Sew much more than trends

Swim and loungewear brand Em&May emphasizes sustainability and quality over making a quick buck

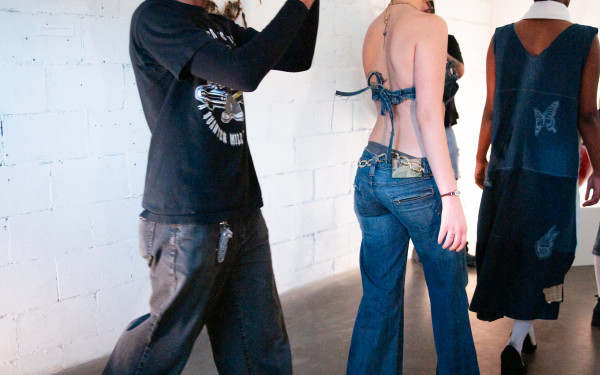

In her bustling Mile End studio, Emilie Pittman shapes more than just swim and loungewear.

As the founder and CEO of clothing brand Em&May, Pittman started her business six years ago and has championed slow fashion and sustainability since. First working alone, she created custom-sized swimsuits and posted them on Instagram for purchase.

Em&May has since expanded. Now with eight employees and nearly 30,000 Instagram followers, Pittman operates out of her studio, where everything is handmade. She emphasizes minimal waste in her business, offering 28 top sizes for swimsuits and a range of versatile pieces and loungewear to choose from.

Slow fashion emphasizes sustainable production and consumption, principles central to Pittman’s made-to-order business model.

“Made-to-order is such an easy way to have the least amount of waste possible and really just only create for the demand,” Pittman said. “Also, having that freedom of not having to produce beforehand and predict quantities [...] really gives us the ability to make things custom or make adjustments on pieces as we’re cutting them.”

Even so, the made-to-order route has its challenges.

“Ninety per cent of the time, the sustainable option is more expensive,” Pittman said, explaining that shopping sustainably means there are restrictions on the type of deadstock fabrics she can purchase. For her, sustainability comes first.

“That’s never something that we’re going to sacrifice for the sake of making more money,” Pittman said.

For instance, a similar sentiment is echoed by Concordia student Maya Gorinov, who criticizes tactics used by fast fashion brands to make a profit.

“Fast fashion follows micro trends and really capitalizes on it,” Gorinov said, “[and] is aimed at making the most money off of the consumer instead of providing them with something that will last.”

“I feel like the excuse of ‘It’s cheaper’ is not even accurate anymore, because prices are rising, and some fast fashion brands have the same pricing as us,” said Naëla Adjoualé, head seamstress and production manager at Em&May. “The only difference is, do you care about the ethical aspect of having [clothing] produced ethically by people who are actually paid properly to do that?”

“There’s always a person at the end of that machine,” Pittman added. Being aware of where individuals purchase things and who makes them is important to Pittman. For her, the “whole mentality of consumerism” in the fast fashion industry blurs people’s understanding of quality clothing.

Unlike many brands that charge more for plus-sized options, Em&May offers custom sizing at no extra charge.

“I would never want to be a company that somebody can’t buy from because of their body,” Pittman said. “I’m already cutting each piece individually because things are not batch cut. So what difference does it make for me to add a few centimetres onto your hem?”

Commitment to inclusion is key to Pittman’s brand and is part of what makes it so special.

When Adjoualé was studying to be a seamstress in France, her instructors made it clear that clothing designers must charge for everything, including customization. But working with Pittman, Adjoualé’s mentality quickly changed.

“To see the feedback of people saying that they never felt confident in swim[wear] before or an intimate,” Adjoualé said, “and that they found a piece with us that made them feel good and beautiful, it was so moving.”

Pittman values the versatility of the pieces they create. When creating their new “Fox” skirt, for example, the team started by cutting a big square fabric, and tying and pinning it in different ways to see what worked.

“We couldn’t understand where we were going with it,” Pittman said, “but then we found the most perfect plaid fabric ever, and it just all made sense.”

The Fox skirt can be tied and reshaped by the wearer and is one of their most versatile pieces yet.

“Giving a piece multi-purposes is a better bang for your buck,” Pittman said. “And everybody loves pockets in skirts and dresses. People love to wear things in different ways.”

As a self-identified “chronic mood-boarder,” Pittman finds inspiration from many places.

“It’s not garments, necessarily, that I’m looking at. It’s tiles, prints; we are looking at all these different things,” Pittman said.

And sometimes inspiration doesn’t make sense—but that doesn’t mean Pittman and Adjoualé don’t embrace it.

“For the collection that’s coming out, we called it ‘Rogue,’” Pittman said, explaining that many of the pieces came from a medley of ideas that didn’t fit in their previous collection. “It just kind of happened out of nowhere,” she said.

Creative chaos is typical for Pittman and Adjoualé, as they describe their process as making sense of the senseless.

“We also love the aspect of, ‘Oh shit, I’m making this cool chaos, and it’s right now, and that’s just what I’m doing,’” Pittman said. “We make our own rules.”

For folks wanting to get into slow fashion, Pittman and Adjoualé suggest thrifting, because you can find original pieces from the eras they originate from, instead of the new remakes, according to Pittman.

With fast fashion remaining a multi-billion dollar industry and companies like Zara introducing new styles almost every week at compelling prices, overconsumption has become a consequence of low-priced, trend-driven clothing.

Transitioning from fast to slow fashion may be difficult, according to Adjoualé.

“You can’t jump from one to the other fully,” she said. “Stay educated on the subject. The more you read about how your clothes are actually made, the more people realize, [...] ‘It doesn’t align with my values..’”

Pittman added, “[Look at] what kind of fibres are on your body. Look at the tags.”

When it comes to affordability, Pittman recognizes that many slow fashion brands may be out of financial reach, especially for Montreal’s large student population, but she said that “slow fashion brands have sales, too.” The two believe that if people keep their eyes peeled for slow fashion brands that align with their values, they’ll find them.

And for folks who may not be able to support slow fashion brands yet, Adjoualé has some advice.

“Maybe you can’t invest right now, but somebody around you can,” she said. “Even just to share and have people more aware that these brands exist, and that there’s an alternative to fast fashion, is also a free, good way to support.”

This article originally appeared in Volume 45, Issue 6, published November 19, 2024.