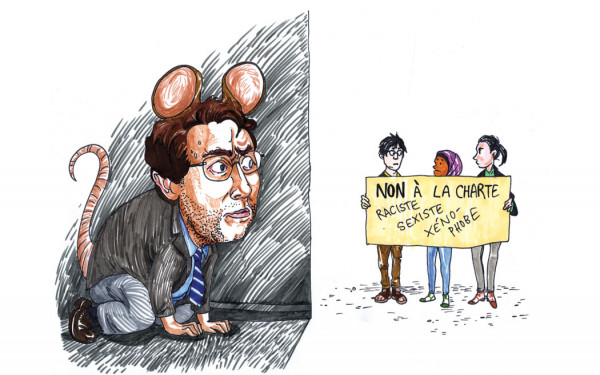

Is the Charter of Quebec Values a Feminist Initiative?

Panel Discusses Implications of Bill 60

Pearl Eliadis minced no words when she stood in front of roughly 60 people last Thursday and stated that, “Bill 60 utterly fails to achieve gender equality. It utterly fails to do anything for secularism and it turns the whole concept of religious freedom and secularism on its head.”

The Montreal-based human rights lawyer was one of four panelists at a discussion on Bill 60—also known as the Charter of Quebec Values—that sought to examine the proposed charter from a feminist, queer, LGBT or racialized view.

The panel discussion was organized through the combined efforts of the Simone de Beauvoir Institute, the Concordia Student Union and the Centre for Research-Action on Race Relations, and featured panellists in a variety of fields, from communications to law. It was not explicitly framed as a pro/con debate on the charter, but rather sought to explore the implications of such legislation if it was passed in Quebec’s National Assembly.

The proposed charter is less about state secularism than it is about the fear of political Islam, according to Eliadis, who also said it does nothing to actually address such concerns.

“I find it hugely ironic that a government that purports to advocate for gender equality should be supporting a provision that is going to have a systemic, systematic and substantively negative impact on the very women that it says it wants to promote social equality [for],” she said, adding that though the bill is designed to achieve gender equality, all evidence so far suggests it will do the exact opposite.

Eliadis was not the only panellist who expressed concern with the claims of the governing Parti Québécois that their bill would promote gender equality. Sirma Bilge, a sociology professor at the Université de Montréal, added that the sectors that would be affected by the bill—such as the users of government services and employees of the provincial government—are largely made up of women.

“These are the sectors in which women are overrepresented as childcare workers, […] health professionals, social service providers and so on. So it is not an overstatement to suggest that hijabi Muslim women will be the most heavily affected group by the restrictions of the conspicuous religious symbols,” Bilge said.

The PQ has maintained that the charter would help to further the feminist cause, but those present at the panel overwhelmingly disagreed. The government recently got into hot water with the friends and family of late Quebec feminist Madeleine Parent after using her name alongside other figures of provincial feminism, such as Jeanne Mance and Marie-Claire Kirkland, in an attempt to show how the legislation is aligned with feminist ideals. Parent’s friends and family criticized the decision to include her name, saying that she would have never given her support to such a bill.

Present at the talk was Parent’s longtime friend and neighbour Cynthia Kelly. According to Kelly, the PQ’s decision to include Parent’s name in the bill represented a view of the late feminist that is “frozen in time.”

Kelly sees the inclusion of Parent’s name as indicative of the feminist undercurrent of the charter, where the link is made between the quest for gender equality pursued by feminists and the quest for the same equality by the government.

According to Kelly, the government’s belief that “no religious accommodation should be made for public service employees if that accommodation interferes with gender equality” led them to conclude that banning the presence of overt religious symbols could be seen as preserving gender equality, thus legitimizing the idea that the charter represents feminist values.

“Underpinning the government’s logic is that religious symbols are inherently disempowering to women and foster a serious form of inequality between men and women,” Kelly continued, stressing that this idea relies on a stream of feminism that views all religions as non-egalitarian and on the idea of “women as a universal group and religion as a universal threat,” ignoring complexities that exist within the category of “woman.”

Bilge referred to the type of feminism the provincial government is using to promote the charter as “a kind of feminist nationalism.”

“It’s a moral crusade to achieve, in the name of gender equality, the discrimination and marginalization of other women, those wearing headscarves,” she said. “Femi-nationalists have been among the key architects of an incoming sense in Quebec—the Muslim peril.”

“If this type of initiative had been created or instigated by somebody who was not a parliamentarian protected by parliamentary privilege, they would be subject to hate speech laws.” —Pearl Eliadis, human rights lawyer

Others present, like Concordia communications professor Yasmin Jiwani, echoed this idea of the “Muslim peril.” She explained that the proposed charter essentially legitimizes the racism that already exists under the surface in Quebec, and that those in charge of the bill are “hijacking feminist principles.”

“It’s making feminism do its dirty work,” Jiwani said, “and that dirty work is the containment of women, but it’s also neutralizing what it sees as a threat.” It’s an idea that tied into Bilge’s words on femi-nationalism, where the fear of the “Muslim peril” compels people to try and squash what they perceive as a danger to society.

There have been increasing reports of violence against Muslim women since the charter was first formally proposed in early September. Ultimately, panellists argued that while the charter is framed as an attempt to achieve secularism in the province, in reality it is simply an attack on Muslim women. According to Jiwani, the proposed ban on religious paraphernalia like kippahs or turbans are merely added in to try and legitimize the ban, but that “as a strategic tool, it definitely goes after Muslim women,” she said.

“This charter, what it does is mandate state-level violence. […] It keeps the women at home, where they’re the most vulnerable to intimate forms of violence,” Jiwani said, referring to the fact that the majority of assaults occur when the perpetrator is known to the victim.

The legality of the bill was also questioned, with Eliadis stating that the bill is ultimately a form of profiling.

“It’s a form of religious profiling, it’s a form of ethnic profiling, it’s a form of racial profiling that has the double-whammy of specifically impacting and targeting women of minority backgrounds,” Eliadis said.

“If this type of initiative had been created or instigated by somebody who was not a parliamentarian protected by parliamentary privilege, they would be subject to hate speech laws,” she continued.

“The demonstrable effects of this bill have been to incite hate—hate in the streets, hate in the metros, hate online.”

_900_597_90.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)