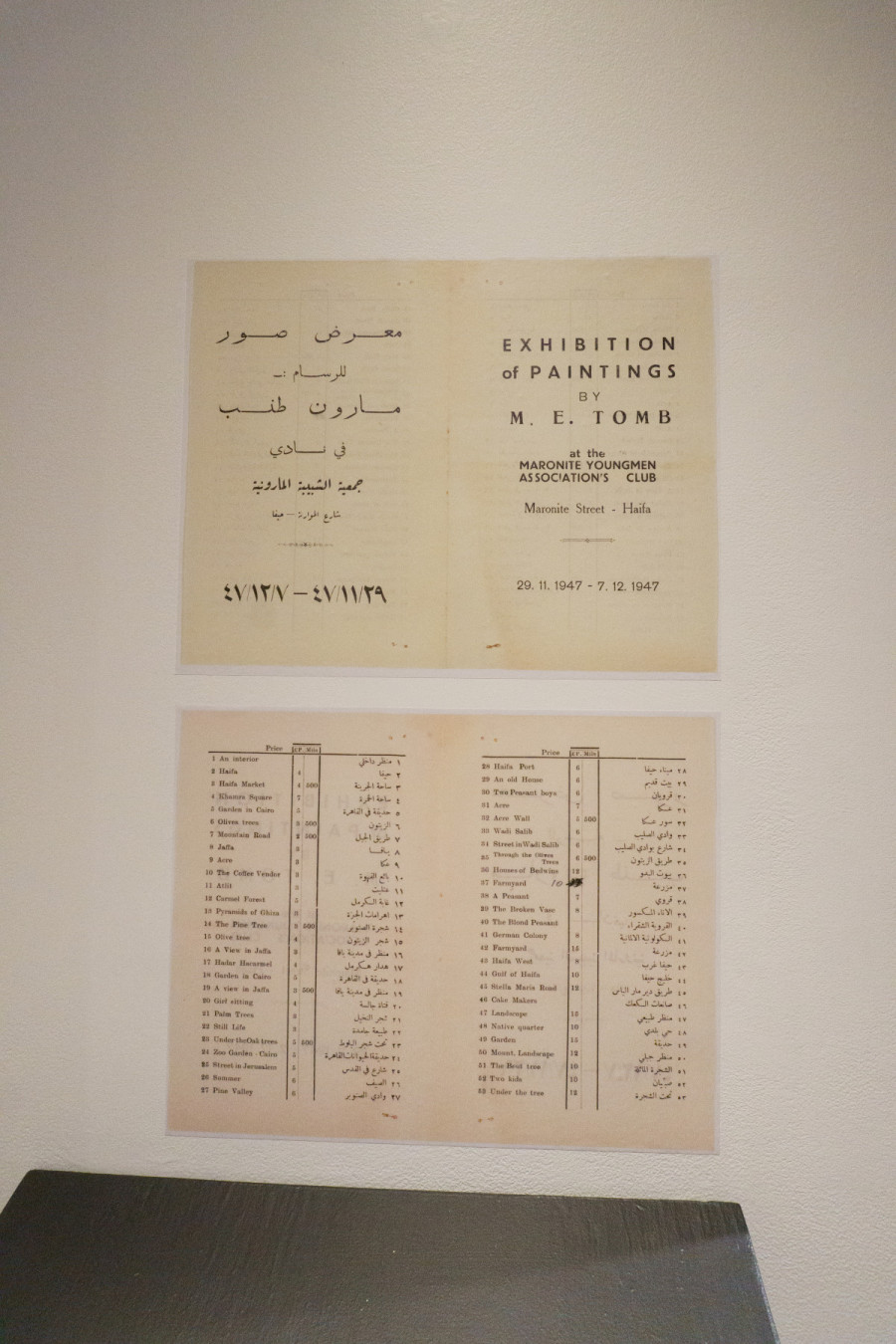

The MAI (Montréal, arts interculturels) opened its doors for the display of The Lost Paintings, a reimagining of the late Maroun Tomb’s last exhibition in Palestine, recreated by Palestinian artists from around the world. Tomb, a Palestinian-Lebanese artist, launched an exhibition featuring 53 oil paintings on Nov. 29, 1947, in Haifa, Palestine.

His opening coincided with the UN’s approval of the partition plan for Palestine, which triggered the Nakba. Known as "the catastrophe" in Arabic, the Nakba is a term used to reference the expulsion of over 750,000 Palestinians from their homeland between 1947 and 1949.

Soon after, Tomb and his family were forcibly exiled and never allowed to return. He lost his 53 paintings, along with most of his work before 1948.

Nevertheless, Tomb never stopped painting. His family’s displacement from Haifa led them to Lebanon, where he worked in Tripoli as the head of the art department at the Iraq Petroleum Company. Tomb later opened his own graphic design office in Beirut.

He passed away from a heart attack in 1981, just days before the planned opening of his 10th solo exhibition at Galerie Damo in Beirut.

The curators of The Lost Paintings—Joelle Tomb, Haidi Motola and Rula Khoury—have invested in this project for about three years. Joelle and Motola initially connected through Facebook after discovering that their grandfathers knew each other and belonged to the same group of artists in 1940s Palestine.

