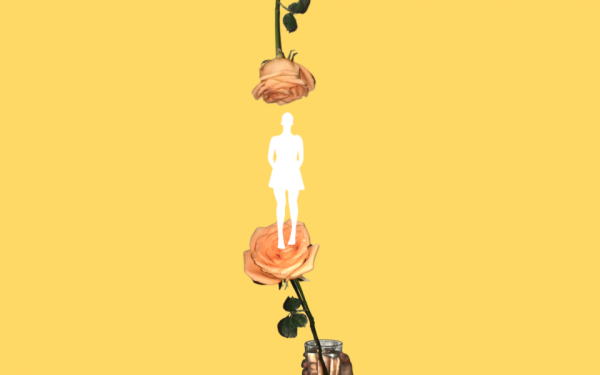

Idolized and controlled: The reality behind K-pop’s shiny surface

Stop placing your K-pop idols on a pedestal

I got into K-pop four years ago, but over time, I’ve distanced myself from the industry.

Nowadays, I occasionally listen to K-pop music and follow idols on Instagram, but I no longer engage with the fandom the way I used to.

K-pop idols may appear cute, funny and shy in front of the camera, but their public personas are often manufactured. Their companies heavily monitor and control their behaviour, whether online or in person. Not to mention, they lack agency over their music and public image.

Through my interactions with other K-pop fans in the past, I’ve noticed them leaving heartfelt birthday messages for their favourite idols. Fans thanking idols for being a source of light and support during tough times is common practice, with some going as far as claiming idols have saved their lives. Fans can also win video calls with idols, which reinforces parasocial relationships and creates the essential illusion that stars genuinely care about individual fans.

It is also strengthened by multiple apps K-pop idols use to “communicate” with their fans—sending messages wishing fans a good day, updating them on their lives, asking if they’ve eaten and telling the fan base how important they are for the idol. Additionally, idols never fail to thank their fandom when winning a prize and proclaim that they are the reason they do what they do. Groups like TOMORROW X TOGETHER even have a song dedicated to their fans.

K-pop relies heavily on feeding the fantasy that there might be a chance for a personal connection with artists. I am reminded of Jean Baudrillard’s theory on hyperreality: the simulation is incredibly immersive, even more so than reality, and we’re loving it. Falling into this simulation is easy for younger minds, but it becomes problematic when this fantasy overshadows reality as we age, clouding our perception of the real world.

The term “idol” itself seems odd, especially considering the Cambridge Dictionary definition: “An idol is a person who is loved, admired, or respected a lot.” In K-pop, an idol’s success is often judged by their perceived perfection in the public eye, which can be unsettling. The illusion is often broken and a scandal erupts if a K-pop idol is seen smoking, dating, wearing revealing clothing (for female idols) or drinking alcohol. These activities, which are often overlooked for Western celebrities, are forbidden in the K-pop realm—forbidden, of course, only in front of the camera.

Last year, idol, fashion designer and professor G-DRAGON was accused of using drugs. The allegations persisted despite his denial, and he had to voluntarily appear at a police station for questioning. G-DRAGON was ultimately exonerated of the charges, highlighting how even unfounded accusations can tarnish an artist’s public image. This incident exemplifies the precarious balance celebrities must maintain, as they often face scrutiny whether or not they are truly at fault.

However, it’s worth remembering that idols are not always as innocent as they may appear. It’s interesting to observe the discrepancy between the punishments idols receive when prosecuted for alleged drug use, as seen in the case of G-DRAGON, and when they misuse their power to sexually abuse women. In 2019, a major scandal erupted in South Korea involving Lee Seung-hyun, a former member of the popular K-pop group BIGBANG. As the CEO of the club Burning Sun, Seung-hyun was implicated in a scandal involving prostitution, drug trafficking and police corruption. Initially sentenced to three years in prison, his sentence was eventually reduced to 18 months.

K-pop fosters parasocial relationships from its roots, allowing fans to grow a disproportionate attachment to idols. Given these incidents, it’s shocking to see that some fans continue to defend such idols and believe their favourites are exceptions to the industry’s patterns of behaviour. This piece is not meant to spoil anyone's enjoyment of K-pop but rather to express that K-pop idols are far from perfect. They are powerful individuals who may use their influence for nefarious purposes.

This article originally appeared in Volume 45, Issue 2, published September 17, 2024.