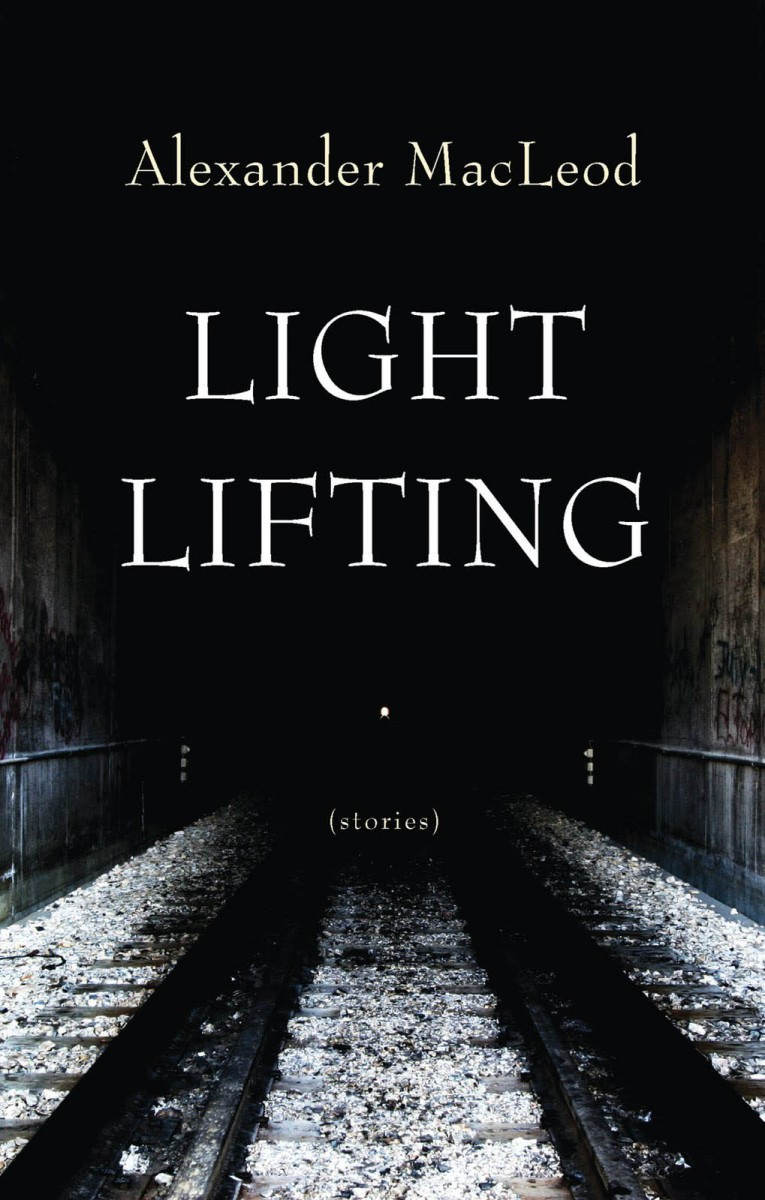

Full Transcript of the Interview With Alexander MacLeod

Alex Manley conducted an email interview with Canadian author Alexander MacLeod for “Short Listing,” published in The Link’s Oct. 19 issue. Here’s the full transcript of that interview, touching on MacLeod’s experiences as both son and father, how being shortlisted for the Scotiabank Giller Prize has changed his life, and the process of writing his debut short story collection, Light Lifting.

The Link: Has being shortlisted affected your day-to-day life much? Do you expect that things will subside at some point—in December, in February, by the time the next Gillers roll around? Or do you not have time to think ahead?

Alexander MacLeod: I would have to say that, yes, the Giller news has affected my life. Before the news came down, we were just planning on nursing the book along, one reader and one copy at a time, and hoping, maybe, for some good ‘word of mouth’ reactions to move it on its way. I think we thought, it might take a few months or even more than a year before people really even knew the book existed. Instead, all of that happened in one day. I got the book on a Saturday evening, I read it for the first time on Sunday, and the announcement was made on Monday morning. We’ve been chasing after it ever since and all the outside attention has definitely changed our routine at home. We’ve managed okay, thanks to the generosity of my wife and our adaptable kids, but it’s a good problem to have and it’s a once-in-a-lifetime thing. I think this will slow down after the 9th, when it’s all over, but up to that day, the day-to-day activities are pretty intense.

Wayne Gretzky’s son Trevor recently committed to playing baseball in college. You, however, followed in your father’s writerly footsteps. You said in a recent interview with the National Post that you never talked to your father about writing, though. Do you think that made it easier for you to grow into your own as a writer?

