Your TikTok algorithm is not your friend

Scrolling through a sea of videos, political agendas can covertly manipulate perceptions of reality

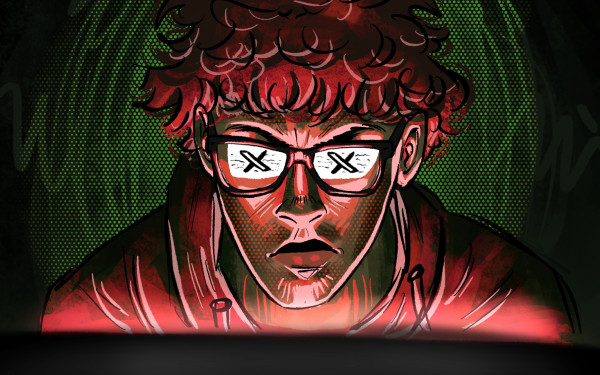

Excessive doomscrolling—the self-destructive habit of obsessively searching the internet for distressing information—is increasingly common in younger generations.

According to a McAfee study, the pandemic shaped the doomscrolling habits of 70 per cent of 18 to 35-year-olds worldwide in 2023.

Tristan Harris, a former design ethicist for Google who was featured in The Social Dilemma, argues that social media platforms in general have been developed to emulate addictive experiences, similar to gambling. However, TikTok’s algorithm specifically has been considered particularly cutting-edge by publications like the MIT Technology Review in 2021.

TikToks that appear on a user’s For You page are based on content more than popularity. This means that a post’s tags, title and used audio are all prioritized over the size of a creator’s following.

Meanwhile, collaborative filtering—the process of users being shown TikToks similar to others they have interacted with—paired with a user’s in-app activity provides TikTok with the extra data necessary to get a full picture of each user.

The content that comes out of this process is ultra-tailored to each user. The TikTok algorithm’s purpose, however, is the same as other platforms’ end goal.

“What's most important for them is that people just stay on the platform because they are for-profit businesses, their revenue stream comes from the advertising and the sponsored content on the platforms,” media researcher Stephen Monteiro told The Link. “[TikTok] doesn't really care what the potential harms of that content are because the machine is built to keep people's attention and keep people on the platform.”

Jerome Anderson, a man in his early 30s who has been granted a pseudonym for safety reasons, said he saw similarities between how YouTube and TikTok algorithms work.

Anderson began watching videos on atheism around 2016 from YouTubers who, after garnering a large audience of young men susceptible to feelings of inferiority, shifted their content to centre around anti-feminism.

“When you watch enough caricatures of people that evoke anger or fear within you, you start losing your grip on reality,” Anderson said. “Your brain starts to search for reasons why these videos evoke anger in you. This is when you become susceptible to narratives.”

Similarly, other cognitive biases push people to prioritize information from individuals and news organizations that they already tend to like and agree with.

In a 2023 study, Siyao Chen, a student studying media, culture and society at the University of Glasgow in the U.K., used TikTok as a case study in his research on “filter bubbles.” The filter bubbles phenomenon describes how personalized algorithmic recommendations can limit exposures to wider ranges of information and may lead to stereotypical viewpoints and biases.

Chen found that TikTok creates filter bubbles that lock users into an “echo chamber,” where users are limited to a specific range of information that aligns with their worldview.

In the Scientific American article, “Information Overload Helps Fake News Spread, and Social Media Knows It,” researchers Filippo Menczer and Thomas Hills discuss their joint study on social media. The researchers found that when people get used to hyper-personalized social media feeds, they can fall into the habit of unfollowing and ignoring content that clashes with their worldview.

According to Statistics Canada, social media has become the main news source for 62 per cent of Canadians aged 15 to 24.

Media scholar Ethan Zuckerman wrote in a blog on Medium that the legacy media system has been disrupted as people can now voice their opinions online and share the news themselves instead of relying on distributors.

So long as they generate enough engagement, content from news outlets, or reactions to them, can be sandwiched between other types of content in people’s feeds. This landscape makes sensationalism an economical solution for some, according to a study by communication researchers Salman Khawar and Mark Boukes of the University of Amsterdam.

“It's my experience that most headlines are deceptive or misleading when compared to the actual story,” said Concordia communication studies part-time faculty Ken Briscoe. “The headline's function is not as clickbait but rather it is meant to [...] summarize the story simply and completely."

Menczer and Hills found that information from social media posts generally only reaches users when their data tells the algorithm that it fits into their preferences. Information outside this category, on the other hand, is less likely to find users, limiting their ability to understand topics beyond their original viewpoints.

They also note that the large bulk of content available online makes users extremely prone to spreading non-factual information, as algorithms only show them a fraction of what is out there.

Although researchers have found that misinformation exists on all sides of the political spectrum, another study by Petter Törnberg and Juliana Chueri found that its rise benefited the populist far-right more than other orientations.

For TikTok specifically, Queen’s University scholar Vincent Boucher stated that watching a lot of “moderately conservative” videos eventually leads users down a rabbit hole of increasingly radical content. This phenomenon is due to the creation of echo chambers as groupthink leads to more moderate views being reinforced and then radicalized.

While Zuckerman pointed out that polarization is a gold mine for engagement, other scholars such as Gabriel Weimann and Natalie Masri have expressed that TikTok does not appear to be fully enforcing its guidelines for hateful conduct.

“For the platforms, what's of primary importance is keeping people engaged and using the platform and the products that are on the platform,” Monteiro said, “and even if that means feeding people content that is harmful either to themselves or potentially harmful to society. That's, at best, a secondary concern.”

This article originally appeared in Volume 45, Issue 11, published March 18, 2025.