The nuances of cannabis legalization

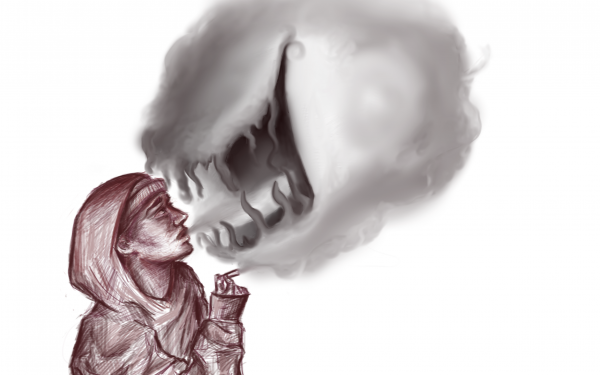

Stigma around cannabis continues to plague its full-fledged legalization

A five-leaflet plant known by many names, with a deep history mired in controversy, has been shaping cultures and societies far beyond its recent century of prohibition.

A five-leaflet plant known by many names, with a deep history mired in controversy, has been shaping cultures and societies far beyond its recent century of prohibition.

On Oct. 17, 2018, Canadians awoke to a new era as cannabis was legalized, making its return to the public sphere after being banned in 1923. Since then, the stigma surrounding cannabis has persisted, creating a positive face-value effect, but an underlying apprehension.

Cannabis has a rich history, with studies indicating its use in Central Asia dating back 11,700 years. Although recreational use primarily relies on the compound THC for its cerebral high, hemp served practical purposes such as making ropes and nets.

Additionally, cannabis, specifically that with low THC content, was used among Indigenous and First Nations people for thousands of years. Earliest evidence suggests hemp was used by the Mound Builders of the Great Lakes and Mississippi Valley.

In India, myths described cannabis as a divine ingredient. Known as ‘Vijaya,’ cannabis was recognized for its ayurvedic medicinal benefits, alleviating pain, nausea, anxiety, hunger and sleep issues for thousands of years.

Yet in the 1900s, cannabis became a subject of growing controversy. Its use became increasingly stigmatized due to racist attitudes and legislation, despite its cultural and medicinal background.

The racial and political climate surrounding cannabis deteriorated under Harry J. Anslinger, the first commissioner of the U.S. Federal Bureau of Narcotics, who launched a campaign against the substance. By using the term “marijuana” to link it with Mexican immigrants and associating it with jazz music—an art form largely associated with Black artists—Anslinger fuelled racial biases and unfounded claims about its criminal influence.

Lailaah Wilson, a 23-year-old Montrealer of Caribbean descent, touched on the association that cannabis has had with the Black community.

“Weed has been smoked by everyone for God knows how long,” Wilson said. “I just think a lot of times, it was just a way for white cops to unfortunately criminalize and lock up a lot of Black youth.”

This association became a stereotype, one that is rooted in efforts to single out Black and Latin Americans. With that effort, Ansligner created the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, which imposed strict regulations on cannabis and hefty fines. Cannabis subsequently became a Schedule I drug in the United States in 1970 under the Controlled Substances Act, meaning cannabis was classified as a drug which had no acceptable medical use and was defined as having a high potential for abuse.

“Criminalization, it really puts a negative connotation towards weed in general and to the Black community in general,” Wilson said. “It really put a lot of people in jail for more than decades for crimes, with reasons that are not warranted.”

Growing up in a Trinidadian family, Wilson was used to seeing weed around, much like how alcohol is a normal staple in other households.

Despite legalization, Wilson said the stigma surrounding weed hasn’t disappeared.

Similar to the U.S., Canada’s federal government has not always had a favourable position with cannabis either.

Former Canadian prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King added cannabis to the Act to Prohibit the Improper Use of Opium and Other Drugs to criminalize the herb. The act never actually passed through parliament, but it still became law. At the time, few Canadians knew what cannabis was, and it wasn’t until 1932 that the first seizures of cannabis occurred. Possession charges weren’t made until 1937, 14 years after the substance had been criminalized.

Since its return, weed has brought a new influx of money to the economy. According to a 2021 Deloitte study, Canada saw $11 billion in cannabis sales between 2018 and 2021.

Christopher Mennillo, CEO of Prohibition, a Quebec-wide shop selling cannabis paraphernalia, emphasized the economic impact of legalization on his stores; it led to a noticeable uptick in sales. However, it also brought new legal challenges, particularly in Quebec.

“A bunch of products had to go in the garbage,” Mennillo said.

According to the Quebec Cannabis Regulation Act, sellers are prohibited from selling items with cannabis-related logos or slogans in the province. Before legalization, selling these products wasn’t an issue.

Mennillo also noticed a negative shift in the public's education regarding cannabis.

“The education toward the public was a little bit better pre-legalization because the Cannabis Act didn't exist and there was nothing particularly illegal about selling [products related to cannabis],” Mennillo said. “For example, a book on cannabis or how to consume cannabis or how to grow cannabis. All of that was fine, but now post-legalization in Quebec, all of those things […] are illegal.”

Mennillo doesn’t think that the same standard is applied for different stores. A pharmacy or book store selling a product with hemp oil, or a book about growing cannabis, that has a logo related to weed, won’t be inspected.

“Theoretically, their mandate is to kind of dissuade you from consuming cannabis,” Mennillo said. “So if you walk into an SQDC and they see you showing any hesitation towards buying cannabis, that's a prompt for them to try to convince you to leave the store.”

“It's just a completely different philosophy here in Quebec, and one of the things that goes with it is our inability to grow our plants,” Mennillo said. “Federally, the government permits up to four plants per person. The idea being that, ‘Hey, if it's legal, you don't have to buy it.’ You might not have the means to buy it. You can just grow it yourself right on your balcony, in your backyard, whatever. And in Quebec, we don't have that.”

Mennillo sees this stigma in Quebec as being a roll-on effect from the racialization of cannabis.

There are currently eight other countries that have legalized recreational cannabis use, including Germany, Mexico and South Africa. It is also legal for recreational use in certain U.S. states, such as Colorado and California.

Despite legalization, Wilson said she still feels self-conscious about smoking weed in certain public spaces because people often give judgmental looks, reflecting the lingering stigmatized attitude towards cannabis use.

Wilson recalled a time at work when she lit a joint during a meeting, where alcohol and cigarettes were common. She was quickly criticized.

“They were like, ‘Lailaah, you're smoking weed in a meeting,’” Wilson said. “It wasn't like I was interrupting the start of the flow of the meeting.”

Wilson was then brought to a meeting with higher-ups where she was reprimanded. She recalled the story as being a testimonial moment, reminding her that cannabis is still not accepted.

Outside an SQDC in Anjou, The Link spoke with cannabis consumers about how legalization changed their lives.

Some consumers told The Link outright that legalization had no effect on their smoking routine. However, car builder Antonio Vittoria expressed a different perspective on legalization.

“[Weed legalization] didn’t change anything, but it kept me safe,” Vittoria said. “I didn’t have to worry about getting arrested or hiding it—which was my main concern.”

Many can feel safer consuming cannabis. According to Statistics Canada, about 29.4 per cent of cannabis users obtain their cannabis from a legal source which is nearly three times higher than before legalization.

Canada’s Department of Justice website highlights this advantage of cannabis legalization with an 85 per cent decrease in the criminalization rate since before the legalization of cannabis.

“You can't just wash away stigma that's been breathing in people’s subconscious for 100 years,” Mennillo said. “This will take a very, very long time to go away.”

This article originally appeared in Volume 45, Issue 4, published October 22, 2024.