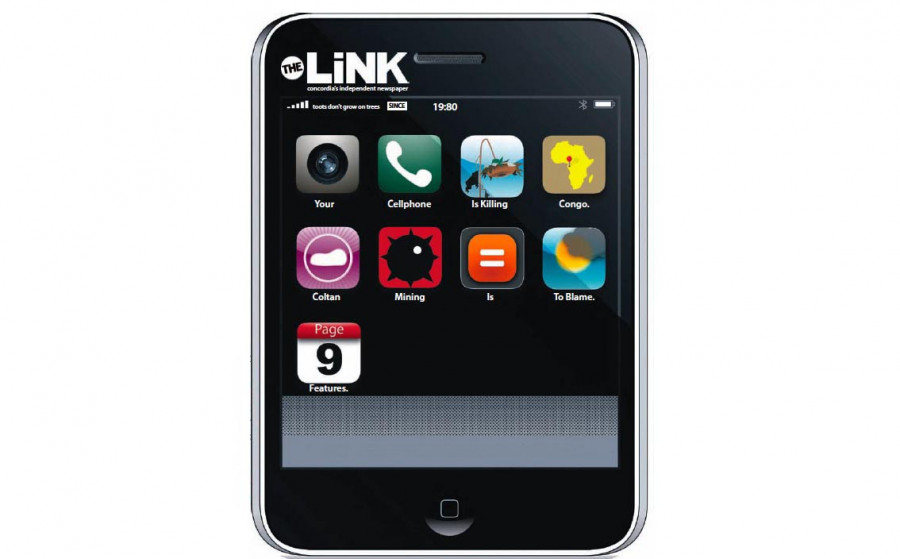

The Coltan Conundrum

How a Mineral Essential to the Cellphone Industry Contributes to an Ongoing Human Rights Nightmare

The smartphone industry is booming and there is no sign of it slowing down. The mobile phone market is expected to be worth over $200 billion USD in 2013.

But with the growing demand for smartphones, there is also a growing demand for the precious ore coltan—approximately 80 per cent of which is mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Coltan mining in the Congo may be the most overlooked problem that is literally in our hands.

After extraction, coltan ore is refined into tantalum, a highly conductive metal that is a necessity in producing smartphones—it’s found in every type, size, model and brand. It’s inside laptops, mp3 players, Xbox controllers and much more. Coltan is in such high demand that the industry surround the mineral brings in about $2 billion a year worldwide.

Usually, when a state becomes resource rich, the citizens tend to prosper, but the Congolese have not basked in the benefits of a resource boom. On average, its people earn $710 a year, which ranks it as one of the poorest countries in the world—201 out of 208 according to the World Fact Book. To compare, Canada’s per capita income is $29,740.

Congolese miners work in deplorable conditions. Researcher Charles Chalondakwa of the Institut Superieur de Développement Rural Bukavu said in a Pulitzer Center documentary, Congo’s Bloody Coltan, that “they dig naked.

They are unprotected. They use a simple flashlight you buy at the market with two batteries. Their hands are bare while using a chisel and a hammer. Some die in [the mines]. There is no air down there. These are unimaginable conditions.”

Local human rights organizations say that it’s not uncommon for police officers or government officials to extort miners for their daily earnings, and millions of people have lost their lives to a war enabled by the mining industry.

The situation is dire, but who is to blame? On one hand, demand is fueled by consumer behaviour, but international companies are the ones who own the means of gathering resources necessary to make a given product. Is it the consumer’s fault for not demanding a product go through proper fair-trade agreements, or is it the responsibility of international companies to gather coltan legitimately, regardless of consumer demand?

Reality of the Game

Dr. Samantha Nutt, founder and executive director of War Child told the The Globe and Mail that resolving the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo will “require a tremendous amount of initiative that is going to have to ultimately come from consumer momentum and from the industry itself.”

A smartphone costs anywhere from $150 to much more—an Apple 32 Gb iPhone costs over $300. The cost of these phones would be even more expensive if coltan was mined with ethical labour practices. Would consumers pay substantially

more for an iPhone if they knew it would improve the situation of the Congolese? They should, but they don’t have to—that’s their choice.

