Concordia draws outcry over decision to cut limited-term teaching positions

Faculty in precarious roles say they feel betrayed as the university moves to trim $1 million from steep deficit

The start of November has been marked by grief, outrage and betrayal, shared several Concordia University faculty members. Word has spread quickly that the administration will not renew any limited-term teaching contracts next year.

“I felt like a school kid getting expelled,” said limited-term English professor Reza Taher-Kermani, describing the afternoon he received the news. “The university is tossing us off, throwing us like garbage.”

According to the university, the decision comes as part of efforts to stay within its approved deficit target of $31.6 million for fiscal year 2025-26. Back in May, president Graham Carr said in a statement that the shortfall could reach $84 million without any intervention.

For limited-term classics professor Lauren Kaplow, the news arrived during class via email.

“My students were taking an exam, and I was supervising the exam,” Kaplow said. “I was really upset.”

The devil’s in the details

Limited-term appointments (LTAs) are contract positions with a fixed end date, often one year in length, and no guarantee of renewal or consideration for tenure, according to the collective agreement signed between the Concordia University Faculty Association (CUFA) and the university in 2023.

Anna Sheftel, principal and professor of Concordia’s School of Community and Public Affairs, calls the timing of the cancellations “particularly cruel.” Sheftel was under the impression that next year would be the first year LTAs could apply to convert their positions into extended-term appointments (ETAs), positions that offer renewable terms and greater job security under the collective agreement.

The collective agreement stipulates that if the provost approves a department’s LTA “for four consecutive years to respond to the same specific teaching needs [...] and the positions are filled in each of the first three years,” then in the fourth year, “the limited-term position shall be allocated as an extended-term position.”

If the countdown began in the 2023-24 academic year, following the ratification of the agreement, the fourth year would come next year, in 2026-27. Concordia’s deputy spokesperson Julie Fortier, however, said the agreed timeline for conversion would be 2027-28, not 2026-27.

“The agreement between the university and CUFA was that 2024-2025 would be year one of counting LTA positions toward a possible conversion to an ETA position, meaning that the eligibility for possible conversion would start three years later, in 2027-2028,” Fortier said in an email to The Link.

Several faculty interviewed for this article said they were not aware of the information presented by Fortier before being questioned on it by The Link, and were under the impression that the conversion would take place next year.

“It feels like the rug’s been pulled out from you. The idea that you may eventually have a more permanent position is just kind of taken away.” — Katherine McLeod, LTA professor

Taher-Kermani said he was shocked to hear the agreed timeline would be for 2027-28.

“I was not aware of it,” he said. “The anger, the outrage, came from the assumption that this is the year.”

“We are going by what the collective agreement states and counting from the start of the new collective agreement, which is 2023,” said limited-term English professor Katherine McLeod. “If the university is counting otherwise, CUFA members have not been informed as to why.”

Lack of clarity on the terms of the agreement extends even to some who closely followed the 2023 negotiations.

English professor Stephen Yeager, who was chair of his department from 2021 to 2024, said he was at a meeting with the negotiating team in 2023, before the collective agreement was ratified.

“Everyone I know who attended that meeting thought that the conversion to ETA positions would apply retroactively, to the years leading up to 2023,” Yeager said. “After the collective agreement was ratified, the provost's office told us [in 2024] the version you shared with me.”

A retroactive conversion, which was not promised under the agreement, would have allowed years already served under LTAs to count toward eligibility for extended-term status, granting some faculty job security even before 2026.

Yeager said he was “surprised” by Fortier’s wording of “eligibility for possible conversion,” as limited-term professors would technically be eligible if the university does create new extended-term positions.

“All LTAs are always ‘eligible for possible conversion,’” he said.

English graduate program director and professor Nathan Brown believes the university intends to save money not only by cancelling LTA contract renewals next year, but also by preventing the conversion of LTAs into ETAs.

“I think the reason the administration doesn't want that to happen is that, once LTAs become ETAs, then they enter into the step system of salary raises,” Brown said.

