Violence Breeds Violence

Anti-Police Brutality Day Plotline Plays Out Predictably

It’s pretty clear that this year’s Anti-Police Brutality demonstration on March 15 was absolutely brutal, and will go down in the books as one of the most needlessly aggressive protests many of our reporters have ever witnessed.

But now that the overturned garbage has been swept from the streets and the burning, chemical smell of tear gas has lifted from singed nostrils, there remain some important questions about what, exactly, happened on Thursday.

And, perhaps most importantly, why.

This was Montreal’s 16th Anti-Police Brutality march, which essentially means both the organizers and the Service de Police de la Ville de Montréal had over a decade’s worth of experience and understanding of this particular event to predict what was about to happen.

To a degree, you’d think, there exists potential to stop the violence and destruction before it even started—if peacekeeping was truly a priority of both parties.

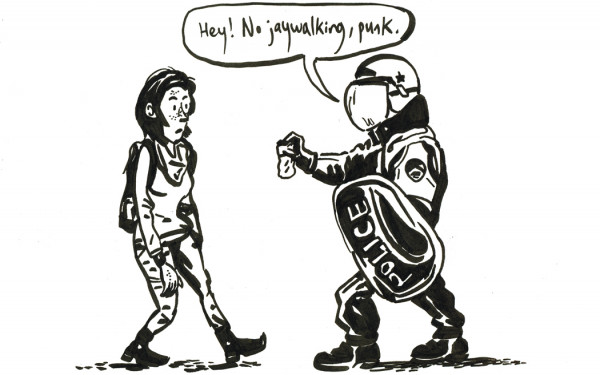

The annual formula is pretty straightforward and this year was no exception: It starts with good intentions in a public gathering, a demand for justice and a moment of silence to reflect on those victims who are killed by police in this town with impunity, and for survivors who are racially profiled, intimidated and harassed by the brotherhood on a daily basis.

Then the march sets out and, in all but two instances so far, it ends in violence.

There is also always speculation as to who started it.

Within a matter of blocks, things get shove-heavy. Someone pushes, someone else pushes back. Clashes take place, followed by a police kettle, followed by hundreds of arrests and an example made, again, of the ‘thugs and vandals’ terrorizing our city and thousands of dollars in property damage.

Or so the narrative, however accurate it may be, typically goes, year in and year out.

But since this has been going on for the better part of two decades, you might assume (or at least hope) experience would make it that an unfortunate broken-glass ending could be avoided.

So why does it keep getting more violent?

Chief of Police Marc Parent admitted at a press conference the morning following the riot that they had anticipated “lots of agitators and demonstrators who were there just to get their message out with acts of violence.”

And when you consider there were two helicopters accompanying hundreds of trained cops dressed and armed in full riot gear to ‘keep the peace,’ you would think taxpayers would demand it be kept.

The fact that they can’t sniff out and stop a few dozen protestors they perennially identify as bad seeds responsible for delegitimizing an otherwise democratic crowd is troubling, as they are paid generously from the public purse to be our best and brightest at crime prevention.

While the chief lauded his army of riot cops for doing a “very professional job” on the streets and their level of organizational tactics to “divide and conquer” went generally uncontested as being “effective,” anyone who was there knows that this protest in particular did not unfold so neatly.

It was four hours of chaos, of cat-and-mouse kettles and tense, terrifying standoffs in highly public spaces, often involving total innocents.

Centre-Ville, for all intents and purposes, became a sacrificial lamb of sorts.

As The Gazette reporter Monique Muise noted, “There didn’t seem to be any cops anywhere. Until they were everywhere.” But then they disappeared again—right in the heart of the downtown shopping district.

Why and how the SPVM could allow an increasingly agitated mob they were otherwise controlling with flash grenades, rushed lines and firm shoves to take over one block is beyond logistical rationale. By all accounts, they had it on serious lockdown—and then they didn’t.

Suddenly, the same forceful tactics that had worked on Aylmer St. and later at Berri Square seemed to evaporate in front of the Eaton Centre. And unsurprisingly, windows were smashed and an opportunity to destroy the conveniently unattended cop car that was left there was taken.

Of course the easy, kneejerk reaction might be to look at your TV and think, ‘Damn disrespectful kids,’ but what responsibility was there on the police to have never let it get into the downtown core in the first place, or to ever get to that point of needless destruction?

Ostensibly, they should have had the manpower and maneuvers to stop it. They certainly have the money.

Yet there we were: watching a cop car get flipped without any police presence in sight. If we believe the SPVM’s version of events, it doesn’t really make sense.

So remains the (almost) burning question: why would the SPVM leave the car knowing what they do about this riot each year? Why wouldn’t they intervene when a dozen active ‘vandals and thugs’ did what they said they had expected them to do, and deployed hundreds of police to stop?

The symbol of a burning cop car, whether fairly attributed or not, is synonymous with anarchy; it’s a calling card of dissent. This is also an image that serves the SPVM quite well, when you think about it.

Predictably, it makes the front page of all the papers (including our own) and is the first story up on the evening news. It justifies the police’s numbers, their often aggressive and increasingly armed protest tactics, and secures them a sizable operating budget.

But more critically, the cop-car calling card perpetuates a narrative many on the ground who see it with their own eyes know is more complicated than black and blue: it depicts both sides as either hooligans or heroes, depending on your politics.

Judging by online comments, it worked. Again.

Perhaps, though, the greatest tragedy of what we have come to expect on March 15 is that it undermines so many of the values that make the day important to celebrate and organize around to begin with.

So long as Anti-Police Brutality Day is recognized as an “Institutionalized Violence Day,” it moves a necessary call for peacekeeping reform further away from the public discourse and takes attention away from the heart of the issue.

Imagine what might happen if the police decided to delegitimize what they see as an unfair assessment of their jobs anyways—that they brutalize people—and weren’t present for this protest at all, or had less of a presence? What if they sent mediators to have an exchange with organizers and left the pepper spray off the streets?

Tough to say exactly what formula might work, but something is going to give if the formula doesn’t change.

Montreal has been doing this war dance for 16 years and, as March 15 demonstrated, it’s still not working to affect meaningful change. It hasn’t curbed police brutality or made many gains in public opinion.

There must be other methods to avoid excessive force from both sides that only add to the chaos and anger.

There must be a better way.

01_900_577_90.jpg)