Divestment’s On You

Divestment Conference Aims to “Build a Stronger National Movement”

Divestment from fossil fuel ventures is not symbolic, educator Crystal Lameman says.

She cited a quote from Canadian environmental website Alternatives Journal: “It’s often suggested that divestment is an important symbolic gesture. But at this point climate change is an emergency—one that demands more than just gestures.”

Lameman—of the Alberta Beaver Lake Cree Nation, where a large portion of land was leased for tar sands exploration—was one of four keynote speakers in H-110 to kick off the first conference on fossil fuel divestment in Canada, called Fossil Free Canada Convergence, which brought hundreds of students from across the country together last weekend to network and strengthen their university divestment campaigns.

She said the journal’s statement made her scratch her head.

“It’s not a symbolic gesture because as universities realize that the very economy that is perpetuating climate change and further assisting in the destruction of the place my children call home, they’re also getting to understand that […] we will always be able to go to the land to sustain ourselves,” she said. That land is being threatened and “over-industrialized” by energy companies, she added.

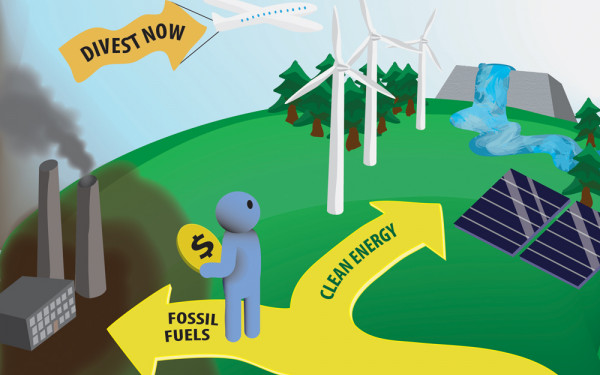

Divestment is the first step in pulling the economy away from “dirty” energy investments, co-founder of Aboriginal Youth with Initiative Clayton Thomas-Muller told The Link.

“If we can get university endowments out of fossil fuel investments, then maybe we can get the Canadian Pension Plan out of dirty fossil fuel investments, maybe we can get faith-based organizations out of dirty fossil fuel investments,” he said. “Change always comes from young people.”

One of the conference’s organizers, Kelsey Mech of the Canadian Youth Climate Coalition, says one of the event’s goals is to “build a stronger national divestment movement.”

Each of the four speakers—Lameman, Heather Milton-Lightening, Denise Jourdain and Alyssa Symons-Bélanger—detailed in French or English their different experiences with activism and how fossil fuel exploitation had affected their lives and the lives of those around them.

Milton-Lightening’s speech revolved around the theme of youth’s power to effect change. She told a story of how she fled her adoptive home at 16 to Winnipeg, where she attended Children of the Earth High School and became an activist. She and a group of teenagers walked across the country in the name of Indigenous rights.

“I want to remind you that there is a responsibility [for] young people […] to experience new things, to learn as much as we possibly can, but also to go out there and be active, to take action, to stand up and speak out,” Milton-Lightening, who was also a part of the Indigenous Tar Sands Campaign, said.

She referenced systemic issues that stem from an economy dependant on large corporations.

“Transnational companies have more power than the countries and we’ve given it to them. How do we fundamentally challenge that?”

A Canadian University Ahead On the Trail to Divestment?

Canada has a ways to go before catching up with the 13 American universities that have pulled out of their fossil fuel investments, but several Canadian universities are heading in the right direction, said Mech.

She pointed to a small number of universities that have struck investment committees to consider divesting, “and it’s looking pretty positive that one of those may be reaching a positive decision in the next couple of months.”

Dalhousie student and member of Divest Dalhousie Scott Thomas walked by as Mech was speaking with The Link.

The university’s board of governors is meeting Nov. 25 and “that’s when we’re calling for their decision to be made [on divestment],” he said, explaining that the students’ campaign was a year-and-a-half old.

The Importance of Networking

Symons-Bélanger spoke of the importance of networking with activists across the country to join forces and better organize themselves. She referenced a recent blockade against the proposed pipeline at Montreal’s Enbridge refinery east of the city, where she and another activist locked themselves to a fence to protest the proposed the company’s 9B pipeline. She attributed the protest’s success to the support of activists she had met throughout the province.

“We couldn’t have performed that action if we didn’t have the Marche des Peuples pour la Terre Mère and the profound links we’ve made with other activists,” Symons-Bélanger said.

Jourdain, the first to speak, talked about the injustices brought onto her community by the provincial government’s plans to exploit energy resources in northern Quebec. She said the residents of Sept-Îles, the municipality a block away from her Innu community Uashat mak Mani-Utenam, had received more detailed explanations of the Plan Nord than the Innu village.

Bridging The Language Gap

Concordia and McGill may have been the first to step up when the conference was pitched to universities across the province, “but we’re so glad it’s taking place here,” Mech said.

“We think there’s definitely a missed opportunity in Canada—in organizing right now—to connect anglophone and francophone organizers.

“There is so much amazing stuff going on in both of those organizing worlds and they’re so often not shared with one another and not held up and amplified and elevated,” Mech added.

For that reason, the conference’s workshops were held in both languages and headphones with simultaneous translation were available for audience members at the keynote speeches.

1_591_1050_90.jpg)

2_675_1200_90.jpg)

3_591_1050_90.jpg)

4_590_1050_90.jpg)

_600_832_s.png)