The PHI Centre welcomes art enthusiasts with open arms after months of closure

‘Parallel Lines,’ PHI’s latest exhibit, showcases 10 projects by local artists that depict life in the pandemic.

Montreal’s PHI Centre curated its grand reopening for the public on Feb. 24 for the very first time since October.

The multipurpose space located in the Old Port warmly welcomes its visitors to its very first virtual residency: Parallel Lines. This new installment allows visitors to explore 10 creations by local artists—creations that embody different ways that the pandemic has impacted artists in Montreal.

PHI’s virtual residency began last April, just after the pandemic struck Montreal. The venue reached out to the city’s art community to reflect on how they were coping at home following government protocols to maintain safety regulations.

Applications came flocking in, full of innovative ideas that reflected each candidate's experience of isolation. The proposals included various sensory art forms that depicted the artists’ visual, auditory and written experiences of life at home in the pandemic.

Of 192 applicants, 10 lucky artists’ proposals made the cut. Winners also received a 2,000 dollar grant award. Thus came the birth of innovative ideas that would allow artists to showcase their work from the comfort of their homes.

When the callout ended on April 1, PHI immediately launched into its 60-day time frame to bring the winners’ various creations to life.

The culmination of all 10 art pieces shares one single commonality: that everyone has their own definition of “isolation.”

Catherine D’Amours and her partner, Nicholas S. Roy, are a duo from the batch of artists whose works are currently on display at the PHI Centre. For them, the goal was to comment on how most Montrealers are feeling in a pandemic-stricken world through their visual sensory project, Ça va/It’s OK by Gauche/Droite.

Gauche/Droite refers to many qualities of the human experience. According to the couple, their work can be interpreted as the notions of “left” and “right” on the ideological spectrum, or as the functionality of the human brain’s left and right hemispheres.

In essence, the duo wanted to explore the notion of duality, and how our minds register or distinguish “the left” from “the right.” Their project categorizes how people in quarantine have been spending time on social media.

“We were all confined, and we wanted to find a way to specifically say something about the situation but to also bring a little joy in this pretty dark episode,” said Roy. “The goal was to reach as many people as possible just to make them smile.”

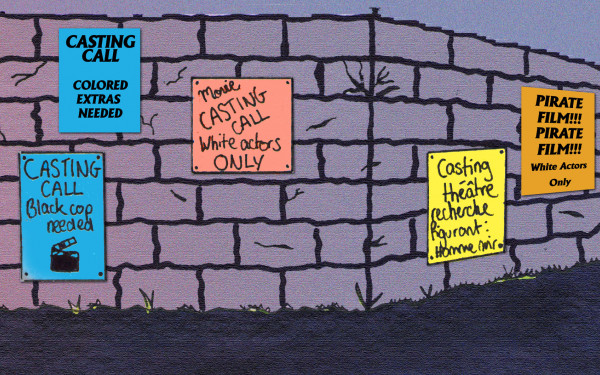

The duo’s piece is a form of commentary on how people stuck at home are spending most of their time in front of their browsers. They wanted to create a physical space that represents the kind of online activity people at home are conducting on the internet nowadays.

According to the duo, people spend most of their time online doing work from home, searching for entertainment and news, or for retail purposes.

For D’Amours and Roy, most corners of our daily lives seemed to have begun revolving online since the start of the pandemic. Together, they define their work as “street art performance for websites.”

“The idea was to comment [...] on these different news sites, or food blogs, or shopping sites, and make them live through art,” Roy added. “Although there is always the question of whether it is art for art’s sake, I know that when I create something, I want to see how it resonates with people.”

“We were all confined, and we wanted to find a way to specifically say something about the situation but to also bring a little joy in this pretty dark episode.” — Nicholas S. Roy

Souvenirs to Nowhere, by multidisciplinary artist Naghmeh Sharifi, is also being showcased at the PHI Centre. Her piece includes 22 paintings on wooden panels that depict fragments of the artist’s daily life with the help of solvents and Prussian blue paint.

“I was inspired by notions of nostalgia that are transforming or changing,” said Sharifi.

Nostalgia is usually a representation of the past but the past seems to be intermixing into the present for this artist.

“[When the confinement first began last March], people were becoming nostalgic over life just the week before, or life two weeks before,” she added. “That was very inspiring to me; moments of isolation, confinement, anxiety, self-care.

Sharifi began recording all of these elements that saw her through those early stages of the pandemic. In doing so, she was successfully able to turn her experience—and nostalgia—into her very own masterpiece.

“I began recording optics and elements that are mainly considered banal and mundane,” she added. In her paintings, the artist often refers to the everyday objects surrounding her apartment, such as the maintenance of plant life, an ashtray with cigarette buds, and her housecat. “They were the things really seeing me through this time.”

The point of this virtual residency was to make content out of the spaces that artists were confined to, those being their homes in Montreal.

Typically, a residency program allows artists to use a certain amount of time and space to develop preconceived or inspired content. This content is usually defined by the context and geography provided to the artists by the curators. For this particular project, the artists had a 60-day time frame to produce works inspired by the confinement of their living spaces at home.

Artists like Sharifi were thus forced to draw inspiration from the elements surrounding their everyday lives.

In her artwork, Sharifi attempts to replicate the social media grid format we often see online with the style of polaroid pictures to create a makeshift melancholic album of souvenirs⎼ Souvenirs to Nowhere.

“Looking at social media, I noticed that a lot of people remain inactive unless they want to record an image or instance when they are travelling somewhere,” she added. “People rate an experience worth capturing when it is exotic, and I wanted to shift that around.”

The combination of capturing the human form and its psychological traits are exemplified in Sharifi’s work, like that of many other artists whose craft is on display at the PHI Centre. The work of Dayna McLeod is no exception to the ongoing theme.

McLeod is a queer Montreal-based artist who specializes in videography and performance art. Her piece, appropriately titled Restless, is a collection of surveillance footage of the artist and her partner fast asleep over the period of the 60-day residency.

McLeod’s history of sleep disturbances is meant to give viewers an inside look at the agitation and restlessness that can be associated with life in confinement and isolation, as well as in those who struggle with sleep problems.

“People can see how the behavioural patterns seen in sleep-deprived individuals like myself share similarities to our current desperation for life to go back to normal again,” she said.

Through this project, McLeod’s experience in confinement allowed her to take a deep interest in the way surveillance and invasion of privacy, in general, became a big focus for people stuck at home. She believes that life online has left us more exposed than ever before.

“I placed my camera by our bedside to imitate the feeling of voyeurism among viewers, except there is nothing overtly sexual about it whatsoever, other than the fact that we are sleeping by each other,” she said. “There is a psychological element in there that I think needs more digging.”

Whether the 10 artists struggled with living in isolation during the pandemic or not, Parallel Lines is meant to leave visitors questioning how these various narratives of life in confinement are interchangeable.

The beauty of this exhibit is found in its allowance for visitors to explore the idea of being ““alone together” through this experiential scenography.” Parallel Lines is accessible both in person until June 15, as well as online as a virtual tour on the PHI’s website.