Fortier said that, while an LTA might have been converted to an ETA, “it does not mean that the individual who held the LTA would have been appointed to the ETA.”

“The collective agreement specifies that such conversions require a continuity of teaching needs,” Fortier said.

She added that, due to a reduction in course sections, the institution's teaching needs have “changed.”

“This is the year that many of us have been waiting for, and they're pulling the rug,” Taher-Kermani said.

McLeod echoed the language.

“It feels like the rug's been pulled out from you,” she said. “The idea that you may eventually have a more permanent position is just kind of taken away.”

Lesson learned the hard way

Perhaps “naive[té]” from the union is partially to blame for the fact that the rug can be pulled at all, said Brown, who believes CUFA made a mistake when negotiating the terms of the current conversion arrangement.

“[With] an agreement where LTAs are hired on one-year contracts year after year, and after the third year, they'll then be hired to an ETA―I think many of us are not surprised that the university then doesn't hire particular members back for that fourth year,” Brown said. “What I did not really anticipate is that they would cancel all LTA hires.”

CUFA’s communications and research officer Léa Roboam said in an email to The Link that the union is looking into the cancellations. She added that “current information suggests that not all LTA positions will be affected next year,” but declined to comment further on an “evolving matter.”

According to Fortier, 63 faculty members currently hold LTAs. Most have one-year contracts ending in June 2026, and a few have two-year contracts until 2027.

In her email, Fortier said that “all existing contracts will be honoured.”

A precarious position

The precarity of limited-term positions, said McLeod, long predates the decision to cancel them. She said the recent situation exposes the uncertainty and workload LTAs have dealt with for years.

Taher-Kermani recalled receiving his most recent contract two weeks later than in previous years, not knowing if it would come at all.

“I just remember those days being nightmarish,” he said. “I would wake up thinking, ‘Are they not going to hire us? Where is my contract?’”

The sleeplessness has returned these past weeks.

“I wake up at two in the morning with a sigh in my chest that made itself with grief; that, ‘Oh, is this how we're going to be treated?’” Taher-Kermani said.

While limited-term positions are theoretically meant to be short-term or sabbatical replacements, Sheftel said, in practice, many departments have had the same LTA position for over a decade.

McLeod said her LTA position in Canadian and Indigenous literatures has remained an LTA position for over 20 years. She has held six years of limited-term contracts in the position.

“It is really a permanent need,” McLeod said, “so I was quite confident that it would receive funding for next year.”

All work and no pay

Kaplow, currently Concordia’s only Latin professor, is on her eighth LTA contract for her position. She said that between her and the one other LTA in the classics department, they teach 42 per cent of the program’s courses in 2025-26.

“It would not be an exaggeration to say [Kaplow] is Latin at Concordia,” wrote classics student Rebecca Golding in an email to Concordia’s interim provost Effrosyni Diamantoudi and other faculty on Nov. 6, expressing concern that her professor may not be returning next year.

Kaplow currently teaches nine courses this year at the university, seven of them being Latin courses. She said she requested to teach two of them for free, as those classes are small and fall below the registration threshold.

“It is something I'm happy to do, because I do genuinely want my students to be able to [take these classes,]” Kaplow said.

“These positions were already cheap. It’s like if a hospital was going to try to save money by not stocking Band-Aids anymore.” — Stephen Yeager, professor

Golding said she and her classmates are “devastated” by the prospect that Kaplow’s contract won’t be renewed.

“These people do not deserve to be slapped in the face like this after all of the hard work that they've been doing,” she said.

During a two-hour university senate meeting on Nov. 7, Carr said he hopes to begin the hiring process again for faculty, including LTAs, in the future.

In interview, Taher-Kermani said that if he were rehired in the future, his ETA eligibility timeline would restart on a new clock.

“We would start afresh from [a new year] for another four years [before being] turned into ETAs,” Taher-Kermani said. “I think, if this is not exploitation, what is?”

Money talks

During the senate, Carr spoke at length about the necessity of mitigating “the most serious [financial] challenge in Concordia's recent history.”

