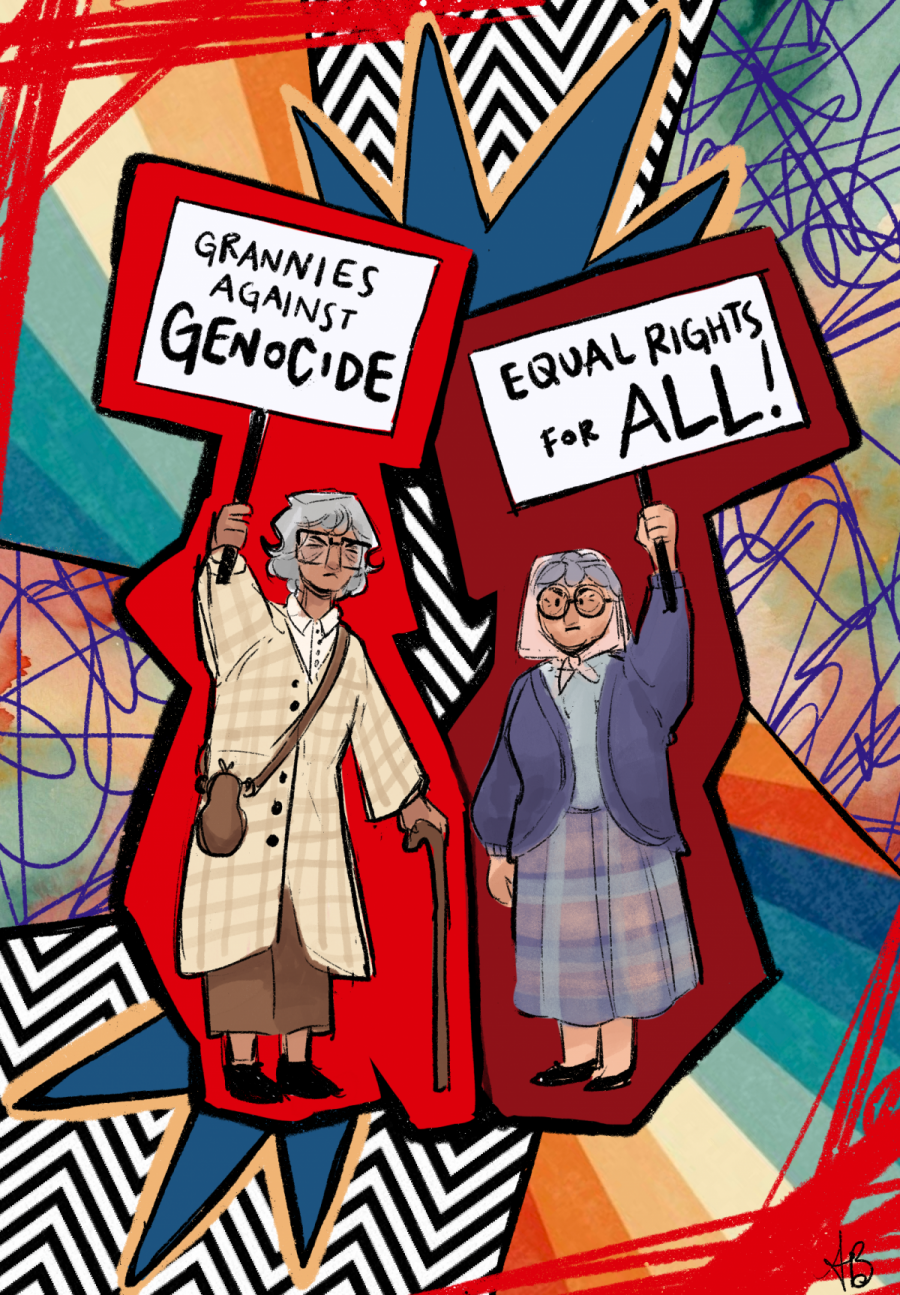

Speak up, grannies!

In metros and in the streets, Montreal’s older women activists are fighting for peace

In a bustling metro station, I am on a mission to find RoseMary Whalley—an 82-year-old anti-war activist.

A few months ago, I briefly interviewed her for a radio show about her decades of activism. Her story stuck with me—I wanted to know more.

Amongst the sea of people, I recognize her by her little stature and purple hat. There she is, leaning on her cane and reading a book.

To the naked eye, she may just look like any other older woman.

But she is full of stories.

Whalley has been protesting against the use of nuclear weapons for nearly seven decades. At just 14 years old, she was marching the streets of England for the Ban the Bomb movement every weekend.

“A lot of people go to parties when they're young,” Whalley says, “but I went to demos.”

After we walk up and down St. Denis St., she takes me to this quaint vegan buffet.

“I’ve been [protesting] for a hell of a long time,” she says, taking a bite of her food.

