Street Artist Roadsworth Takes His Art Indoors

If one ventures out to see Roadsworth’s exhibition Off and On at Galerie Punkt, a larger-than-life banana peel will greet you.

The spray painted peel is a visual pun. It sits innocuously in the centre of the street, waiting for someone or something to come and slip on it.

Roadsworth has taken this Warhol pop art icon and peeled it. He takes an icon drained of meaning over time and over-usage and re-contextualizes it. This piece reinvigorates and reactivates the dead space of the street.

This is Roadsworth—an artist that transforms public space and, through his art, exerts his freedom to express himself. His works urge the public to rethink what we may naively dismiss as vandalism when, in fact, it is art.

Peter Gibson is the man behind Roadsworth. Gibson took to the streets in late 2001 when he began spray-painting bicycle lanes on roads in the early mornings. This gesture was an artful protest about the lack of bike lanes in the city.

He is now world-renowned for his public act. Playing with lines, corners, city lamp shadows, parking lots, walls and plain ol’ cement, Gibson transforms public space from a drab system of boundaries and rules to a space for people to ponder the meanings and intentions of his work.

He paints a giant ecological footprint on the street.

“If you’re from Bangladesh, your ‘eco-footprint’ is about the size of…a foot,” he says. If you’re from North America it takes up the space of one sidewalk to the next.

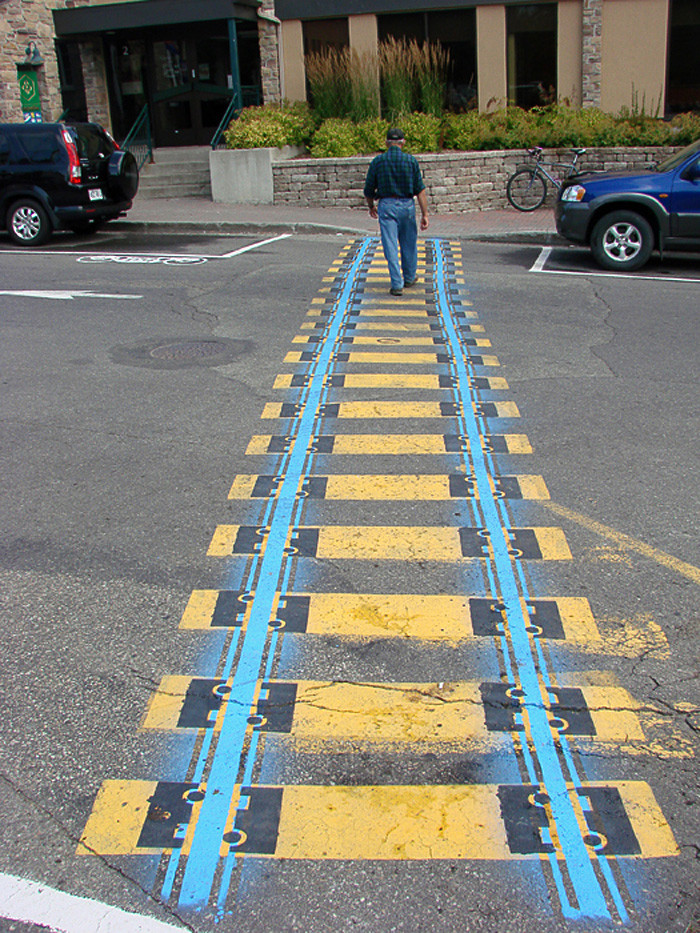

He inserts one-dimensional runway lights along roadsides to simulate the feel of a fashion runway. His intention is to mock the inflated notion of glamour that is used by the car industry to sell cars. He sprays windows and doors on the sides of garbage cans and calls it “Affordable Housing.”

He also gets fun with his art. In one instance he covered a street in birthday candles. He turned a photograph of the piece into a birthday card for his father and on the inside wrote “Happy Birthday Dad! Your son is a vandal!” He transforms street markings into zippers, plug-in outlets, heart-rate monitors, lie detector tests, film reels. He plays with parking lot markings, churning ordinary lines into a cement field of bursting dandelions. Roadsworth also makes use of shadow: stenciled children tightrope walk a shadow while lions are painted onto the projected shadow of barred windows, mimicking the idea of caged, wild animals.

Roadsworth doesn’t save his art for galleries; he thinks outside that box and puts his art in people’s faces. But now, for the first time ever, Roadsworth’s work can be found inside a gallery space.

“In the gallery I have less to react against. It takes more to make a statement. There are less visual cues [and] less physical attributes to play off of,” said Gibson.

“There’s a lot of politics in public space; it makes an automatic impact,” added Gibson.

Off & On is being displayed at Galerie Punkt, an incredibly small space that caters to big thinkers.

Melinda Pap, the gallery’s owner, didn’t mince words when she explained her vision of the gallery as a multidisciplinary venue that welcomes all forms of expression. A gallery, she said, is not limited to one field or category.

“Creation—you cannot separate. How can you make a painting if you do not know how to draw? How can you make an installation if you do not understand space? How can you build a house if you do not know how to build the foundation? The house will fall apart.”

In this way, Pap makes the point that artists today are limited by a one-dimensional educational system and categories that fulfill the requirements of government grants.

But what about creativity? To be a good artist you must be open-minded and seek to understand everything. You must have a “global vision,” as Pap put it.

“Creation is the freest thing on Earth. How lucky we are to have a métier like this? You don’t depend on anybody, just on one’s own knowledge and passion.”

On one wall of the gallery, Gibson exhibits some of the epic stencils he has used over the past ten years. On the opposite wall he offers a full-blown hyper-intense scene of images that re-occur in his work.

“I was a musician before I was an artist and the idea of the show was a mural. I was working like a music producer works with samples, only they were stencils intended for mostly outdoor public art, out of which I created this story or narrative, using these samples.”In one scene, human-sized silhouettes of folk-tale children sit on tree stumps. They gaze upon a projection of scenes from The Empire Strikes Back and, in an alternate scene, skip across into scenes of pastoral utopia.

Images of cow skulls, sunflowers, vultures, canoes and waterfalls fill the wall space. An iconic boy fishing has caught a giant fish that struggles violently against the barb it’s hooked on. On the floor of the gallery, an idyllic scene of a Japanese-print catfish swirls inexorably towards a massive drain at the other end of the floor.

In another scene, a Death Star looms behind a TIE Fighter mask whose lasers become a highway. The highway divider becomes a cord that is unplugged from its socket and wraps around a landscape of tree stumps.

The plug-in the cord searches for, through natural images of safety and cryptic images of fear, sits just inside the door to Galerie Punkt, beckoning us to rectify the situation.

You can catch Off & On at Galerie Punkt (5333 Casgrain Ave.) until Nov. 21. Admission is free.

This article originally appeared in Volume 31, Issue 13, published November 9, 2010.