Concordia Marketing Professor and author of The Consuming Instinct, Dr. Gad Saad believes that one must recognize the biological forces that have compelled consumers to engage in the behaviours that they do. According to Saad, the problem comes from what he calls the “Tragedy of the Commons.”

He said that it is easy for someone to say they are in support of saving those suffering as a result of coltan mining in the Congo, but that person may think their actions are a small drop in a larger bucket so they don’t have incentive to act.

“The intoxicating pull is that everyone thinks this way,” said Dr. Saad, also a Psychology Today blogger.

But it’s not about whether or not consumers would be interested in purchasing a zero-conflict smartphone, because they are. The average consumer wants a product that will make them feel good about the choice they make. But Dr.

Saad believes that in order for consumers to make conscious choices towards alleviating the conflict, consumers have to “find a way to make the Congo fit within their concentric circle of influence.”

“It is very difficult to keep intimate relationships with more than 150 people,” said Saad, reflecting on the Dunbar theory, which hypothesizes that there is a limit on the amount of people with which one can maintain a social relationship. “So asking for someone from Montreal to feel an affective reaction to something in Congo without any local base, it is equivalent to asking them to care about something happening on Jupiter.”

According to Saad, the key is to make global issues into local ones.

“You have to make coltan mining part of a consumer’s daily reality rather than a global issue. You have to convince the consumer that they can have an impact on it and it is relevant at a local level,” said Saad. “If it isn’t then it’s simply counting on people to be altruistic in a general way.”

Saad isn’t suggesting that generosity doesn’t exist, but that it is easier to convince people to care if it impacts them directly.

“Take for example helping a needy African child. ‘Please give money to African needy children’ doesn’t work. But ‘Give money to your foster child named [insert name here]’ works a lot better, even though in both cases you are still asking for money,” said Saad.

Positive Measures

In the recent past, there have been failed attempts to boycott cellphones manufactured with embezzled Congo coltan, such as the “No Blood on my Cellphone” campaign in Europe. Unfortunately, the campaign proved futile in slowing down the demand for cellphones produced with blood coltan.

Canadian human rights organizations have also been fighting for justice in the Congo. A Montreal-based mining company, Anvil Mining, has been accused of fueling the Congolese civil war and on Nov. 9, 2010, the Canadian Coalition Against Impunity filed a class action lawsuit against the company. The Gazette quoted them saying the mining company provided “logistical assistance, played a role in human rights abuses, including the massacre by the Congolese military of more than 70 people […] in 2004.”

But six days later, the mining company logged a record of $6.1 million net earnings in the third financial quarter, compared to last year’s net loss of $0.2 million during the same quarter. Despite accusations of being an unethical company enabling the Congolese civil war, their stock price did not suffer. In fact, the company’s stock index closed at $5.02 on Nov. 9 and peaked at $5.81 on Dec. 1.

In the stock market, social responsibility plays a secondary role to the bottom line.

“Governments should pass legislation to regulate [mining in the Congo] and companies should track where they get their minerals from to ensure it’s not financing conflicts,” said Dewar in a recent The Globe and Mail live chat.

Efforts have been made by New Democratic Party MP Paul Dewar to combat this issue. He tabled a bill—Bill C-571, the Trade in Conflict Materials Act—with support from the Liberal Party of Canada. If the bill is turned into law, Canadian companies would be held accountable for the means through which they gather resources, and in turn, stop funds from keeping the war in Congo alive.

But the responsibility to change Congo’s fate doesn’t only lie on the government and those directly involved in the mining industry. Consumers and citizens can play a direct role in the lives of millions of Congolese people by petitioning for their institutions to pressure technology companies to regulate the mineral, supporting Bill C-571, being aware and spreading the word on where their smartphone comes from, and making this a local issue.

“I believe there’s widespread support, not only in Canada, but globally, to regulate conflict minerals,” said Dewar. “That’s where citizens come in. Voices should make the difference.” Therein lies the irony of coltan mining—in an industry that relies on voices for survival, those same voices can also affect the biggest change.

This article originally appeared in Volume 31, Issue 18, published January 11, 2011.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

2_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

__600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)