Fat bodies, discipline and the politics of size

Wellness culture and fascism collide in their obsession with discipline and correction

Fascist and authoritarian regimes have always been obsessed with order, discipline and control, including control over bodies.

Power isn’t just brute force; it’s ingrained in people, convincing them to self-regulate, to shrink, to accept that deviation must be corrected. The "proper" body must be contained, obedient and small.

And fatness?

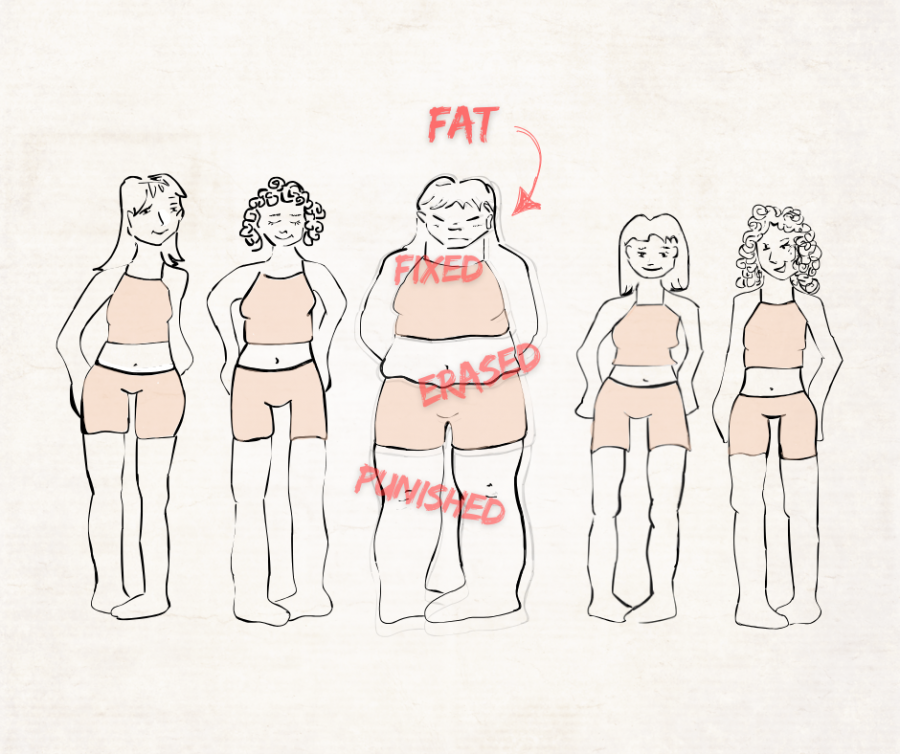

Fatness is disorderly. It resists containment. It must be fixed, punished, erased.

This is why fat bodies have always been policed, whether socially, medically or politically. In a world obsessed with discipline and efficiency, a fat body is seen as failure. It is undisciplined.

A fat body, like brightly dyed hair, piercings or extravagant outfits, is an act of defiance. If the system wants to flatten everyone into one acceptable version of humanity, then my body itself is resistant.

Simply existing in a fat body is seen as a statement.

Sometimes, I wish it weren’t. I wish I didn’t have to justify myself, or base my worth on proving that I’m trying. I don’t owe anyone that. I don’t owe anyone confidence. I don’t owe anyone some quirky fat-person self-acceptance that makes others comfortable.

The fixation on controlling fat bodies is clear: exercise isn’t framed as something you can do, but something you must do. It’s treated as a moral obligation, to yourself, your family, your future partner.

Think about that—your body, your choices, your entire lifestyle are reduced to an obligation, not a personal decision.

But the need to control bodies is not new. It is embedded in the very tools used to define health. The Body Mass Index (BMI), developed in the 19th century by Belgian statistician Adolphe Quetelet, was never meant to measure individual health.

Rooted in studies of white European bodies, BMI disregards racial diversity, labelling non-white bodies as unhealthy. Despite being discredited, it still shapes public perception, enforcing narrow, Eurocentric standards.

This is not about health, it is about control. Fascist regimes have long tied bodily conformity to discipline, framing deviation as weakness. BMI does the same, disguising compliance as self-improvement.

To these systems, a “proper body” is a controlled body.

Another ridiculous example is the 2019 Nike mannequin controversy, when critics slammed the brand for displaying a plus-size mannequin, claiming it promoted obesity.

If you claim to want bigger bodies to exercise, why did that mannequin anger you? Why does the mere presence of a larger athletic body in a sports store threaten you? As if we don’t need or deserve athletic attire. As if a fat body in motion cannot be fathomed.

This is where fascism and fitness culture collide: there is a correct way to look, a correct way to move, a correct way to be. And if you refuse to comply, you will be punished.

This is especially clear when celebrities lose weight. When Lizzo, who has spent years being mocked, ridiculed and harassed for her size, posts about her weight loss, her comments flood with relief. When supermodel Ashley Graham did the same, people thanked God she finally came to her senses and stopped “wasting” her beauty.

The expectation is that, given enough time and pressure, fat people will eventually correct themselves. There is no room for neutrality. You’re either an inspiring success story, a cautionary tale or a punchline.

Fascism thrives on this logic.

It justifies control under the guise of improvement, of efficiency, of making society better through discipline and restriction. And fat bodies, simply by existing, disrupt that illusion.

A fat body says no. No to control, no to constant self-surveillance, no to the idea that we must be smaller to be worthy.

This article originally appeared in Volume 45, Issue 11, published March 18, 2025.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)