The Frac Job

Let’s Get Our Frac On

It’s not far-fetched to say that the massive Utica shale gas deposit found in the lowlands of Quebec is the best thing that ever happened to La Belle Province, given its fragile economic state.According to an official government document released on Mar. 31, 2010, Quebec had accumulated over $160 billion in debt while enjoying such perks as some of the lowest tuition rates and some of the best health care in the country.

If Quebec were a sovereign state, it’d have the fifth highest net debt compared to its gross domestic product in the world. In layman’s terms, Quebec is paying for more than it can buy, and its citizens are among the most indebted in the world.

Developing shale gas drilling will not only provide billions of dollars in royalties for the government, but also over 7,500 jobs to local residents. Quebec would also have enough gas resources left over to be able to export gas to countries where gas production is not a luxury.

Largely due to its discovery of oil and gas reserves in the 1960s, Norway now sports the third highest GDP per capita in the world. The Scandinavian country used funds gathered to develop the largest source of renewable energy in the Nordic region. Quebec now has a chance to do something similar.

Community concerns shouldn’t be written off, however—a few cases among the thousands of wells drilled in Alberta give the air around oil and gas exploration a bit of a rotten smell.

Citizens in Alberta have had an experience similar to Quebec’s when it comes to drilling and servicing companies. In Clearwater, AB, well servicing companies were looking to drill for sour gas—gases which contain significant amounts of hydrogen sulfide—which are highly poisonous and can be lethal upon first breath, depending on the density. Still, there have been no civilian deaths caused by sour gas extraction despite the thousands of wells that have been drilled.

In Quebec’s case, however, these aren’t sour gas wells that will be drilled, but “sweet” gas wells, the cleanest burning fossil fuel in the world.

A series of meetings concerning the environmental impact of hydraulic fracturing took place on Oct. 3, organized by the Bureau d’audiences publiques sur l’environnement, and a full report on the environmental effects is due in February. Environment Minister Pierre Arcand concluded that more stringent rules should be applied to companies wishing to perform exploratory drilling.

Furthermore, one of the main companies delving into exploratory shale drilling, Questerre, had released a fracking additive used in the controversial gas extracting method. Only 0.12 per cent of the fluid, which is used to create spaces in the shale, is made up of said additive, which, according to their press release, is made up of ingredients found in common, household products. The remaining 99.88 per cent of the frac fluid is made up of sand and water.

According to news reports, experts in the field say that this specific job does not put drinking water at high risk, since the fracking will take place thousands of metres below surface.

I commend the province of Quebec for demanding exploration companies to be more accountable for the environment, but the reality is that the province that’s most strapped for cash in Canada has just won the geological lotto and it’s afraid to cash in its ticket.

The answer to tuition increases, governmental perk, and more personal freedom lies beneath the reservoir and inside of that shale rock.

In order to maintain the standard of living Quebec boasts, fuel must be provided. It might as well be Quebec’s own fuel.

– Clay Hemmerich

Stop all the Fracking

Go and stick a match beside your tap water.What is going to happen? Probably nothing.

Now imagine being able to light your tap water on fire. For some residents of Colorado and Pennsylvania, tap water that bursts into a half-metre long flame is something they have had to learn to deal with.

Some residents of Quebec might soon share the same fate.

Despite the assurances of gas industry executives, gas wells dug into Quebec’s shale using high-volume horizontal slickwater fracturing, or fracking, carry a heavy risk.

It takes some explanation of how fracking works to understand the insanity of what is being proposed.

On the south shore of the St. Lawrence River between Quebec City and Montreal, oil companies from the United States and Western Canada want to extract natural gas from the Utica shale under Quebec.

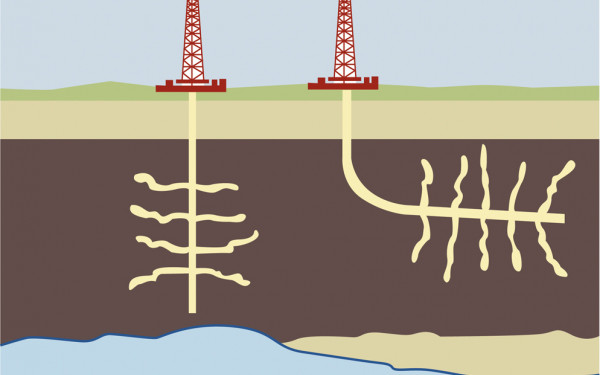

Shale is a very tight layer of rock about a quarter of a kilometre thick. In the shale, thousands of pockets of natural gas are trapped. With traditional drilling, getting to this gas would be impossible. That was until horizontal fracking was invented over a decade ago.

With fracking, a hole is dug down to a depth of 2.5 kilometres using traditional drilling. This involves piercing through the aquifer. Not to worry, says the oil industry: a cement tube is poured around the drill hole, protecting the aquifer.

At 2.5 kilometres deep, things get interesting.

The drilling goes horizontal and a tube is dug for about three kilometres through the shale. Explosives are then pushed down into the horizontal section of the drilling, blowing thousands of fractures into the shale. Into those fractures, a slurry of sand, water and “special ingredients” are then poured at high pressure, pushing into the shale and literally tearing it apart.

If the idea of “special ingredients” doesn’t worry you, it should. Up to now oil companies have not had to release what is inside their fracking slurry, claiming that it is a business secret. When fracking fluid was tested in the United States, benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene were found, all of which are hazardous to the health of living things.

Now you might wonder why Quebec’s drilling laws don’t require companies to release their ingredient list. The problem is, Quebec doesn’t have a drilling law. These companies are operating in a legal grey area and have decided to follow the province’s mining law.

Quebec’s mining law is currently undergoing a broad review after being considered the most business-friendly regulatory regime in the world for most of this decade. In the context of resource extraction, business-friendly often equates to minimal laws.

Operating with minimal oversight and pouring tonnes of dangerous chemicals through the province’s aquifers to shatter the shale rock that the aquifers rest on, the risks are largely undocumented and the only case to be made for shale gas exploitation is economic.

The industry will bring billions to Quebec’s government and provide thousands of jobs. However, the revenue needs to be placed in context.

The price of replacing the water from the province’s aquifers in the area where 90 per cent of Quebecers live is beyond billions.

This idea seems to reflect capitalism at its worst: reckless and aloof.

The idea of putting the tap water of five million people at risk for profit is beyond silly; it should be illegal.

-Justin Giovannetti

This article originally appeared in Volume 31, Issue 08, published October 5, 2010.