Get a Room!

Visual Artist Marie-Eve Martel Uses Poetry and Philosophy to Analyze the Architecture of Spaces and Places of Knowledge

In a dialogue between architecture, poetry and philosophy, visual artist Marie-Eve Martel presents an immersive installation entitled Transcender l’architecture, depicting the duality of two architectural environments—Thoreau’s cabin in the woods and Yale University’s Beinecke Library in New Haven.

Clinical and sharp, the white gridded walls of the gallery’s first room bounce off the bright lighting, which is directed towards a white monochrome miniature model of the Beinecke Library, standing erect on a podium in the center of the space.

“When I first saw the original building, I had the same feeling the humans must have had when they discovered the big black monolith on the moon in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. It was really mysterious and the feeling stuck with me. I wanted my piece to illustrate that impression,” said Martel.

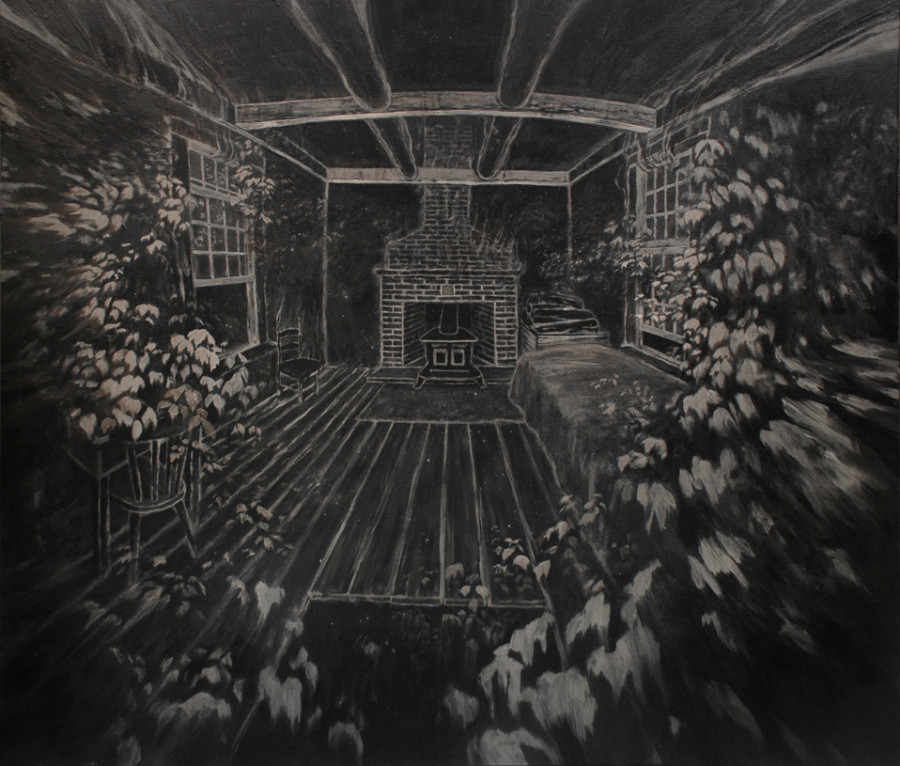

An oval opening in the wall marks the entrance to another room—the stark opposite of the first, with black painted walls and dim lighting. With quotes from Henry David Thoreau’s 1845 book Walden handwritten with chalk on the walls, the atmosphere becomes one of poetry and nature. A series of paintings depict the cabin in the woods becoming gradually invaded by vegetation, turning into a micro universe. A radically different space of knowledge is represented here—a dream-like space in which one learns through contact with nature and introspection.

On one side, a space for knowledge is represented through a clean, controlled and imposing piece of architecture; on the other, Martel creates a metaphor for the exploration of one’s infinite nature. In contrasting ways, both environments reflect the psychological impact of physical structures, questioning the different ways we inhabit and interact with our built environment.

“The black is more attuned to the feeling that I had when I read Thoreau because it’s so much about looking inside yourself to find yourself,” Martel said. “He wasn’t an antisocial person, not at all. He loved people, loved talking to people, but the retreat and the contact with nature is really crucial in the process of knowing who you are and getting in contact with your true self.”

Containing some of the world’s most precious manuscripts, the Beinecke Library is a highly secured and controlled building. Symbolizing both knowledge and institutionalized power, the building is at the heart of an interesting paradox that Martel seeks to underline in her representation of the building.

The accessibility of knowledge is at the centre of the problem. As Martel explained, the library’s books are exclusively reserved for university students and researchers. An entire procedure and protocol has to be followed to be able to look at the documents. In an attempt to preserve the rich knowledge kept within this “sacred safe”, this type of control simultaneously protects precious resources and limits free circulation of ideas.

“The whole emotional aura of the building is what got me working on that piece in parallel to Thoreau’s cabin, which is kind of the opposite [of it]. But at the same time, some aspects link them together because both represent a form of access to knowledge,” Martel said.

With thoughts nourished by philosophers such as Henri Lefebvre, Michel de Certeau and Michel Foucault, Martel’s art practice puts forward certain concepts brought upon by theories around the relationship between space, built environment and socio-political order.

“Everything that is built around us has to do with the power in place. It’s just the way societies are constructed. Everything that is built, from the university here to a barn in the country, has to do with the values that had them built. Architecture is a way for humankind to manifest its values into space.”

Paralleling Michel Foucault’s discourse on heterotopias—spaces with layered meanings that are meant to make utopias possible—the library is, as Martel underlined, a kind of modern-day utopia that aims to preserve knowledge in its entirety. But in doing so, the library’s structures are made impermeable to nature, cut off from processes and contingencies of natural decay.

Nature is presented as a force that infiltrates or is—in the case of the Beinecke Library—absent from iconic architecture. Quoting Thoreau, Martel adds that the philosophy behind the wooden cabin is in itself the complete opposite of the philosophy behind Yale’s Library. Central to Thoreau’s piece is the idea that absolute control is impossible and the need for the human being to be in contact with nature is essential to the learning process.

“If you look at private universities and private libraries, they are inaccessible to the broad public and then it becomes a symbol of power, elitism, state control and then there is a negation of nature in that,” said Martel.

Leaving the dialogue open between the two different spaces, Martel challenges different layers of meaning and creates a poetic language, putting a strong emphasis on sensory representations.

Transcender l’Architecture // Jan. 9 to Feb. 21, 2015 // Galerie de L’UQAM (1400 Berri Street, Judith-Jasmin Pavilion, Room J-R120) // Free

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_s_c1.png)