Robert Fisk on the Middle East Crises, Canada’s Response

Understanding the Middle East and all its woes is a daunting, near impossible task.

Robert Fisk, a longstanding Middle East correspondent for The Independent, spoke at the St. James United Church Saturday evening to a large group of eager listeners in an attempt to impart his first-hand knowledge about the tumultuous region.

Fisk has been reporting on the Middle East for nearly 40 years. He has written numerous books, won countless awards for his work and has been recognized seven times as international journalist of the year by the British Press Awards. Notable past interviewees include Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and Osama bin Laden.

The event was organized by Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East and Solidarity for Palestinian Human Rights.

On Syrian Refugees and Canada’s Response

“You know, 20 to 30 years ago, in the Middle East, Canada’s reputation was absolutely, singularly identifiable,” Fisk said. “Canada helped those who suffered.”

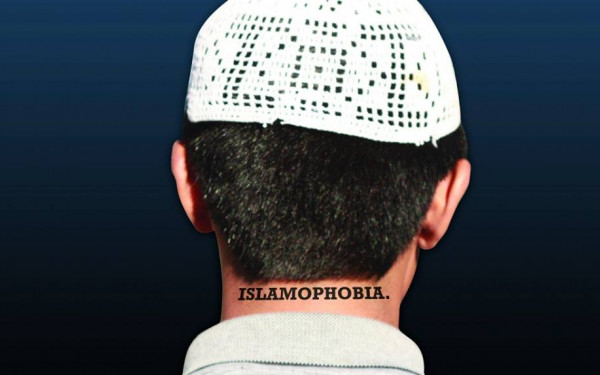

The rhetoric around the refugee crisis is one of fear, rather than compassion, Fisk mused.

“I’ve noticed over the past week and a half here, the way in which the narrative of the refugees has become constantly smeared with the words terror, terrorists and security,” he said.

“First of all, you must be frightened of those in your society who go to Syria and join ISIS, and then you must be frightened a few weeks later that they’re all coming back,” he continued. “I find this preposterous, but it’s something that’s worked its way into Canadian political dogma.”

Fear is an influential factor affecting Canada’s views of the refugee crisis. A recent poll taken by Ipsos revealed 71 per cent of voters believe “We can’t compromise Canada’s security, and individual Syrian refugees should go through proper screening to make sure they aren’t terrorists even if this slows down their admission to Canada.”

Underestimating the power of ISIS’s ideology would be imprudent, but the fact that we feel the need to closely examine every single incoming Syrian because we believe they might be Islamic State infiltrators demonstrates how seriously the rhetoric of fear has influenced our minds. Syrians are fleeing Syria because they too fear ISIS.

“One of the thing’s I’ve noticed is … politicians in this country seem to have fallen behind in their understanding of suffering,” Fisk said, comparing Canadian politicians to Canadian soldiers, who, in his view, are more compassionate towards refugees.

Nonetheless, a study conducted in July by ORB International shows that 21 per cent of Syrians believe the Islamic State has had a positive influence on Syria, in one way or another.

According to Fisk, it is a matter of restoring honour to our country. He admits that he doesn’t have an answer to the crisis, but believes that new institutions are needed to help hundreds of thousands of people escape from war.

Conservative measures would see 10,000 refugees settled by September 2016, Liberal measures would see 25,000 settled by January 2016, and the NDP would aim for 10,000 by the end of the year and 46,000 by 2019.

The West and The Middle East

According to Fisk, the story of the Middle East—which is a Western-centric name for west Asia—began with the division of land between France and England by means of the Sykes-Picot Agreement after World War I.

“Instead of giving freedom, dignity, independence [and] real lands, to anyone in the Middle East, we took them over,” he said. “Our forces went in, our military went in.”

He read the beginning of a letter that was written to the government of Iraq when England occupied Baghdad in the first world war. In the letter, the British declared themselves not as conquerors, but as liberators who were going to free the people from “generations of Tyranny.”

“So we’re always freeing the Arabs,” he said. “But we didn’t give them freedom from anything. We gave them more tyrants.”

Fisk called the countries in the Middle East our “experimental states.”

“We claimed we were giving a mandate to nurture them to understand how to run a country, and then we handed it over to dictators of our own; dictators who we paid, and armed to keep their people down,” he explained.

While covering the Arab Spring, Fisk noticed posters demanding democracy. The people in these countries viewed Western democracies as the forces that “paid and armed the dictators who repressed them.”

“What they asked for on the posters was dignity and justice,” he said. “This we did not intend to give them. Nor did we do so.”

ISIS As A Cold, Calculating Weapon

“What is this creature, ISIS?” Fisk asked.

The terror group uses more camera angles to film their heinous executions than Hollywood uses to film their motion pictures. They destroy great works of art with systematic precision, and show no emotion when slowly decapitating their victims.

“It took me a long time before I realized that ISIS is a weapon. It is a weapon with as little emotion and feeling as a [missile], or a [battleship]. It has no feelings. It has no emotions. It is empty, because it is a weapon,” he said.

“And the question, of course, is whose weapon is it?”

Without proof to back up his claims, Fisk said he believes ISIS is “an Arabian weapon from the gulf,” and he suspects that “the hand on that weapon is probably somewhere in Saudi Arabia or Qatar, or both.”

Stating that Saudi Arabia and ISIS dangerously “share precisely the same beliefs,” he claimed that funding for the Islamic State was coming from Qatar and Saudi Arabia. He didn’t specify that it was the governments of theses countries that were doing the funding, but that the money was nonetheless coming from those Gulf States, and possibly others.

_820_533_90.jpg)

1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpeg)