What the Frak?

Drilling for shale gas in Quebec’s St. Lawrence Valley has been put on hold.

On Oct. 4, Quebec’s environmental assessment board will host a public hearing and information session to discuss its investigation of hydraulic fracturing—the proposed method of gas extraction in the St. Lawrence Valley.

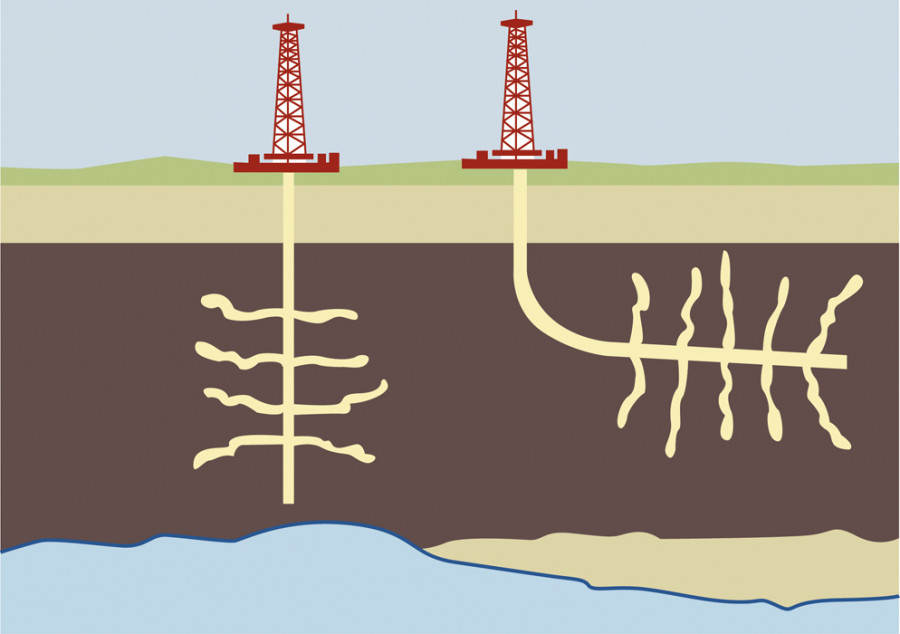

Hydraulic fracturing, or “fraking,” is a procedure that uses water, silica and chemical compounds piped several thousand meters below the earth’s surface, creating cracks in shale rock. This allows natural gas to be released and extracted.

The Bureau d’audiences publiques sur l’environnement is currently assessing the potential risks of further shale gas drilling in the Utica shale strata that run under Quebec.

In late August, the provincial government announced its intentions to open the St. Lawrence Valley to further fracking.

Environmental groups have since criticized the decision, claiming the project’s potential economic benefits are far outweighed by environmental dangers and concerns about public health.

The chemicals used in the procedure are a matter of contention. Several are known to be highly toxic—including benzene, which can be found in diesel fuel and is known to cause anemia and leukemia in humans. Other chemicals remain corporate secrets protected by intellectual property agreements.

Government bodies often require that companies divulge the contents of their fraking mix, but are sworn not to release the information to the public.

Several groups, including Equiterre and Greenpeace Quebec, have called for a moratorium on all exploration until the potential effects on ground water and soil can be studied. Stephen Guilbeault, the cofounder of Equiterre, stressed the need for an inquiry led by people outside the oil and gas industry.

“Obviously, the information provided needs to be independent,” said Guilbeault. “It cannot come from the people who stand to benefit millions from the exploitation of this resource.”

Danielle Hawey, the communications director for BAPE, would not comment on the makeup of the inquiry committee. When asked if members of the oil and gas industry would be a part of the review, Hawey stated that “the information will be released on [Oct. 4 and] the commission has already begun its investigation.”

Some politicians argued that a potential financial boon from the drilling, in a time of rising concerns over energy security, could reshape the landscape of energy production in Canada.

Nathalie Normandeau, Quebec’s Natural Resource minister, has said that shale gas is an opportunity to reduce the province’s dependency on Alberta. Quebec currently imports most of its natural gas from the West.

Normandeau sees this as an opportunity to “consume a natural gas that is 100 per cent from Quebec,” and to provide thousands of jobs.

Andre Caille, the president of the Quebec Oil and Gas Association, spent the past several weeks hosting information sessions in areas known to be currently under exploration, claiming that Quebec

is blessed with this chance to reduce its reliance on gas from Alberta.

Concerns have been raised by those opposed to the expansion about the massive quantities of water used in the procedure and the disposal of contaminated water left over from the extraction process, also known as brine. About 40 per cent of the water used in the procedure can be recovered and reused after water treatment.

The remaining water and chemicals remain in the rock formation below.

Geraint Lloyd, geophysicist and independent consultant on drilling within the St. Lawrence Valley, said that due to an incredibly high water-to-chemical ratio, the depth of drilling and the non-porous nature of the shale rock, there should be little worry about contamination.

“The higher the toxicity levels the more expensive it is to treat,” said Lloyd. “No company wants that. By the time they remove the water from the pipeline it has less chlorates than Montreal’s tap water.”

At each step of the drilling procedure, concrete is fed into the well, creating a seal meant to separate the pipeline and its contents from the soil and the groundwater aquifer—an underground layer of porous-rock from which potable water can extracted.

Contamination of the aquifer is the chief concern of many living in the valley, but Lloyd stresses the procedure is designed to maintain pressure within the pipeline and can only work efficiently with a proper seal.

“Any sort of failure or contamination issue comes down to engineers, not the procedure. With the high safety standards in Quebec, I can’t see this being an issue,” he said.

There have been several cases where fraking has resulted in environmental damage and water contamination. Thousands of complaints have been lodged throughout New Mexico, Ohio and Pennsylvania, where thousands of wells have been drilled using hydraulic fracturing. Samples there have shown benzene concentrations in the groundwater that are several thousand times higher than what is considered safe for human consumption.

Green Party water critic Lorraine Banville recently cited the experience in the U.S. as proof that fraking is unsafe.

“We only have to look to our neighbours to the south to see the problems,” she said. “In Pennsylvania, Wyoming and Colorado, this type of gas exploration has been disastrous and legislators are now trying to clean up the mess after the fact with very strong regulations.”

In New York, there is a temporary ban on natural gas extraction. Government officials cited a need for further study of the potential dangers of the process as the reason for the ban.

Critics of the ban argue that this potential revenue stream must be exploited.

Officials from New York City and environmental advocates argue that the United States’ most populous city, which receives some five billion liters of water a day from unfiltered reservoirs—some of which are connected to the Marcellus gas patches of Pennsylvania—cannot be too cautious.

According to Global Data, 27 wells have been drilled in the St. Laurent Valley, with no prior consultation.

All production has been halted in the St. Lawrence Valley pending the provincial investigation.

This article originally appeared in Volume 31, Issue 07, published September 28, 2010.

__600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)