The Future of MIGS Uncertain

Concordia Research Institute Up for Renewal

The future of the Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies at Concordia seems to be resting in Dr. Max Bergholz’s hands, and he’s not sure what to do with it.

Currently, the institute, which is known as MIGS, is up for renewal as a certified research centre at the university. Its previous certification, which began in 2011, ends on May 31. If he chooses so, Bergholz can apply for the renewal of MIGS as a research institute and become its interim director.

A meeting between him, the Dean of Arts and Science, and the History Department Chair has been scheduled on March 10 to discuss what his choice will be. His uncertainty about continuing with MIGS, he says, is because there’s been a lack of peer-reviewed academic research published over the past few years.

“If I were to become interim director, I would need the space to build this place into a research institute,” he says. He explains that to do this, he would need full control over the budget.

Bergholz is a full-time professor from the History Department. He’s been at MIGS since 2010 and became its assistant director in 2014. MIGS’ mandate is to “conduct in-depth research and propose concrete policy recommendations to resolve conflicts before they degenerate into mass atrocity crimes.”

In those seven years, Berholz has published an article in the prestigious American Historical Review, released a book on ethnic violence in the Balkans in 1941, and received the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation Research Grant, a feat no other Concordia professor has achieved. He says most of his work cannot be attributed as products of MIGS.

“One will say I haven’t done much research [for MIGS] but I haven’t been given the resources to do so,” Bergholz says. The professor’s introduction to Concordia and MIGS came about in 2011 because of the James M. Stanford Professorship in Genocide and Human Rights Studies. Stanford, an outside donor, pledged $500,000 over five years to hire a new professor to be groomed as the future director of MIGS.

Enter Bergholz. “We hired the right, terrific guy in Max,” says Dr. Frank Chalk, the director and co-founder of MIGS.

The professorship stipulated that in addition to an annual base salary of approximately $80,000, $15,000 would be allocated for a graduate fellowship on genocide studies, as well as $5,000 for Bergholz’s personal research expenses each year. Bergholz never saw the money for graduate fellowships and has never had a graduate student do research as part of MIGS.

“Students will go to universities where they’re funded,” Bergholz says, explaining that graduate students have asked about doing a fellowship at MIGS with him, only to find out the financial situation of the institute. Funds have instead mainly gone towards paying salaries for the two full-time staff employees—which has caused MIGS to run deficits in the past few years.

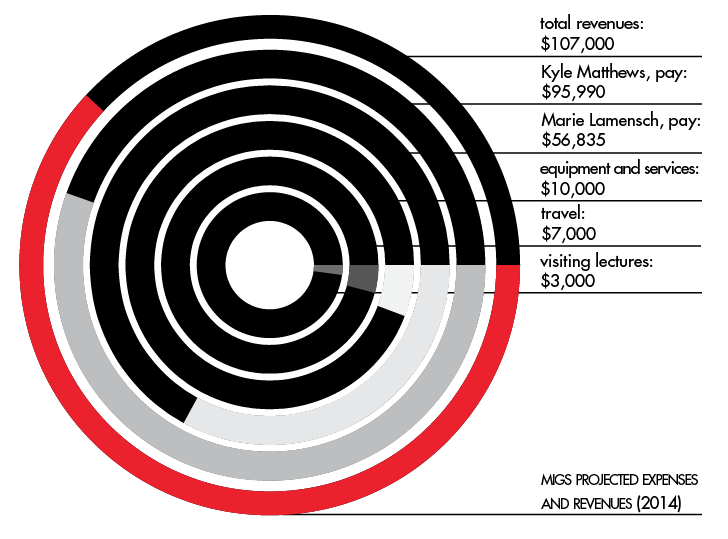

Annual salaries cost approximately $150,000, but revenues only total around $107,000. The university gives MIGS $30,000 a year, while the rest of the revenue comes from private donors. One of the full-time staff members of MIGS is Kyle Matthews, who earns approximately $90,000 a year. The other staff member is Marie Lamensch.

Matthews first joined MIGS as the lead researcher of a project called Will to Intervene in 2008, and then was hired full-time as the senior deputy director in 2011. He is not a professor at Concordia. Last October, he briefly took on the role as director of MIGS, the position Bergholz was supposed to be groomed for.

His time as director lasted about a week. On Oct. 25, university administrators organized a ceremony in honour of Dr. Chalk, there since the start of MIGS in 1986. At the event, it was announced that Matthews would succeed Chalk as director.

On the next day, Concordia NOW, the university’s press release service, published an article announcing Matthew’s appointment as director. The article was retracted soon after and re-published on Nov. 1 stating that Matthews actually became the “executive director” of MIGS.

Confusion arose as it emerged that procedure had been broken with the original announcement. Under the Policy on Research Units from the Office of the Vice-President, Research and Graduate Studies, it states that to be a “director” of a Concordia research institute, one must be a full-time faculty member at the school. Matthews doesn’t meet this criterion.

“We made a mistake,” says Justin Powlowski, the interim Vice-President of Research and Graduate Studies. As well, to appoint a new director, the policy states a search committee must be formed and evaluate nominations from different candidates, which also didn’t happen.