Joelle isTomb’s eldest grandchild. Only she and her sister had the chance to meet him. He passed away when she was two years old.

“I’m the only one who has a photograph with him, so somehow, I feel like it was destiny to start this process and meet Haidi,” she said. “Now I need to continue this. He continued his career until he passed away.”

Shortly after they connected, Motola’s grandfather passed away. While emptying his apartment, she came across archival material that became the foundation of this exhibition. Among them: an invitation letter for Tomb’s exhibition, written just months before he and his family were expelled.

Another archive revealed a document featuring the titles of Tomb’s 53 oil paintings, many of which referenced specific places in Palestine, specifically Haifa. This inspired a deeper reinterpretation of these sites.

“[The titles] make you think and imagine Palestine before ‘48,” Motola said. “[Artists] would imagine what Maroun Tomb saw when he was painting this, but also how they themselves see this thing.”

In 2023, after receiving a grant, Joelle and Motola invited Khoury to join the project. Khoury then reached out to many artists she knew would fit well for this exhibition.

Artists chose the title that resonated with them most from Tomb’s paintings and used it as inspiration for their work. They were also encouraged to bring their own family stories into this project.

Joelle, Motola and Khoury also sought to diversify the mediums represented for this project, inviting artists to submit photographs, documentaries, paintings, installations, sculptures and even a virtual reality experience.

“It was a combination of having some framework and direction, while also giving them some freedom to express in their own medium,” Joelle said. “[This diversity] adds layers of perspective, narratives and opinions. It’s a very rich way of interpreting what’s happening.”

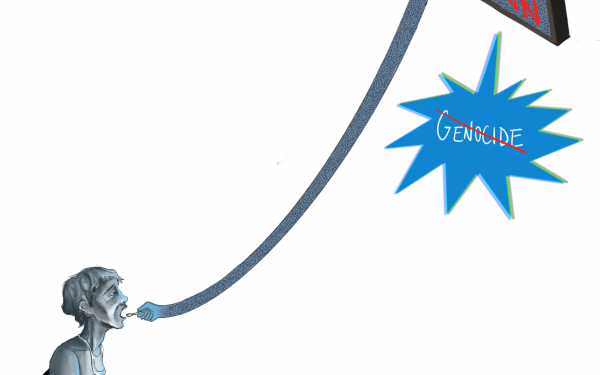

The process shifted after the start of Israel’s genocide against the people of Gaza in October 2023. Many of the works ultimately included direct response to the violence in Gaza.

“You can contest history, but you can’t contest personal narratives,” Joelle said.

“It’s the same feeling we had in ‘48. It’s similar to what Maroun Tomb had [experienced] in Haifa. It’s happening now again,” Khoury said.

Artists explored themes ranging from displacement to identity, memory and the power of imagination. Many pieces are coated with symbols related to Palestinian culture and history, including olive trees, oranges, landscapes and tatreez textiles.

One of the artists, Khaled Jarrar, created a piece confronting the brutal conditions Palestinian political prisoners are forced to endure in Israeli jails. His work showcases a set of prayer beads made of barbed wire, olive pits and rope.

As a child, Jarrar paid his neighbour a visit shortly after his release from jail. He noticed the man holding prayer beads made of olive pits that he had hidden and dried during his imprisonment.

This work alludes to the ways in which Palestinian prisoners find practices that enable them to express themselves despite the walls that constrain them, a testament to their resilience in the face of time.

Another piece that reflects a similar creative expression is by Raed Issa, an artist from Gaza who used charcoal and natural pigments from coffee, tea and hibiscus. His pieces document genocide, and the ones displayed are the only ones that survived.

“He continued painting while being displaced. He continued painting what he saw around him, using materials he could find,” Motola said. “In that way, he was also telling the story of what is happening right now.”

Motola also highlighted that the exhibition doesn’t just highlight the 53 lost paintings, but also symbolizes a larger loss and the ongoing colonial erasure of the Palestinian people.

“It’s very essential to be talking about ‘48, not as an event of the past, but an ongoing Nakba and connecting what is happening now to the loss that was back then,” Motola said.

One of the curators’ main objectives for The Lost Paintings was to facilitate connections between artists from all over the world and create an international platform in which they can discover new stories, as well as initiate dialogues rich in perspective.

For Joelle, art used as a powerful tool can give people a privileged position to discuss what they cannot resolve directly. She noted many pieces reflect the artists’ personal selves.

“You can contest history, but you can’t contest personal narratives,” Joelle said.

While Motola believes that art plays a major role in the building of lives and realities, and how they change through creation, envisionment and political imagination, it’s not the only tool at people’s disposal.

“Especially not in times of genocide. We still have to do other things as artists, like being in the streets and putting pressure [on the government],” Motola added.

Khoury sees art as a way of facilitating the understanding of Palestine’s history by spreading the information and elevating the voices of the artists.

“It’s also [a show of] solidarity with what’s happening,” Khoury said.

The exhibition will remain on display at MAI and the artist-run centre articule until Oct. 4.

This article originally appeared in Volume 46, Issue 3, published September 30, 2025.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)