Building anarchism, one page at a time

Montreal’s Anarchist Bookfair celebrates its 11th edition

Glass shards lay scattered on the ground in front of a large chain store on Ste-Catherine Street West. A young punk, his face covered with a black bandana, screams at a line of riot police. Molotov cocktails and rocks fly through the air.

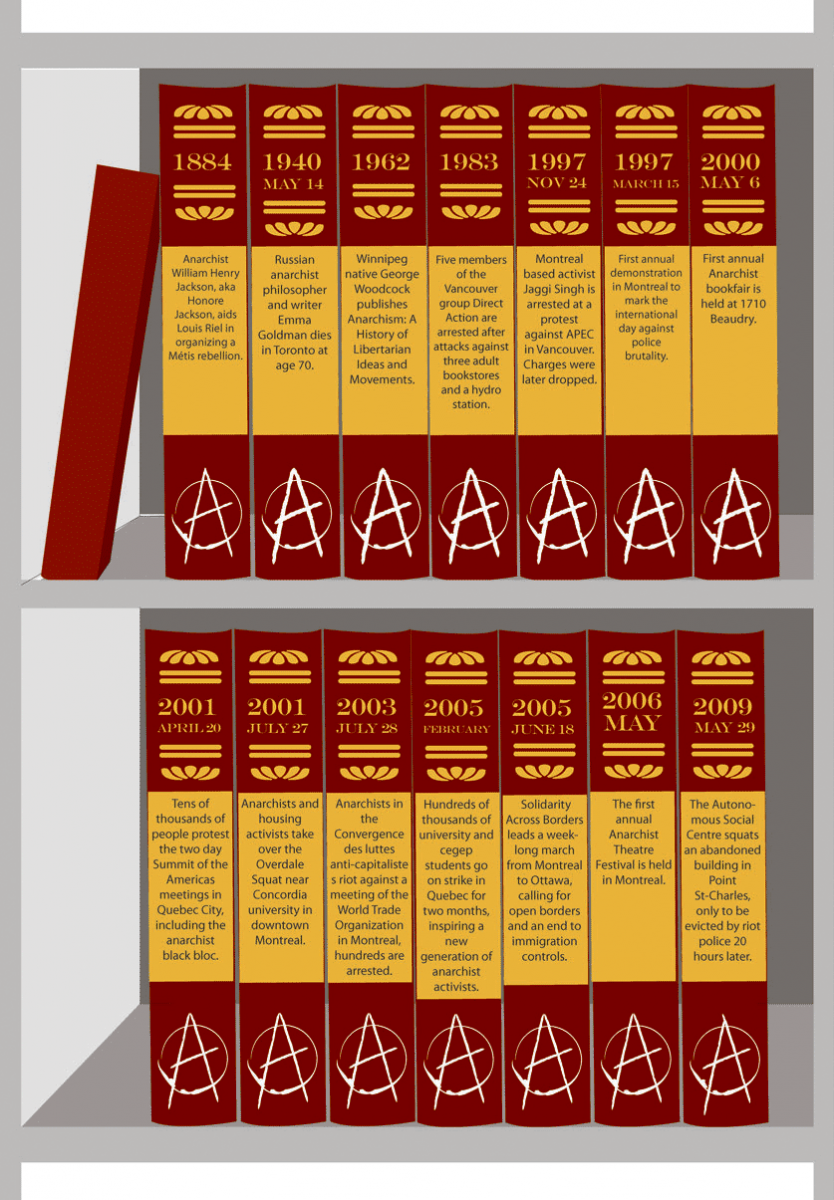

Though these are the typical images associated with anarchism in Montreal, there’s a much broader picture to the political ideology that stems back over a century in this city.

Anarchism, the belief that formal government is unnecessary and therefore illegitimate, has deep roots in Montreal’s communities, from factories to academic institutions like Concordia.

“No gods, No masters, No bosses, No borders” is a typical anarchist cry which encompasses the “freedom-loving” ideology. But while anarchists have a reputation for standing on a soapbox, they can be found to effect change through action.

“There are a lot of myths around anarchism,” explained Sebastien Thibeault, a member of anarchist federation l’Union communiste libertaire. “One of the more persistent myths is that anarchism is only a subculture.

The reality is that anarchism has been rooted in working-class struggles ever since the emergence of modern capitalism.”

Testament to the growing anarchist culture in Montreal, thousands of people converge in a modest community centre in the South West neighbourhood of Little Burgundy every May for the Montreal Anarchist Bookfair. It is a colourful gathering of hard-line anarchists, zine-makers, student activists, community organizations and many who are just curious about anarchism and what it stands for.

This year marks the 11th running of the book fair, which will take place over two days from May 29 to 30.

“That the anarchist book fair has not only lasted for 10 years, but grown tremendously, is a testament to the need to carve out our own niches and a testament to the commitment of anarchists and non-anarchists who have critiques of the current global system [and want] to look for better [alternatives],” said Amanda Dorter, a member of the book fair’s organizing collective.

