OBORO art center starts the year with two new exhibitions

The projects unite memory, family, and art with a multimedia approach

OBORO, both a media production lab and an exhibitor located on 4001 Berri St., has kicked off the year with the exhibitions Senimikwaldamw8gan – Mémoire de pierre by Mélanie O’Bomsawin, and First Fifth by Roberto Santaguida.

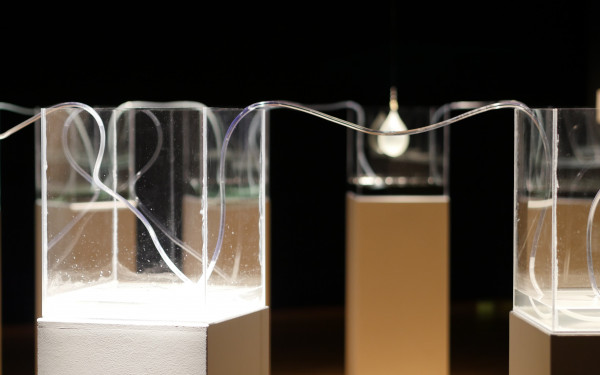

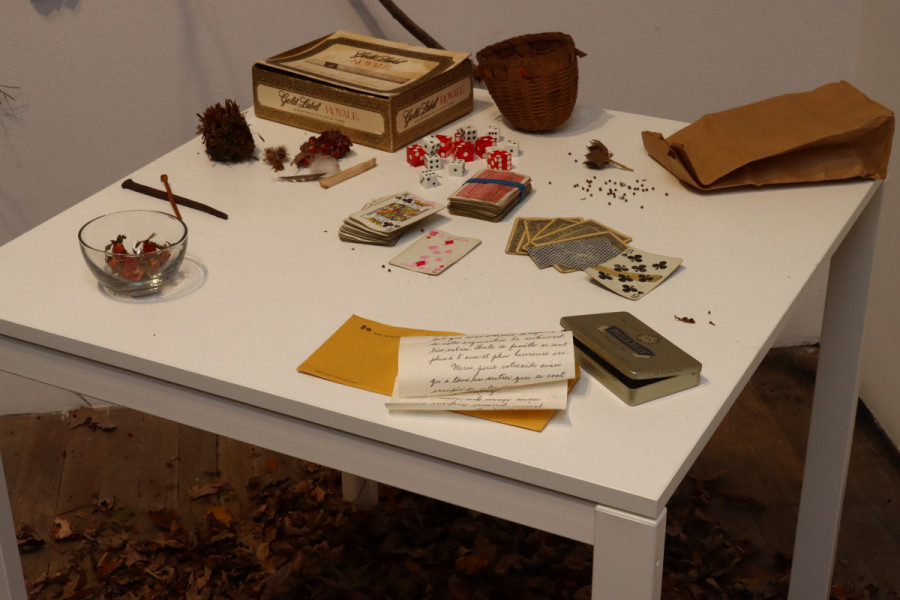

Shown in the Salle Daniel-Dion et Su Schnee, O’Bomsawin’s work features an array of tactile objects, as well as visual displays. There are natural objects like tree branches, leaves, and rocks, and there are digital objects like hard-drives, USB keys, and DVDs. In this way, O’Bomsawin’s art brings together nature and technology. O’Bomsawin’s piece explores what it means to transfer generational knowledge to your children—the future—as well as gaining knowledge from your grandparents—the past—in order to better understand today—the present—and unify time.

“I feel like technology is a powerful tool to create archives, but at the same time, oral history is what made my culture stay alive,” O’Bomsawin said.

She explained that she sees the importance of oral history, theorizing that relying solely on archives to keep Indigenous culture alive would’ve resulted in its death, with priests and other authority figures taking those away.

“At the same time, you have visual support with technology—I can see the face of my great grandfather,” she said, referring to one of the pieces in the exhibition that shows a software recreation of her grandfather’s face. Even now that her project is finished, O’Bomsawin confesses she still questions what the balance would be in her own life between technology and oral culture.

Being both of Québécois and W8banaki origin, O’Bomsawin includes W8banaki symbols in her art. This exhibition contains many of them scattered around—for example, there are rocks placed in almost every corner of the room.

“For us, rocks are our grandfathers, because they were the first on earth and they’ve seen life, and rivers, and everything,” she said.

Another element in her exhibition is the inclusion of two bundles hanging on one of the walls. “Bundles are really important in my culture, they’re small pouches where we put sacred herbs and sacred items that you bear with always. Sometimes it’s not physical; it’s knowledge. I put two pouches for my children,” she explained.

