The Mental Battle of Injuries in Sports

How Injuries Can Affect an Athlete’s Mental State

Injuries in sports are anything but surprising. From the the amateur level to professional leagues, whenever there is physicality, incidents are inevitable, whether minor or major.

These injuries, however, don’t just occur on the physical level. Several studies have shown that athletes are prone to experience mental health struggles like depression or anxiety at some point following their injury.

When an athlete gets injured, they are immediately overwhelmed by an adrenaline rush followed by the stress of not knowing what has just happened. Whether the incident is minor or major, they wonder if they’ll make it back. Or are they out indefinitely? A series of thoughts and fears happen instantly.

How important is an athlete’s mental health while going through the recovery process? How important is it to create a safe environment for athletes to speak up about how they feel following an injury?

Looking at things more thoroughly, it’s not a simple matter.

Last season during the fall semester, Concordia Stingers women’s basketball shooting guard Aurélie D’Anjou Drouin tore ligaments in her right ankle before completely dislocating her left ankle two months later.

“At that time, I thought it was over for me,” she said. “After the game, I was really emotional, I thought I had broken up with basketball for good.” Drouin said her confidence levels went downhill after two back-to-back injuries. She wasn’t able to walk without crutches for two months and it took her an extra month before she was able to trust her body again.“The way we’re coached is very beneficial to us when it comes to remaining strong mentally. It was due to the way I was coached that I got back to playing shape,” said D’Anjou Drouin.

An open and honest relationship with her team and its coaching staff let D’Anjou Drouin keep a positive mindset throughout her long recovery process.

The first person to respond to the athletes upon injury is the athletic therapist in most cases. Therapists are crucial to the athlete’s well-being from the moment they get hurt to the moment they are fully recovered.

NBA Brooklyn Nets assistant athletic trainer Jana Austin elaborated on the importance of her job as a therapist and point of first contact after an injury. Not long ago, she assisted Nets’ shooting guard Caris LeVert as he left a game with a gruesome right leg injury on Nov. 12.

“Depending on the severity of the injury, the ones that are more long-term such as major injuries usually harbour the emotion of denial,” she said. “That definitely is something that you see early on. The best thing is to educate the players about their injury and the rehab process.”

Austin articulated the importance of being honest but optimistic with players at the same time. That allows them to feel some positivity.

“There are going to be good days and bad days but you as a clinician have to make sure you stay neutral and keep coming with the positive reinforcements,” she continued.

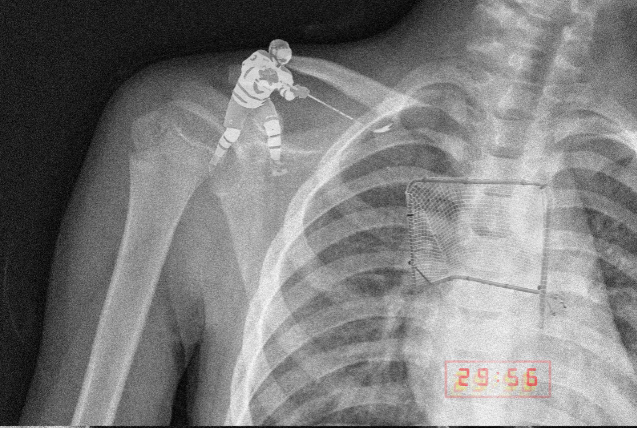

Stingers men’s basketball forward Sami Ghandour also dislocated his shoulder during last season’s finals against McGill.

“At first, I was in total shock when I found out that I would need surgery and miss six months of playing basketball. It seemed unreal. I had a lot of thoughts in my head. Like, ‘Would I ever get back to being how I was before getting injured?’” Ghandour said.

Fortunately, Ghandour’s father, who had previously dealt with injuries in his former kick-boxing career, was supportive of him through his rehabilitation. His dad reassured him that after surgery, his shoulder would be much better and that it wouldn’t be his only season as a Stinger. Ghandour credits his father for helping him tremendously through the recovery process.

“It hurts to watch something that you love doing so much but you physically can’t do it. Sometimes, I would think to myself ‘is this it? Like, will I ever be able to play again? Could this be the end of my career?’” —_Sami Ghandour_

“It hurts to watch something that you love doing so much but you physically can’t do it. Sometimes, I would think to myself, ‘Is this it? Like, will I ever be able to play again? Could this be the end of my career?’” Ghandour continued.

The second-year forward got back to the floor in playing shape in mid-November and ever since, he has been feeling better and able to run the floor.

Former Canada national basketball team player and Concordia Stingers men’s basketball assistant coach Dwight Walton is accustomed to the world of injuries.

Walton was first introduced to dealing with physical distress back in 1991 at the age of 26 when he had to have his left knee operated on. He was with Canada’s national team at the time. Walton woke up one morning and could not bend his leg. When he went to the training room, the therapists told him that he would have to undergo surgery.

All of Walton’s injuries, however, are different in the sense that they did not occur while playing. “My injuries are more wear and tear,” he said. “I’m a sports guy and my body just started [weakening].”

Throughout his basketball career, Walton underwent a total of five knee surgeries, three on his left knee and two on his right. Alongside the knee injuries, he also previously dealt with a dislocated shoulder and a broken jaw.

The road of distress didn’t end there for Walton. At the age of 35, he found out he had arthritis but decided to continue playing. As a result his body started breaking down. In June 2017, he was obliged to undergo a hip replacement followed by another replacement in the summer of 2018.

As per exposure to rehabilitation, Walton put a lot of emphasis on not taking any alternate routes to getting back into playing shape.

“You may take shortcuts to get back, you may feel okay but you’re not truly 100 [per cent]. As a result of that, more surgeries occur, and because we’re athletes we have pride. We’re competitive. We’re strong. We’re also taught to be tough.” said Walton. “But when we’re tough, we’re not smart either. I came back before I was supposed to, that was my competitive drive, I wanted to keep my spot on the team so nobody else would get it.”

Sports culture has always been known for being “tough.” Everybody is there to win.

When speaking about toughness in sports, the coach explained that his hope when dealing with players is that he and the coaching staff try to get as close to them as possible.

“Unless you open up to us as coaches, we don’t know what you’re going through off the court. We don’t know unless you tell us,” he said.

Sadness, isolation, disengagement, irritation, frustration, sleep disturbance and changes in appetite are all common emotional responses that injured athletes go through.

According to Walton, athletes often hear, “‘Stop being soft, stop being a wimp, stop being weak mentally.’ It’s an unfortunate part of the culture,” he added. “I’ve been hearing it since I’ve been an athlete. It’s difficult for people to come out and talk about their personal lives because they don’t want to come across as being soft.”

Walton explained that when dealing with mental illness, athletes are automatically considered weak, when that couldn’t be farther from the truth.

“Our job is also being a [psychologist],” he said, explaining the need for coaches to be there for their players when times get tough.

While not every institution has the proper resources to assist athletes through rehabilitation, the care of coaches and therapists, not only physically but mentally, proved to be welcome help for athletes like D’Anjou Drouin and Ghandour. For injured athletes, the long road to recovery travels through the mental just as much as the physical.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)