Fate, faith and tattooing: How artists from the Maghreb and Iran are reinventing their relationship with tradition

‘Dot by dot like a baby gazelle’ examines decolonization through tattooing and divination

“Growing up, my grandfather in Iran had tattoos all over his body. That was very normalized in my life,” said Mitra Fakhrashrafi, the curator of Dot by dot like a baby gazelle, an ongoing exhibition at La Centrale which hones in on tattooing in Iran and the Maghreb as an entry point to discuss gender, diaspora, and the creation of alternative futures.

The exhibition encompasses a wide range of mediums, including installation, photo, sculpture, and film.

The title of the exhibition comes from a song by Aissa Djarmouni, connecting the act of tattooing to the landscapes of his native Algeria by describing it as done “dot by dot like a baby gazelle grazing in the plains of the Olive river.”

“Growing up Muslim, I was also told by my people that tattooing was forbidden in Islam,” said Fakhrashrafi. “However, history shows, especially in Shiia Islam, the relationship between tattooing and faith is quite ambiguous and there is quite a lot of tattooing that takes place.”

“The entry point is the body itself,” she said. “The artists use their own bodies and think about how the body is perceived to get at these ideas of surveillance and liberation.”

Nowhere in Dot by dot are these ideas as foregrounded as they are in artist Iman Lahroussi’s contribution. Layering Amazigh facial tattoos onto a state portrait of her grandfather, Lahroussi’s Ya Mohamed: Post-Mortem deals with cultural identity through one of the photographs, one of the oldest forms of biometric identification, Fakhrashrafi wrote in her curatorial essay.

On this image of her grandfather, which would have been used to restrict his immigration, Lahroussi superimposes her grandmother’s tattoos. These tattoos, typically signifying strength and the expulsion of evil when apposed onto North African women, subvert the initial intent of the photograph.

“Before we had all the drones and facial recognition that we have now, photographs are what took the face and [turned] it into information,” she said. “And it’s used to decide whether you have access to a place or not on these racialized terms.”

Lahroussi’s grandmother had tattoos on her hands and face, which was very common for women of the time. “But a large part of her generation grew to feel shame around these tattoos because of the stigma surrounding nationalism and these rigid ideas of faith,” said Fakhrashrafi. “They would cover them and not show them and now their grandchildren are the ones that are learning about the colonialism that is still happening and wanting to reclaim these practices.”

This idea, of the body as history, is revisited in Neissani, a combination of a short film and a sculpture by multimedia artist Nazlie Najafi. For the sculpture, the artist has hand-drawn all of her grandfather’s tattoos—flowers, a knight, a couple—onto a statue. In her short film, her grandmother recalls how he came to get them.

"Deciding what goes on your body, deciding what you hold onto, that’s really important,” said Fakhrashrafi.

However, one of the exhibition’s throughlines, reclamation of tradition, is also expressed in its treatment of fate, looking back to practices of the past which have been stamped over by modernity.

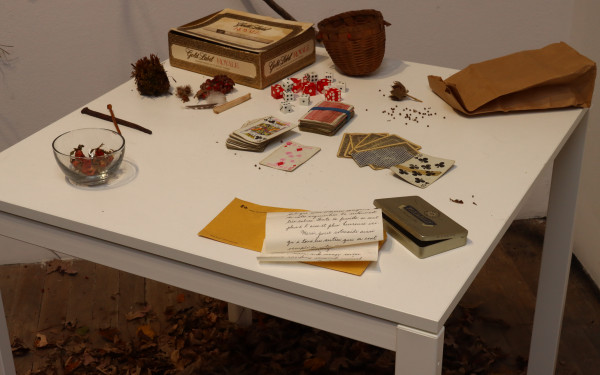

For the exhibition, Mélika Hashemi prepared an interactive installation named Witness (This Could Be Magic.) For this work, Hashemi designed a series of temporary tattoos inspired by Persian fortune telling cards, signing them, and putting them in a gumball machine. The viewer is then invited to “set an intention or ask a question, and whatever they receive is at the random will of the machine but is also predestined,” said Fakhrashrafi.

“Deciding what goes on your body, deciding what you hold onto, that’s really important.” — Mitra Fakhrashrafi

“I always am very excited by Mélika's work because it engages with these ideas of faith and brings them to these places you wouldn’t expect them to be. She’s asking us to see God in the everyday,” she continued.

She further cited digital examples of these kinds of reinterpretations, such as hafizonlove.com, a website which, using the words of renowned oracle and poet Hafiz, issues one of his works at the click of a button, aiming to answer the user’s question.

Also on display at La Centrale is Breaching Towards Other Futures, a performance lecture by Shirin Fahimi and Morehshin Allahyari. The performance, which is broadcast on video, is inspired by Aisha Qandisha, who is “one of the most honoured and fearsome jinn in Islam,” wrote Fahimi and Allahyari. It also features the practice of imn al-raml—which translates to sand science or knowledge—an antediluvian form of soothsaying which, much like tattooing, can be considered illicit within Islam.

In the video, Fahimi and Allahyari sit near a large spread of sand on one of the platforms at the Floating University in Berlin, performing the ceremonies associated with imn al-raml while reciting an essay written for the piece.

When the work was first conceived, in 2018, Fahimi was concerned with the recent Muslim ban in the United States. “So at that point my question was ‘What’s the future of these borders? How will bodies cross?’”

Iman C. Chahine, in her paper “Imn Al-raml: A Case Study in Mathematizing Divination Systems Using Modular Arithmetic,” wrote that this type of divination consists in interpreting the combinations of dots in the sand. Simplified, it’s a binary system—one dot or two dots—then organized in a series of four to form what Chahine calls a root shape. There are four root shapes per chart, meaning that “the total number of possible charts equals 16 × 16 × 16 × 16 or 65,536,” she explained.

“After extracting the 16 shapes, al-darib [the hitter] then examines the patterns of shapes, deciphers the configuration, and eventually gives an answer or forecast for his client,” concludes Chahine.

Read more: Bahay Collective celebrates third anniversary

“City people who couldn't necessarily see the stars would inscribe on the sands and used this practice to answer questions about life and [Fahimi and Allahyari] used this to try to answer questions about justice and liberation,” Fakhrashrafi specified.

Fahimi feels that her work, despite being angled towards the future, is perfectly in line with this history. “Historically, that’s what divination is about. You are in pain. You are in trouble. You ask if there’s a way you can keep on living,” she said.

“Raml is about giving you some options. It's more like, there’s these doors open, but you can take them or close them. My work comes out of the interpretation of these doors.”

Dot by dot like a baby gazelle is at La Centrale Gallerie Powerhouse until April 7, 4296 St. Laurent Blvd.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)