For O’Bomsawin, there were two main inspirations for the exhibition: her desire for her grandfathers to meet and to talk, and to bring generational knowledge to her children.

“I don’t mind if people don’t grasp every little detail that I’ve put,” she said. “I want people to get curious and ask questions and discuss, so we can create education through questions and curiosity.”

“I want people to get curious and ask questions and discuss, so we can create education through questions and curiosity.” — Mélanie O’Bomsawin

Even though they explore them differently, O’Bomsawin and Santaguida’s exhibitions have similar themes such as family and memory. “This was a very fortunate outcome but not necessarily one that was fully anticipated,” said Tamar Tembeck, OBORO’s artistic director. Santaguida’s show, set to be exhibited in the fall of 2020, had to be pushed back because of COVID-19. “Both Melanie and Roberto are video artists first and foremost, there’s a common language on that level,”she said, expanding on the similarities between the artists.

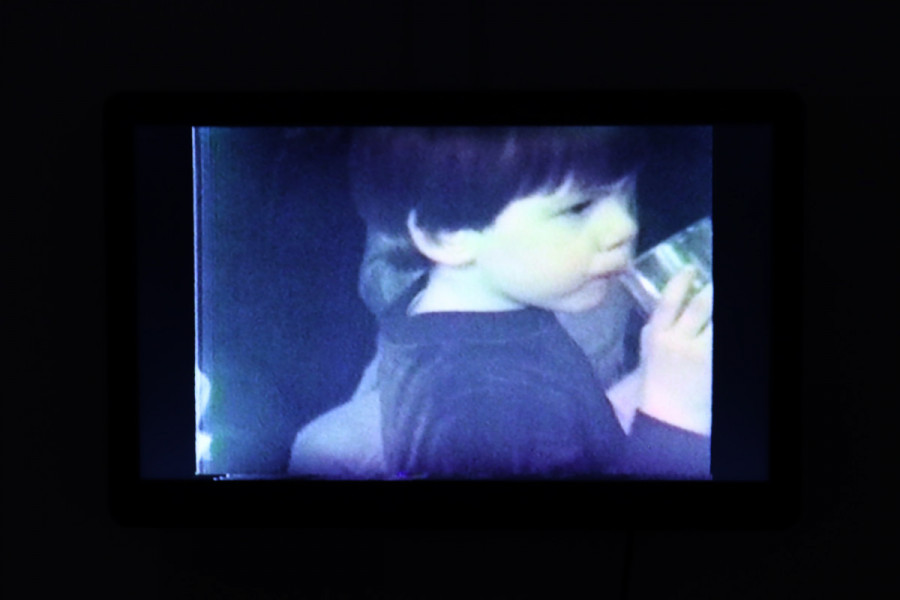

Santaguida’s exhibition doesn’t focus on physical objects as much, rather it focuses on an abstract approach to found footage. The project creates the feeling of visiting a memory through a dream. “[It’s] a disintegration, like scattering the pages of a book you've written, and then settling on that new random order and throwing the rest out,” he said.

Read more: New multiple disciplinary exhibit in downtown Montreal examines our vision of nature

The Petite Salle, where First Fifth is presented, has a dark curtain covering the entrance. In this way, the room is only lit up by the images on the different screens. The screens are continuously playing their respective videos. These videos have been carefully selected by Santaguida over the past five years.

Even if the videos portray very natural and relatable experiences, such as family reunions, Santaguida’s exhibition is hazy and abstract. This might be because of his experience of memory. “There is little separation between my dream life and memories,” he said.

His artistic process behind the exhibition was very long-winded and meticulous. “I spent most of my time accumulating and casting off a long series of short videos until I finally wound up with the specific version on display,” he said. “Right up until a few months ago, I was changing the content of the screens.”

The videos Santaguida used were mostly filmed by family members. “Most of the material I had never seen, but I did remember living through those events,” said Santaguida when discussing the process of finding the footage. “Watching the tapes was an emotional experience—it was difficult to see the effects of time on the people around me.”

Both of the exhibitions were created in collaboration with OBORO and other artist-run centers. “It is a coincidence that they were brought together both with Oboro and other organizations,” said Temback, drawing on the involuntary similarities of both the exhibitions. “It’s a very fortunate outcome when it’s possible to see a project through, from its inception to the point where it can reach the public, but that doesn’t always happen,” she added.

This kind of collaboration is possible because Oboro’s mandate extends over both the production and the presentation of different arts, explained Tembeck.

Both exhibitions are available to visit at no charge until March 5.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)