More than simply a space for independent anarchist publishers to sell their books and magazines, the book fair is a multi-day festival that includes workshops, activities for kids, art exhibitions and concerts. In past years, organizers estimated it has drawn over 5,000 people and tout it as the largest anarchist event in North America.

Publish or perish

“The first traces of anarchism in Quebec go back to the 19th century,” explained Mathieu Houle-Courcelles, author of Sur les traces de l’anarchisme au Québec. “More concretely, there was an anarchist movement which took form at the beginning of the 20th century, notably after 1906 in Montreal. For the most part, it was coming from new immigrants from eastern Europe, mostly Jews, who formed very dynamic anarchist organizations which held a dominant place on [Montreal’s] political landscape until the First World War.”

According to Houle-Courcelle’s book, these immigrant anarchists set up bookstores and publishing offices downtown, mostly around the corner of St-Laurent Boulevard and Ste-Catherine Street, in what has become the gritty Lower Main district.

These would-be revolutionaries were poor workers who rallied behind the the creation of labour unions, particularly for factory workers in Montreal’s women’s garment district.

Despite Montreal’s vibrant history of anarchism, one would be hard pressed to find many long-standing anarchist organizations, or many anarchist activists over the age of 30.

In the movement today, a common term is “activist burnout,” a tipping point that traditionally comes after years of criminal charges, long meetings, too many beatings from the police or simply the stress of being involved in day-to-day solidarity work.

Thibeault suggested that the longevity of the Montreal Anarchist Bookfair is a sign that the stereotypical flash-in-the-pan style of anarchism is fading.

“Years ago, there was little to no chance of getting past the five-year mark for an anarchist organization in Quebec. Now it is a reality for many collectives,” he said. “The Summit of the Americas [in Quebec City] in 2001 and the large student strikes of 1996, 2005 and 2007 were largely responsible for the realization that durable, long-lasting anarchist organizations are a necessity.”

“In Montreal, you’ll have organizations fighting against the state of affairs, but at the same time trying to set up alternative ways of being,” said Anna Kruzynski, an anarchist activist and a professor at Concordia’s School of Community and Public Affairs. “Often this is not portrayed in the media because it’s [a coalition within] an everyday neighbourhood or [the result of] community-based organizing; things that are not visible to the general public.”

Kruzynski was involved in a large anarchist initiative called the Autonomous Social Centre, which tried to squat in an abandoned building in Pointe-St-Charles last May. The goal of the squat-in was to petition for the building of a multi-use community centre in the neighbourhood.

Rooted within the walls of Concordia University, part of Kruzynski’s research on anarchism includes work she does with the Collective for Research on Collective Autonomy, a group which conducts research on anti-authoritarian, pro-feminist movements across Quebec.

“It’s important that many of these initiatives that are not available to the public eye be documented,” said Kruzynski. “This kind of research allows us to debunk some of the myths about anarchist activism.”

Houle-Courcelles agreed that anarchist publishing has greatly contributed to this demystification of the movement.

Through an increased access to publishing and no shortage of websites and blogs on the subject, anarchists have been able to put their ideas out to the world and get around the stereotype that anarchism only stands for chaos and violence.

“Over the last 15 years, the many books which have been written about anarchism in Quebec have fleshed out the ideology a bit, and has allowed people to see that anarchism doesn’t limit itself to the existing prejudices against it,” said Houle-Courcelles.

All that’s left

Anarchists aren’t the only ones on the radical left who are engaged in publishing and book distribution in Montreal. Last March, the Revolutionary Communist Party, a Marxist-Leninist-Maoist group, opened up a bookstore called the Maison Norman Bethune near Frontenac Metro.

While their bookshop stands in contrast to the anarchist bookshop l’Insoumise on St-Laurent Boulevard, RCP member Jacques Beaudoin insists that the Maison Norman Bethune isn’t trying to compete with anarchist publishing.

“We value the distribution of any book, including books that aren’t of the same political orientation as ours, but that the text allows us to better understand a given social issue,” said Beaudoin. “The more leftist bookshops, the better.”

Meanwhile, organizers of the Montreal Anarchist Bookfair are already gearing up for the 2010 edition of their event.

While the thought of a building full of punks and counter-culture radicals might be off-putting to some, Dorter encourages everyone to come out to this year’s book fair whether anarchist or otherwise.

“There really is something for everyone here. We live in a place where cops racially profile and kill people with impunity, where migrants are being deported at increasingly alarming rates and where layoffs and cuts to benefits are causing greater poverty and insecurity for regular people,” said Dorter.

“Why not find out what some alternatives to the system are?”

The Montreal Anarchist Bookfair will take place at the CEDA centre (2515 Delisle St.) from May 29 to 30, and will be preceded by the Festival of Anarchy during the entire month of May.

This article originally appeared in Volume 30, Issue 30, published April 13, 2010.