Looking at Society through a Philosophical Lens

Charter of Values, Gentrification Among Topics Discussed at Three-Day Philopolis Conference

The City of Saints became the City of Knowledge over the weekend when Montreal was home to Philopolis, an annual three-day conference that brings together members of the public as well as students and professors from Montreal’s four universities to discuss societal issues.

Issues ranging from a post-capitalist economy to breakdance culture, as well as their philosophical implications, were topics of discussion at this year’s edition.

“I think Philopolis, now that it’s reached its fifth year, is definitely here to stay,” said Gabriel Larivière, a Philopolis organizer and philosophy student at McGill University. “I think for a lot of students, especially for undergraduate students, it’s a good opportunity to do a talk or presentation similar to what graduate students and professors usually do.”

The conference began at the Université du Québec à Montréal on Friday before making its way to the Université de Montréal on Saturday. The closing event of Philopolis, held on Sunday at McGill, was a panel discussion on secularism and the state.

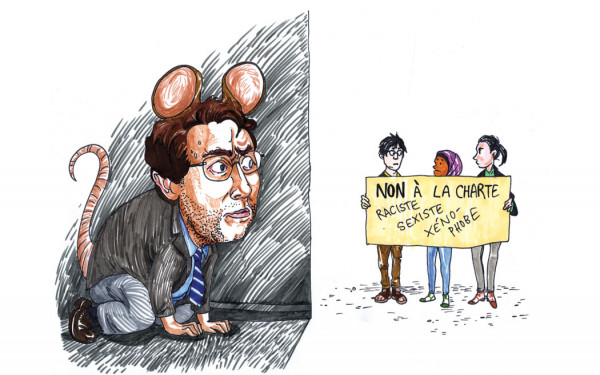

The event focused on the philosophical and practical ramifications of the proposed Charter of Quebec Values, also known as Bill 60. If passed, the legislation would ban public sector employees from wearing conspicuous religious symbols including turbans, hijabs and large crucifixes.

Marc-Antoine Dilhac, a philosophy professor at U de M, started off the discussion by saying that laïcité, or secularism, is an ideological practice used by those in power as a manner of social organization.

He explained that secularism, established after the French Revolution as “liberty of conscience,” was a way of protecting the state from the Church and the Catholic majority.

Therefore, the idea that “the state protects secularism, the state protects religious minorities” is inaccurate, he said.

“It’s in this context that secularism takes a defensive form; [it’s] certainly not when it involves dealing with the issue of religious minorities who don’t have institutionalized power,” he added.

Panellists agreed that the charter’s effect on women who wear a hijab or burqa would be not only detrimental but contradictory to its supposed intention to affirm equality between men and women.

“It’s a bizarre conception of equality which excludes women from the workplace while telling them, we’re giving you equality,” said Daniel Weinstock, law professor at McGill.

Yara El-Ghadban, an anthropology professor at the University of Ottawa, drew attention to Article 12 of the charter, which protects the right of doctors to refuse to perform medical services that contradict their personal convictions, such as abortion.

El-Ghadban said that this is in opposition to the struggle of women to have the rights all people should have, especially the right to control their own fertility. There is an inconsistency between the purpose of the charter as stated by the Parti Québécois and the effects it would actually have, she said.

Michel Seymour, another philosophy professor at U de M, added that forbidding women from wearing a hijab while performing a public function with the justification that the veil is a symbol of female oppression is counterintuitive to the empowerment of women studying law or medicine who wear it.

“The charter, rather than helping religious minorities integrate, creates a division between the Catholic majority and religious minority, between ‘us’ and ‘them,’” he said.

Experiences of Gentrification and Resistance

A talk about gentrification on Saturday at U de M took on minority rights from a different perspective. The talk’s first speaker, Marie-Ève Desroches, is an urban studies student at UQAM and spoke notably of “the right to the city.”

“The objective which drives the right to the city is that the city again becomes a reflection of [the people’s] needs and not a simple instrument of the capitalist system,” she said.

Desroches explained that globalization led to “the neo-liberalization of space.” This neo-liberalization took the form of gentrification, the phenomena which inevitably begins with artists moving to a neighbourhood for the cheap rent and ends in gluten-free cafés and expensive condo buildings.

The idea of public space was brought into question in the talk. Desroches said that while a large portion of the population in central neighbourhoods such as Ville-Marie are homeless or in other ways marginalized, their access to public space is very different than that of powerful people who often don’t even live in the neighbourhood.

“There’s a deficit of democracy for the population which lives in the periphery, and have less influence in the central neighbourhoods,” she said. “The central neighbourhoods become a global issue, and the populations that live there have very little influence in Montreal—for example, the mayor of the borough of Ville-Marie is equally the mayor of the city.”

Desroches added that although there are people developing good initiatives to ensure they are better represented politically, they often lack resources and aren’t sufficiently supported financially.

The second speaker, UQAM student Denis Carlier, said that “public space” had disappeared and that the very concept of public space was institutional and discriminatory.

He gave the example of an ambitious project in 1989 to put a municipal park in Berri Square with the official objective of revitalizing the neighbourhood but which had an underlying goal of pushing out the many homeless people there with rules that restrict people’s access to the park at night.

“What’s interesting in this example is that in the end, the exclusion was a relative failure, in spite of the police presence, because the dominant population in Square Berri is still the homeless population,” he said.

_900_600_90.jpg)