Memories In Structures

MIT Professor Speaks at Concordia About the Importance of Cultural Architecture in Eastern Europe

When you think of Eastern Europe, chances are the first things that come to mind are communism, corruption and poverty.

MIT professor Azra Aksamija is looking to add architecture to that list.

An architectural historian and artist, Aksamija will be giving a lecture this week as part of the Conversations in Contemporary Art series at Concordia, presenting her work on issues of cultural identity construction through art and architecture.

A native of Bosnia and Herzevogina, which serves as the grounds for her work, Aksamija concentrates her effort on providing context for those unfamiliar with the country and its former Eastern Bloc neighbours.

“I felt that the fact that I had survived [the Bosnian War], and managed to have this rescue, move to Austria and have this education in America—I found it was my obligation to give something back,” she said.

Aksamija’s work investigates the role of religious architecture, specifically the mosque, as a space where culture is constructed and how it can therefore sometimes act as a barrier against nationalistic propaganda.

One of the periods she focuses on is the early 1990s, when post-socialist Yugoslavia was plunged into war, with strife and divisions between different ethnic groups of Muslims at a devastating high.

“In the case of Bosnia [then a part of Yugoslavia], you have 70 per cent of Islamic religious architecture being systematically destroyed [in the war],” said Aksamija. “Buildings were destroyed to such an extent that they were completely bulldozed—foundation stones were partly dug out and carried to unknown locations so that you cannot rebuild from the original.”

Destruction of buildings is often unavoidable in war, but Aksamija’s work delves deeper into how methodical demolitions can actually be a part of a broader campaign of identity erasure.

“Any type of architectural structure marks a spot where a certain community has been living—it’s material evidence of that specific group’s existence,” she said.

“In our war, [the structures] were targeted because they marked the history of a certain group to a certain area and their historic claim to a specific land, and as such, they stood in the way of nationalists and genociders.”

As a way to understand the post-war identities and tensions still existing in Bosnia today, Aksamija gives a closer look at how and why mosques become identity markers for Bosnian Muslims, and how they fit into broader questions of history and art.

“A lot of my work is about cultural mediation and basically trying to express, in a respectful way, cultural differences,” she said.

“I try and restore some of those memories of collective life that the ethnic cleansers and genociders want to erase.” —Azra Aksamija, MIT professor

Mosquerade

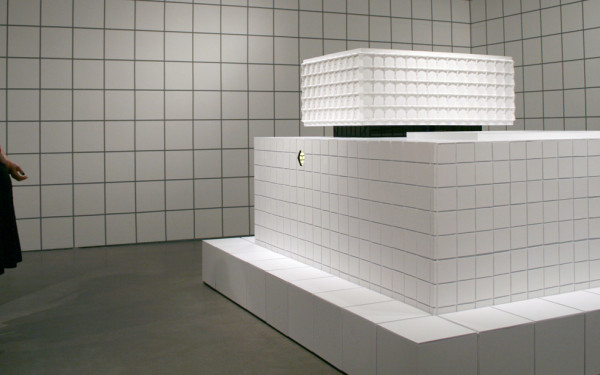

Through clothing, architecture and other cultural-religious symbols, Aksamija uses a cultural pedagogy approach to unearth the truths of how art comes to construct what makes us who we are. Wearable Mosques is a project of hers that looks at how architecture tends to transcend simply the buildings we build, and the way that those places tend to incubate, reinforce and represent our identities.

Aksamija says the project is meant to “deconstruct prejudices but also to be critical in many different directions towards different ways of constructing Islamic identity in the world.”

The idea is to show Islamic identity as “local, individual” rather than monolithic. Architecture, in this way, becomes a process of not only construction, but also deconstruction, where community and individual identities are built and re-built following conflict.

In addition to her work on mosques, Aksamija has studied the ways cultural institutions affect a community—not just the buildings but what’s inside of them, as well.

Over the past year, she has headed the Day of Museum Solidarity campaign in response to the shutdown of the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The museum was closed in 2012 after 124 years of existence, preventing access to valuable items related to Bosnian cultural heritage.

Working with a variety of international collaborators, scholars, artists, museologists and librarians, Aksamija founded a website last January in response called Cultural Shutdown. It aims to raise awareness about the political impasses that limit access to items of artistic and historical importance and, perhaps more importantly, to the collective memories of peace and cooperation that such items represent.

As a part of the project, museums were asked to cross out one work of art in their collection using yellow barricade tape with the words “culture shutdown” emblazoned across. More than 225 cultural institutions have since taken part. Aksamija founded the project with the idea of “restorative memory” in mind.

“Museums house memories of co-existence, the history of Bosnia as a place where many cultures have met and lived together,” she said. “So restorative memory means to basically try and restore some of those memories of collective life that the ethnic cleansers and genociders want to erase.”

Azra Aksamija // Nov. 7 // VA-114 (1395 René Lévesque Blvd. W.) // 6 p.m. // Free admission