Powlowski says that when Chalk privately began making known his intentions to step down as director in recent years, meetings were held with Matthews and Bergholz, looking into replacing him. Internally, Powlowski says, there was a lot of pressure to make an announcement about a successor.

“In order to give [Matthews] more maneuvering room to talk to donors and start doing more proposals, we needed to make some sort of announcement,” he says, explaining the reasoning behind the ceremony.

Dr. Bergholz says he didn’t know about the ceremony or the appointment beforehand. Dr. Chalk himself says he only became aware that they were holding a ceremony for him a few days before. “I was never offered the opportunity to invite people to what turned out to be a reception to honour my career,” Chalk explains. “It’s really odd.”

The failure in procedure became public after Dr. Ted McCormick, another history professor, began posting about it online in private forums of full-time faculty at Concordia. The History Department, including McCormick and Chalk, unanimously passed a motion asking for a public disavowal and removal of Matthews from the position of executive director and that an investigation be launched to determine how everything unfolded.

The department cited the break in procedure as cause for their motion and further stated that the four history professors who sit on the Board of MIGS were not consulted about the appointment. According to most accounts, the Board hasn’t met since MIGS became a certified research institute in 2011.

“We made a mistake,” —Justin Powlowski, interim Vice-President of Research and Graduate Studies

McCormick said they invented the position out of thin air. “There’s no policy or procedure associated with it.” Despite the change in title, he adds, it’s clear to him that Matthews still runs the show at MIGS.

Matthews says his job hasn’t changed much since he transitioned from senior deputy director to executive director. The change has allowed Dr. Chalk to begin doing more research, Matthews explains, while he has greater control now on the managerial side of the operations.

The Future of MIGS, the Future of Concordia

The Will to Intervene is the project that allowed MIGS to grow its reputation worldwide, according to Matthews. The goal of the project was to create a policy report that “recommends practical strategic measures to government officials, legislators, civil servants, non-governmental organizations, advocacy groups, journalists, and media owners and managers in Canada and the United States to raise their capacity to prevent mass atrocities overseas.”

In 2010, former US President Barack Obama adopted two of the project’s recommendations into his administration’s plan for national security. MIGS eventually published the report as a book in 2010.

“That’s not advocacy—that’s scholarly research,” Matthews says about the work of the project.

Matthews regularly appears in local and national media to comment on human rights issues facing the world. Social media also plays a big part in the operations of MIGS. Its Twitter feed is active daily, and one of the institute’s main projects right now is the Digital Mass Atrocity Prevention Lab. The goal of the lab is to research how extremism spreads online and to recommend policies to counter it.

“I would call it advocacy without research,” Bergholz says, emphasizing academic research must be peer-reviewed before publication. “[…] to advocate on behalf of the university you have to have done serious research.”

Professor McCormick echoes this, saying that MIGS doesn’t have an academic program associated with it, doesn’t produce any type of academic publication, or go after peer-reviewed research grants.

“What they do a lot of is have Kyle Matthews talking to the local media about whatever latest event is happening,” he says. “They have a public profile.”

While there is only one PhD candidate from Concordia listed as a fellow of MIGS right now, Matthews says his goal is to raise more donor money to fund graduate research. The institute has hosted 73 interns during his time there, many of whom came from Concordia undergraduate programs like journalism and political science, he adds.

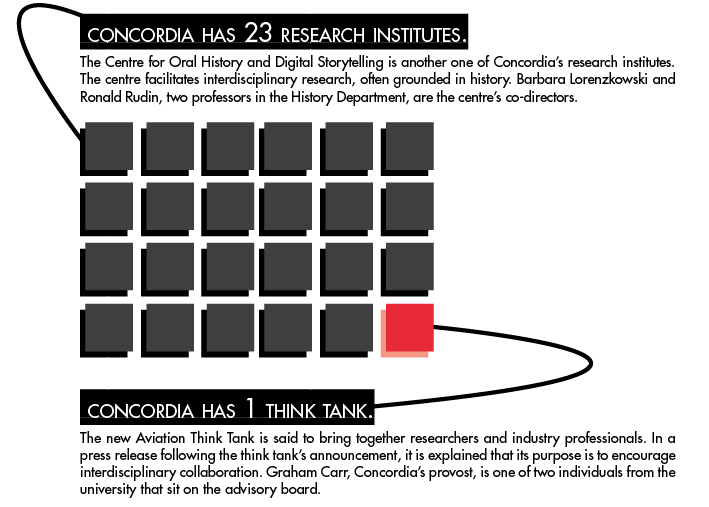

If Bergholz leaves the upcoming March 10 meeting with the decision that he will not pursue a renewal of MIGS as a research institute, then it appears the institute would become a “think tank” to accommodate the current setup they have. How a think tank works procedurally isn’t clearly defined anywhere or by anyone.

“We’ve been thinking about other ways that we could potentially accommodate the kind of things that Kyle does, perhaps in a different kind of structure,” Powlowski says about the think tank model for MIGS. The model was created as part of discussions for one of Concordia’s nine Strategic Directions, “Double Our Research.”

The university administration basically wants to decertify MIGS as a research institute in favour of this think tank model, according to Bergholz, and he’s not sure why. “Financially it’s unviable in its current form,” he says. “Somehow it will become viable as a think tank.”

_900_600_90.jpg)

_1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)