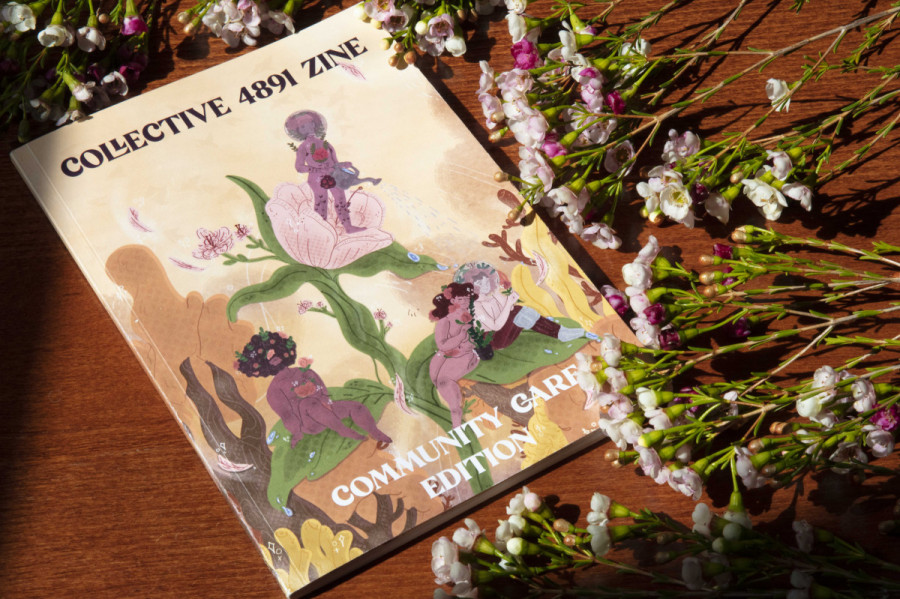

The tender roots of Collective 4891’s zine: Community Care Edition

The non-profit passion project founded by two Concordians is sustained by emerging artists

When I met Shin Ling Low and Hannah Jamet-Lange, they were double-masked and highly observant of the social distancing guidelines at Westmount Park. Under reawakening trees, the two co-founders of Collective 4891 hesitated to sit any closer than on opposite ends of the bench.

The pair behind the artist collective revealed it was the first time they had seen each other in over six months. The two smiled proudly for the camera while holding the first copies of their zine in hand: Collective 4891 Zine: Community Care Edition. Launched nearly a year after the pandemic halted in-person open mic events, the zine was born as a physical manifestation of a safe space for emerging artists.

The theme of community care is split into three chapters in the zine: “Revolution,” “Reflection” and “Rebuilding.” Each section features quotes from thought leaders honouring what the collective defined as crucial stages to community care. Featuring poetry, creative essays, photography, painting, and other visual arts, the zine embodies a graceful yet resolute declaration of anti-oppression and liberation.

“Some of the pieces really moved me. It was really intimate, like we were entering their world and we had to be respectful of that,” Léa Lagier, an editor at the zine said.

Low and Jamet-Lange told me the story of their passion project on the soccer field’s bleachers, their softness reflected in the tender breeze on a Montreal spring day. It began when Low and Jamet-Lange met in Concordia’s communication studies program.

“During our first year, we were constantly surrounded by people who did really cool projects and made art. But we found that in the academic context, it was often hard to really see everyone’s work well. We really wanted to create a space where people could present their art and their work in a non-academic context,” Jamet-Lange said.

The project began with small events hosted in Jamet-Lange’s living room, where artists shared spoken word poetry, music, and digital art. They named it the Collective 4891, after the apartment’s street number that hosted the first events.

“We were really just trying to create a comfortable space where people felt safe,” Jamet-Lange said. The collective’s first event in April 2019 had 35 attendees, most of which were Concordia students. Through word of mouth, events quickly grew to 60 attendees at their peak, averaging between 25-45 for most events.

Low and Jamet-Lange believe that it was the safe environment for emerging artists that attracted new faces as well as returning ones. After each performance, feedback sessions were held.

“A lot of the time it wasn’t even criticism, people were just really excited to share how much they loved the work,” Low said. “It was a really beautiful, personal, and intimate space. It really blurred the lines between performer and audience.”

Events were also photographed and filmed, with footage sent to each performing artist to serve as resources for professional projects outside of the university.

For the most part, Low and Jamet-Lange organized events independently without any funding. Their initial events had a mic that was borrowed from a friend, and a speaker from an ex-roommate. Attendees would sometimes donate money, paying for snacks and beverages each time.

The collective began to attract attention from the Concordia Student Union, which co-sponsored an event that was held at The Hive Café’s downtown location in September 2019. With around 80 attendees, the event featured a theme of climate activism.

“It was a really beautiful, personal and intimate space. It really blurred the lines between performer and audience.” — Shin Ling Low

The collective’s last in-person event was scheduled on March 15, 2020, and was cancelled due to COVID-19 lockdown measures. To continue serving as space for artists to share their work, Low and Jamet-Lange moved their events online, holding an Instagram Live at one point, and a Google Hangout at another. The idea of a zine floated last summer, during a lull at the collective.

“We threw out the idea earlier on in the pandemic, when [the] Black Lives Matter movement started becoming more mainstream,” Low said. “Around June or July, we decided to actually make it happen, and we started to apply for funding.”

Low and Jamet-Lange secured funding from the CSU, Quebec Public Interest Research Group at Concordia, and the Fine Arts Student Alliance at Concordia. By September, the collective was able to put out a call for editors and graphic designers, followed by a call for submissions.

“Both of us strongly believe in paying people for their work. And for the artists, if we were going to publish this, we wanted the artists to get honorariums,” Jamet-Lange said. “We don’t want to place a monetary value on any kind of work, but at the same time, we live in a capitalist society where we do need to pay bills. Because of that, it’s important whenever possible to pay artists for their work. Both to provide a space to publish their work and not exploit them for that.” All of the seven editorial staff were paid for their work on the zine, and all 21 artists were paid for submissions.

Inspired by the theme of community care, Low and Jamet-Lange decided to distribute copies of the zine through donation-based fundraising. In an effort not to make a profit from a funded project, the collective is asking for supporters to send receipts of donations made to local non-profit organizations of their choice that support an overall goal of anti-oppression. When a receipt is sent, the collective mails out a copy of the zine.

“It was really nice that this was donation-driven and non-profit,” said Anayis Ecityan, a graphic designer for the zine. “Everybody could choose where to send their support, which was really so cool.” The collective’s fundraising goal of $800 was reached in less than two weeks.

For the editorial staff, the zine served as a memorable experience, from which they look back at fondly and hope to set as a standard for future professional endeavours.

“It’s been a grounding experience,” Ecityan said. “It’s been a really lovely experience getting to know all these people and working on such a fulfilling project.”

Low and Jamet-Lange are in the process of deciding the future of the collective, but they already have plans for another zine. While the future is still uncertain, it is clear that the project’s impact is everlasting among the team.

“I hope that even after we’re all graduated, that the Collective can continue and other students will take the lead,” said Aaliyah Crawford, another editor for the zine. “That this grows into something that is ever-present and continues offering opportunities to other students in knowing that if they have something they’re passionate about, there’s ways to make that happen.”

web_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)