After over six decades of protesting outside grocery stores and marching in the streets, Whalley’s energy may be worn—but her spirit isn’t.

She hands out flyers about Canada’s complacency with the war in Gaza three times a week at different metro stations with two other older women.

One of these women, Laurel Thompson, is considered by Whalley to be “the boss” of the group. Thompson is 88 years old, but fierce as ever.

Many of the older women activists we see marching the streets today were once the courageous young activists of the '60s.

They are fighting the fight decades later, but this time with greyer hair, slower steps and more wisdom.

They are called the silent generation, but they are pretty loud about social justice. In 2018, 32 per cent of elders from the silent generation volunteered in some form of activism, averaging 222 hours a year, according to Statistics Canada.

After retirement, older women who are passionate about social justice have been dedicating their time to using their voice for change.

For Whalley and Thompson, this passion of theirs has only grown stronger since they first started protesting in the '60s—the era of revolution.

The student movements of this time came together in protest against the Vietnam War, and for environmental issues, the women’s rights movement, civil rights and gay rights.

At the time, Whalley focused her activism on opposing war and banning nuclear weapons.

“I grew up knowing the horrors of war,” Whalley says, her eyes turning red and teary, “so doing activism is a no-brainer.”

Genocide and war are not unfamiliar subjects in Whalley’s family.

Many of her family members were murdered in concentration camps, including her grandmother.

Her mother, a Holocaust survivor, fled Berlin, where she met Whalley’s father in England—a British soldier who fought in one of the most violent battles of World War I, the Battle of the Somme.

This family history shaped her worldview and fuels her urgency today.

In today’s political climate, particularly with the ongoing genocide in Palestine, she feels it is her duty to speak out now, perhaps more than ever.

Whalley has never been in a situation where so many people have come together in opposition for a long period like this.

“Mind you, I’ve never seen a genocide like this,” she says. “This is the worst thing that’s ever happened in my life.”

Thompson shares this passion.

During a phone interview, Thompson tells me she has been involved in activism since the Vietnam War, when she was 22 and a student at York University in Toronto.

“As I got older and started to be an independent woman, I just saw stuff that I knew was not right,” Thompson says, “I knew I wanted to fix it—or try to fix it.”

At the metro station, Thompson boldly talks back to an officer who tries to stop them from giving out flyers.

“He’s full of himself and thinks he's a hotshot, and is going to tell these women to shut up,” Thompson says, turning to us.

“Fuck you,” she whispered, flipping them off.

I was surprised by her vigour. This feistiness has stuck with her since she was in her 20s.

When I asked Thompson about being an older woman activist, she told me it feels the same as it did when she was 22.

“You made me realize I think I’m younger than I am,” she says with a chuckle.

Back at the restaurant, Whalley tells me about the privilege of being an older woman activist.

She says older women’s presumed innocence and fragility allow them to get away with more shenanigans, without the violent repercussions that the younger generation could not.

“It would take a really inhumane cop to beat the shit out of somebody like me,” Whalley says.

I ask her if she’s been harassed by the police before.

”I’ve been arrested a few times,” Whalley says, chewing her noodles casually. “It’s not important—I haven’t been arrested enough.”

Whalley and Thompson are not the only older women activists standing up against human rights abuses in the city today.

One other group—or gaggle, as they say—that is well-loved across North America is the Raging Grannies.

You might catch this large group of older women wearing grandma-like clothing—long skirts, aprons, shawls draped over their shoulders and funky hats with activism-related badges and buttons—and brashly singing “fuck the government” versions of classic tunes.

Sheila Laursen, an 80-year-old Montreal Raging Granny, has been raging since 2010.

At a no-screen cafe, she tells me about what it means to be a Granny. As Laursen explains, it all started with the Victoria Grannies in 1987.

“They were outrageous,” Laursen says. She liked their whole idea. The performative art of activism.

After retiring from the YMCA, she knew her destiny was to be a loud social activist.

We sip our coffees and pick at our scones, while she shows me the heavy pile of Raging Granny newspaper archives dating back to the 90s.

For decades, these bold older women have been raging about climate change, national politics, Indigenous rights, women’s rights and anti-war across Canada and, more recently, the United States.

These women have dedicated years of their lives to social justice, yet they are still fighting the same fight Whalley admits.

“In the late '60s there was an upsurge of young people who didn't like the way things were, and decided they wanted to change it,” Thompson says, “and the same thing is happening now.”

She says that because of social media, Gen Z is awake to “what the West does” and its complicity in war and genocide.

They choose to continuously fight alongside the younger generation today, in hopes of the future they waited for all those years ago.

“As long as I’m able to walk and talk,” Thompson says, “I’ll be fighting for peace.”

This article originally appeared in Volume 46, Issue 1, published September 2, 2025.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_(1)_600_375_s_c1.png)