My parents raised six kids and I think they had a good strategy for dealing with whatever creative endeavours their children sought to pursue. My mom and dad didn’t purposely ignore my writing and they certainly would have helped me out if I had asked, but they also understood and respected how important it was to give me, or the rest of my brothers and my sister, enough room to do our own work in our own ways. There’s a lot of variety in what we’ve produced and I think that comes from letting each person figure out their own relationship with the material they care about most.

Another thing you discussed in the Post interview was that “life” had delayed the release of the book, which is your first. Did the “big hotshot young guy” writer in you worry about the years slipping by or were you confident that your work would find an audience regardless of when it came out?

No, I didn’t worry about that stuff. I’ve had the stories, most of them, with me for many years, and I knew the first ones weren’t going to change too much in the collection. That being said, pulling the book together during this last year was actually a very strange experience because it was like going back in time and introducing one version of myself, the guy who wrote the early stories, to the guy I am now, the person who wrote the most recent pieces. It was weird because each separate story was completely its own project but it was only when they were pushed up against each other that I saw all the common threads flowing between them, currents of concerns that had been there for more than a decade, running under the surface. It was surprising to me to discover that that the book might come together like that, cohere in a way I never expected it would.

The Giller citation for Light Lifting characterized the stories as being very focused on physical sensation. I found that to be almost overwhelmingly the case. Everywhere your characters are grounded in the physical world through struggles of varying degrees of intensity—checking for lice, learning to swim, training to run, cycling for work, lifting light loads of bricks. Was that an intentional choice for the collection or is that something that occurs naturally in your writing?

It wasn’t intentional but I think it’s just the way that I see things. I was interested in looking at different moments of decision or choice and those moments are usually pretty intense on the emotional, intellectual and even physical levels. I wanted the choices to matter in a fairly substantial way so I think that’s why the physical element is there. With the athletes, it’s obvious that every significant action will be expressed physically – that’s the difference between the 3:36 or the 3:39 1500m – but with the young family or the elderly people in the book, I wanted to explore how their lives, and their decisions, are also governed by those sorts of forces. An old lady who refuses to be institutionalized and won’t give up on her house is backing up her emotional desire with a physical action. Every time she goes out to shovel the sidewalk by herself she’s doing and saying something with that movement; same thing for the young couple who have to change stinky diapers or check for lice or take the kid to the hospital. Their love for their children or their love for each other takes on a physical manifestation. We can see and learn something about the full depth of their emotional commitment by monitoring their actions, the way they move through their worlds.

The stories are very Windsor-centered, perhaps nowhere more so than in the final one, “The Number Three,” which does a great job of making something (the history of GM [sic] minivans) that might otherwise seem mundane into a compelling thread that really enriches a story that is essentially about family ties and post-traumatic emotional survival. Since you grew up in Windsor, did you have to do extensive research about all this car manufacturing jargon or was that something that you were to some degree aware of one way or another before you started writing the story?

Better be careful with that question. It’s the Chrysler mini-van we’re talking about, here. (Ha). Details like that matter in a place like Windsor. Yes, I did some research on the generational changes that the Caravan went through from the 80’ to the present, and I was interested in the way they’ve kept re-designing it and re-engineering it to fit a slightly different segment of the market; but I was mostly interested in trying to puzzle through the relationship between the protagonist and this object he’s worked on for so much of his life. Even the names they put on the van felt significant to me: Grand Caravan, Magic Wagon, Voyager, Town and Country. They seemed almost saturated with meaning. I never worked in that plant, but plenty of my friends and relatives did and continue to. My publisher Dan Wells worked in there for seven years, following in the footsteps of his Dad. The place, that plant, and the thing it produces, that van, matter to almost everybody in Windsor and I was trying to think about how we are all connected to this object whether we work on it directly or not. I drive a 2000 Grand Caravan and I sometimes feel weird just sitting inside it because I know exactly where it comes from and I think I probably know quite a few of the people who made this actual vehicle, though no trace of their effort remains.

It’s remarkable the way you manage to balance having seven narrators (well, 5 and 2 non-narrator protagonists) who all sound and feel just the right amount of different from each other and the right amount of similar to each other. How much did you focus on balancing the stories against each other? Did you have to make sure certain aspects of one didn’t bleed into another?

That was almost completely accidental. I didn’t want to tell the same story seven times and I wanted there to be some real variety inside the book, but other than fiddling with the order of the stories, we didn’t really try to set up that ‘similar but different’ feel –it just happened.

This article originally appeared in Volume 31, Issue 10, published October 19, 2010.