He cited a steep decline in international student enrolment following tighter provincial and federal immigration and study-permit rules. Coupled with funding cuts from the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ), Carr referred to the situation as a “burning platform.”

The CAQ has imposed limits on foreign student enrolment, while Ottawa plans to reduce the number of Canadian study permits significantly, from roughly 306,000 to 155,000 by 2026.

Diamantoudi said in the meeting that replacing all LTA contracts with part-time contracts would generate $1 million in savings, an amount excluding recruitment and interview costs.

“If promises were made on limited-time contracts, that's a mistake, and also, they were not layoffs,” Diamantoudi said in the meeting. “Layoffs are coming, if we don't take prudent measures.”

Sheftel, in an interview, called the cancellations de facto layoffs, as did Golding.

“To cite the fact that their LTA contracts expire after one year, after having imposed said contracts on them in the first place, and after saying that LTAs would get promoted to ETAs after [three] years, simply does not make for a convincing argument,” Golding said.

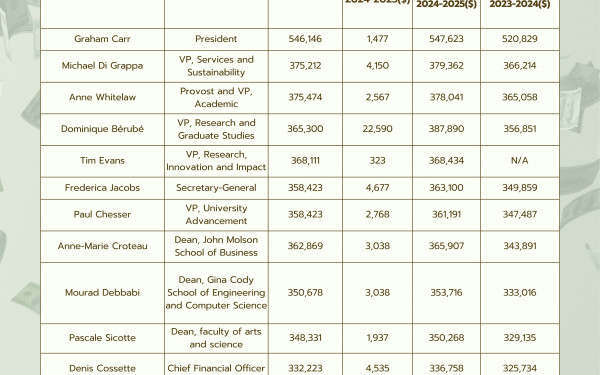

During the meeting, Carr, whose base salary exceeds $500,000, responded to a question about a “bloated ratio” of administrators to faculty and whether sacrifices would be made at the administrative level, saying senior administration has agreed to forego salary increases.

LTA salaries this year range from just over $78,000 to just over $90,000. Part-time instructors earn about $11,683, including vacation pay, per three-credit course. LTA salaries automatically include vacation pay.

LTAs teaching seven courses and earning around $78,000 are paid less than if they worked through the part-time union, which would net them almost $82,000 for seven courses.

“Though the part-time union won't even allow instructors to teach seven courses,” Yeager clarified.

Yeager, who held LTAs from 2009 to 2011, called the positions “exploitative and underpaid.”

“These positions were already cheap,” he said. “It’s like if a hospital was going to try to save money by not stocking Band-Aids anymore.”

No rest for the scholarly

The university has further said that, as part of additional cost-saving measures, it will introduce a voluntary retirement program for faculty and defer new approved sabbatical applications by one year.

Yeager, who has personally lost his sabbatical next year, calls this “disappointing.”

“If you don't get your sabbatical, then you can't do the research that will lead to your promotion,” he said, “but all of that matters much less to me than our colleagues losing their jobs.”

Despite “intense” uncertainty, many LTAs expressed that they seriously care about the university and their students.

“I've never worked in a place where I felt so self-belonged, both with my colleagues and with my students,” Taher-Kermani said.

Brown and a number of his colleagues say the faculty want the administration to consult them over how the deficit should be addressed.

“We are going to carry this with us, and our colleagues who remain will hold on to this unfolding of mistrust,” Taher-Kermani said. “Removing us from these jobs and these contracts may terminate us at Concordia, but it will not end us as living bodies and individuals, as academics, as intellectuals.”

The limited-term professor warned that the impact of the administration’s decision will be immense and irreparable.

“They may be able to remove us, but this is not going to go away, and this will never be forgotten,” Taher-Kermani said. “The ending of our story should be crystal clear to our students.”

A previous version of this article stated that Lauren Kaplow teaches nine Latin courses at the university. In fact, of the nine courses Kaplow teaches at Concordia, only seven of them are Latin courses. The Link regrets this error.