Indigenous Researcher Kicks Off New Concordia Lecture Series

Kim Tallbear Discusses How Colonization Instituted Monogamy Into Indigenous Communities

With not-so-light topics like sex, settlement and nature, the Future Imaginary Lecture series is off and running at Concordia University.

Hosted in collaboration with Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace, the Future Imaginary Lecture series is an initiative intended to provide a public forum where “innovative Indigenous thinkers, makers and activists can come and share their visions of the future,” according to Jason Lewis.

Lewis is one of the co-founders of the Initiative for Indigenous Futures research group, a university and community partnership organization which explores and develops indigenous visions for the future.

Originally from South Dakota, Kim Tallbear, was the first speaker for the series which debuted on Friday. She is the Canadian Research Chair in Indigenous Peoples, Technoscience and the Environment.

She is also an associate professor in the faculty of Native Studies at the University of Alberta. Tallbear’s work directly challenges what she calls “compulsory monogamy and hetero/homo-normative couple-centric marriage,” from an indigenous consideration.

Her research focuses on how European settlement disrupted diverse forms of relating, sexuality, family and community practices.

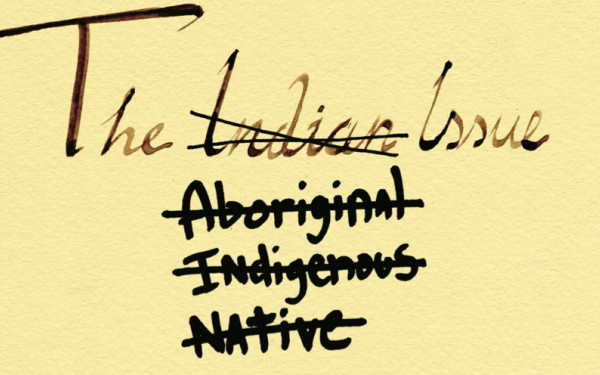

She explained how settler categorization of sexuality and the management of resources was “entangled with the state management of women, children, slaves, Indigenous people and other-than-human bodies,” meaning land, animals and water. Restrictive colonial naming and enforcement dictated how bodies and cultures were controlled.

Tallbear revealed how, according to research, “monogamous marriage was not a dominant worldview until the late 19th century.”

Monogamy, she explained, was forced upon native communities, established as a part of the national agenda, to “guard the way of life.” Tallbear credited much of this research to thinkers Sarah Carter, Angela Willie and Kim Anderson.

Not only did Christian ideals get enforced in Indigenous communities, but sexologists also played a crucial role in shaping cultural belief and practice, Tallbear added.

“Their more evolved, enlightening and individualistic coupling was juxtaposed with the savage others who were their foils,” she said, referring to the standards set by sexologists.

Tallbear quoted a familiar phrase that still reverberates deep in the psyche of Indigenous communities, “Save the man, kill the indian.” Part of the process of “saving the man from savagery” meant coercing Indigenous peoples into couple-centric nuclear families.

Tallbear’s reasearch examines how enforced marital practices especially targeted women’s power. “It tied land tenure rights to heterosexual one-on-one, life-long marriages, thus tying women’s economic well-being to men who controlled private property,” she said.

“We must oppose a system of compulsory settler-sexuality and kinship that mark Indigenous and other relations as deviant,” – Kim Tallbear

Finding Help From Extended Kin

Her work stretches as far back into the memories of her relatives and ancestors, to a time when her Dakota community engaged in a type of communal “relationality” with extended family—loosely translated to the Dakota word “tiospaye.” Indeed, this type of extended familial consideration involved strong bonds of kinship, support and intimacy.

“There was no such thing as a single mother,” Tallbear explained, quoting Cree-Metis scholar Kim Anderson from her book A Recognition of Being: Reconstructing Native Womanhood. “Native women and their children lived and worked in extended kin networks.”

Tallbear herself experienced tiospaye in her childhood. Her mother left South Dakota at 28-years-old to find work in Minneapolis. She took her two youngest children and left Tallbear and her younger sister in the arms of her extended kin, her grandmother.

Under the weight of a conception of a “normal” ideal middle-class nuclear family, Tallbear recounted feeling shame and regret. Her family didn’t mirror the restrictive colonial standards placed on her community and she thought her family’s alternative narrative was a result of Indigenous peoples’ failure to conform.

Throughout her life, Tallbear has come to realize that these notions of a healthy family do not always serve Indigenous peoples, both individually and collectively.

Tallbear explained how in the Dakota community, relationships and marriages used to be alive in a different way. “Before settler imposed monogamy, marriages helped forge Dakota kinship alliances,” she said. “Divorce for both men and women was possible, more than two genders were recognized and there was an element of flexibility in gender identification.”

Though fiercely critical, Tallbear was not short of solutions. “We must oppose a system of compulsory settler-sexuality and kinship that mark Indigenous and other relations as deviant,” she said.

Her work encourages advocating for policies like universal health-care and easier child-custody arrangements, non-monogamous and “more-than-couple bonds that support a more expansive definition of family,” she said.

Although married at 30, Tallbear’s partnership took on a life of its own. “Affectionate and supportive friendship with the partners of my partners is a key benefit of ethical non-monogamy,” she shared.

Tallbear asked, “How does the different sustenance I gain from multiple lovers collectively fortify me and make me more available to contribute in the world? If I am richly fed, what and who am I able to feed?”

The next speaker of the Future Imaginary lecture series is Allen Turner, “an American storyteller, game designer, author, and dancer with a lifelong love of storytelling, games, and play.” He will be speaking at Concordia on Nov. 11.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

ED1(WEB)_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)